The historian, political strategist, and objet d’art James Carvell said it sometime in 1992, and ever since it’s become part of American waking consciousness. “It’s the economy, stupid.” The context, you probably remember, involved the presidential campaign of Bill Clinton, a post-Kuwait recessing economy, and the freefalling approval ratings of George H.W. Bush. Those specifics, though, don’t explain why barely a week passes without the phrase dipping in and out of newspapers, cable news shows, and evidently, magazine pieces in 2022. Thirty years later, we’re still saying, “It’s the economy, stupid” because the sentiment taps something at the street-level of how most of us experience most days.

If you’ve been around, you already know: At Common Good, we understand economy not as another convoluted topic for politicians and university profs — “the” economy — but more like a garden, an ecosystem of lives and livelihoods that has as much to do with your corner grocer and what you think about your neighbors as it does Washington D.C. In the garden of economy, no matter the season and state of health, there’s always work to do. Pruning and weeding, watering and draining, toil and pleasure. This shouldn’t surprise you, of course, since the project of humanity started in a garden and the creator hasn’t amended his call to “be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it.”

That’s the problem with Carvell’s maxim, as much as it still clarifies political priorities and voter feelings, it reinforces a false narrative that the economy is something out there for someone to figure out. True, dozens of factors and forces come into play, but when it comes to this economy, you see, we’re doing it. With purchases, yes, and with jobs and time and neighbors and church. And to a certain extent, whether or not the economy flourishes depends on you and on us.

That’s why we’ve created this ranging, aspirational, unperfect list of ideas for a flourishing economy.

Here’s how it’s going to go: We organized these ideas into five categories — foundational ideas, ideas for individuals, churches, businesses, and for the public square. Even with a number like 102, we left out dozens of worthy ideas. We’re not trying to be comprehensive, really, but to contribute to a dynamic conversation about God and his creation, the works of our hands, and the common good. To show you some of the best thinking we can find. To inspire some of the best doing by people like you. And to help us all be obedient to the God who put us in the garden in the first place. So that when we hear, “It’s the economy, stupid,” we’ll remember to get to work.

We Hate to Assume, but …

Everything else you’ll read in the next 28 pages assumes these 12 ‘elements of economic wisdom’

Back in 2013, the Oikonomia Network initiated an effort that led to the development of “12 Elements of Economic Wisdom.” These truisms aren’t plans or promises, but proverbial statements, “generalizations that are broadly applicable, rather than absolute laws for all cases,” not all that unlike what you find in the wisdom literature of the Scriptures. These elements form a foundation on which we built our 102 ideas, and without which our ideas don’t really make sense. Here they are.

Stewardship and flourishing

We were given stewardship over the world so our work would make it flourish for his glory.

1. We have a stewardship responsibility to flourish in our own lives, to help our neighbors flourish as fellow stewards, and to pass on a flourishing economy to future generations.

2. Economies flourish when people have integrity and trust each other.

3. In general, people flourish when they take responsibility for their own economic success by doing work that serves others and makes the world better.

Value creation

Through economic exchange, we work together and create value for one another.

4. Real economic success is about how much value you create, not how much money you make.

5. A productive economy comes from the value-creating work of free and virtuous people.

6. Economies generally flourish when policies and practices reward value creation.

Productivity and opportunity

Economic systems should be grounded in human dignity and moral character.

7. Households, businesses, communities, and nationals should support themselves by producing more than they consume.

8. A productive economy lifts people out of poverty and generally helps people flourish.

9. The most effective way to turn around poverty, economic distress, and injustice is by expanding opportunity for people to develop and deploy their God-given productive potential in communities of exchange, especially through entrepreneurship.

Responsible action

Economic systems should practice and encourage a hopeful realism.

10. Programs aimed at economic problems need a fully rounded understanding of how people flourish.

11. Economic thinking must account for long-term effects and unintended consequences.

12. In general, economies flourish when good will is universal and global, but control is local, and personal knowledge guides decisions.

