Donne saw not an iconic approach to God in art but a metaphorical one, an approach he mirrored to describe God, who he believed to be unrepresentable.

ANNUNCIATION

By John Donne

Salvation to all that will is nigh;

That all, which always is all everywhere,

Which cannot sin and yet all sins must bear,

Which cannot die, yet cannot choose but die,

Lo, faithful Virgin, yields Himself to lie

In prison in thy womb; and though He there

Can take no sin, nor thou give, yet He’will wear,

Taken from thence, flesh, which death’s force may try.

Ere by the spheres time was created, thou

Wast in His mind, who is thy son and brother,

Whom thou conceiv’st, conceived; yea, thou art now

Thy Maker’s maker and thy Father’s mother,

Thou’hast light in dark; and shut’st in little room,

Immensity, cloistered in thy dear womb.

Sonnet 2

Sonnet 2

from “La Corona”

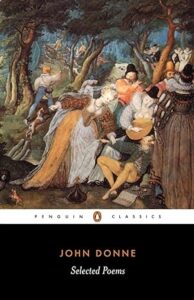

Selected Poems of John Donne

Edited by Ilona Bell

(Penguin, 2006)

In the four centuries since he wrote and preached, he’s regularly counted among the great writers in the English language, his Devotions a canonical “great book,” and among Christians he holds the status of patron saint of creativity. Still, you’d be hard-pressed to argue he isn’t having a moment. A couple of years ago, a new biography of Donne — Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne — presented a paced-up and engaging perspective on Donne, and it received wide critical celebration. When the paperback edition landed late last year, the book received a whole new round of excitement. The conversation around Donne has only picked up, and it’s time for us to talk about it.

For the 400th Anniversary of John Donne’s Devotions, Philip Yancey Rewrote the Book

The Devotions of John Donne are a classic, generally considered one of the greatest English works of all time. Yet the text remains firmly situated in the Elizabethan world. Which is what one of America’s favorite writers intends to remedy.

It’s the 400th anniversary of Donne’s Devotions. But the date isn’t the only thing that makes revisiting Donne’s work worthwhile. For this reason, it took Philip Yancey “no time at all to be enraptured by the book.” But when he “started giving it to people, [he] couldn’t get them to read it.” So Yancey, the author of several books, such as What’s So Amazing About Grace and Where the Light Fell with a bewildering 15 million books in print, had an idea to update Donne’s great work. And finally, during the pandemic, he found his opportunity. This spring, Yancey published Undone: A Modern Rendering of John Donne’s Devotions. After all, the full title, which we rarely see, is Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions and Death’s Duel. In such emergent occasions, is when Yancey says the book is needed most. Donne writes to a context we’ll understand, if only we understand the language.

You make the point that the seeming chaos of our current moment connects to Donne’s life?

Donne had a lot of pain and disruption in his life. He finally settled down, his wife had died, his children were leaving the nest, and now he gets this wonderful job as the dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral at a time when they really needed a spokesperson to represent them to God and represent God to London. Instead, he ends up on a sick bed, convinced that he’s dying of bubonic plague. All those questions of unfairness and randomness and cruelty and guilt and fear — all those things that we work through when suffering — came zooming in on him in a very personal and urgent way. And like a good writer, John Donne works those things out