Ideas for all (foundational thoughts)

1. The Bible gives a seedbed for economic activity.

It takes just about a page — 30 lines, in an average-sized Bible — to get to the biggest, most important statement of economics in all of Scripture. God tells the first humans to “be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground.” We call this the creation mandate, and it shapes everything that comes after it. A fruitful life is what Adam, Eve, and you and your family are called to.

Of course, the first two chapters of Genesis lead us to chapter three: the fall. The introduction of sin in God’s creation does not undo the cultural mandate — but it does change the nature of labor forever and set up the context for all we do.

2. The church’s witness shows a pattern of economic generativity. For example:

The common good is good of a higher order that an individual shares as a member of the community. It is not private good, but it is good for the individual. (Thomas Aquinas)

For it is necessary for the preservation of human society that each should possess what is his own; that some should acquire property by purchase, that to others it should come by hereditary right, to others by the title of presentation, that each should increase his portion in proportion to his diligence, or bodily strength, or other qualifications. In fine, political government requires, that each should enjoy what belongs to him. (John Calvin)

God has always wanted the vulnerable in society to be cared for. He never intended for them to languish in poverty, abuse, slavery, homelessness, or other types of devastation. When we care for individuals who are trapped in these ways, when we show them love and help them move toward freedom and wholeness, we participate in bringing a little part of God’s Kingdom back into alignment with his

greater plan. (John M. Perkins)

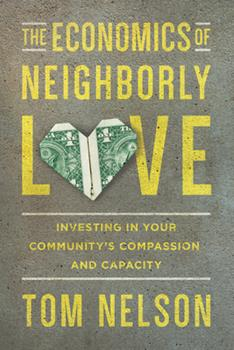

3. All social activity should relate to the common good.

The apostle Paul calls Christ-followers and the local church to seek the flourishing of all people. In penning his Spirit-inspired letter to the Galatians, Paul writes, “So then, as we have opportunity, let us do good to everyone, and especially to those who are of the household of faith” (Gal 6:10). One of the most important places where we seek the common good is in our daily work. The prophet Jeremiah called the exiles in Babylon to care for their pagan neighborhood. One of the main ways God’s covenant people were to seek the shalom or the flourishing of Babylon was to engage in economic activity. Creating economic value and sharing economic value with the Babylonian neighborhood was a vital component of nurturing shalom. As Jeremiah exhorts the Jewish exiles to seek the welfare of the city of their captivity, he speaks not only in familial terms but also in economic terms, calling them to build homes and plant gardens (Jer 29:5‑7). In the interconnected economic web of a flourishing Babylon, God’s covenant people would experience their own economic flourishing. In seeking the common good of the city of Babylon, they too would experience the common good and common goods of mutual economic collaboration. (Tom Nelson, The Economics of Neighborly Love)

4. The cultural mandate is about more than babies.

A little more on Genesis. “Be fruitful and increase in number, fill the earth and subdue it.” We tend to think about the cultural mandate as a case for baby-having. It is. But it also means work, innovation, and industry — all of which are inextricably tied to what it means to be fruitful. To adapt Richard Mouw, the world starts in a garden and then becomes a city in the end. Somehow, we have to get there. It turns out, you and all of us are the how.

5. A flourishing economy requires virtuous actors.

Adam Smith knew this. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, the long-winded and more Scottish title for Smith’s Wealth of Nations came out in an already consequential year: 1776. This is the book that lays out a framework and case for what could become the political economy of the burgeoning United States. What’s instructive, is that Smith’s other significant book — The Theory of Moral Sentiments — came out almost 20 years before. Though the case isn’t stated explicitly, the timing nods to what a lot of us already know: For an economy to work, for a society to work, the people in the system have to be pursuing the good and virtuous in the first place.

6. Pastors and churches are means of grace and good for their cities.

Your church is where your church is for the good of the city. This is partly why church doesn’t always work online, at least not long term. Because your church isn’t everywhere, and to attempt to be so is to have a church no where.

When you see the church as a means of grace to the city, you will start to shift some tendencies to view some of the particulars of our contexts as obstacles to overcome to opportunities to be an embodiment of the kingdom. To being a means of good not for a generic world but for your city, neighborhood, and street.

7. Institutions matter (government, finance, and family).

Although the scope of government involvement in economics is debated, there is consensus that government has a role to play in a vibrant economy. Governments in a modern economy are actively involved in a host of ways. In a broken world filled with broken people, economic actors need rules and boundaries for economic exchange. Fair and just laws enforced consistently are crucial. … Financial institutions also play a vital role in facilitating well functioning capital markets. … Within the vast financial service industry, a wide variety of financial products have been created that make possible a wide diversification of investments to both individual and institutional investors. The institution of the family also plays a vital role in economic flourishing. In many ways the family is the most basic economic unit in the economy. We’ve already seen that our English word economics comes from a Greek word oikonomia, which connotes the idea of household or family stewardship. There is a seamless, interdependent relationship between family life, the workplace, and the broader economy. In a real sense, as the family unit flourishes, the broader economy flourishes. The family’s procreativity provides the labor force for the economy. Much of the intellectual and social capital the economy depends on finds its source in the dynamic and nourishing womb of family life. … The institutions of government, finance, family, and education all play an indispensable role in a flourishing modern economy. (Tom Nelson, The Economics of Neighborly Love)

8. Jesus embedded economic activity in the Great Commission.

In Matthew 28, Jesus makes maybe his most famous statement: “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you. And surely I am with you always, to the very end of the age.” The Great Commission. The great part of the commission is its clarity on evangelism. But what we often miss is that in “teaching them to obey everything [Jesus has] commanded” Jesus embeds the seeds of economic wisdom and generativity. Think of the Sermon the Mount (especially, 6:1-4, 7:19-24, 7:24-29).

9. Lady Wisdom is an entrepreneur.

As scholar Hannah Stolze has written in these pages, “there is a tension between the promises of wisdom literature — the books of Job, Psalms, Proverbs, and Ecclesiastes, in the Bible — and the reality of the marketplace.” The tension is that we almost always think of wisdom as ethereal, immaterial. The marketplace, though, that’s made of brick and carpet and website and includes truisms like “it’s just business.”

Yet when we encounter the personification of wisdom in the Bible, where do we find her? Like Stolze points out, wisdom is not on a throne or a cloud or even in a temple. “When Proverbs closes in a 21-verse acrostic that sums up the book, Wisdom is found caring for family, leading a company, and, yes, trading in the marketplace.” For us, this has to rewrite the rules of “just business.” Because wisdom is worth far more than great riches, more than profitability, King Solomon tells us. And yet wisdom seems not to be an ascetic, and her effects aren’t contradictory to profitablity. We read in Proverbs 8 that “the way of righteousness and the path of justice to bestow a rich inheritance” on those who love wisdom.

10. Economic flourishing isn’t the most important thing.

In Genesis we are reminded that we were created with community in mind. We were created to flourish, to be fruitful, to add value to others in the world. We also see wealth creation as a good thing, because through it, we reflect our created nature and have an increased capacity to love our neighbor. Indeed, material well-being is an important part of overall biblical flourishing — strength and fertility are improved by increasing productivity. Productivity, after all, is the application of human creativity. Capital isn’t only cash, it’s human. And human capital is the most important kind of capital. But there’s more to the story, and that’s flourishing people. We don’t want to split hairs here, but God is honored by poor communities living in faithfulness and obedience, in prayers and fasting, just like he is in their material blessing. The point, remember, is a people set apart for God, who welcome the coming kingdom. (Tom Nelson, The Economics of Neighborly Love)

That’s 10 — look for the other 92 in your print issue of Common Good.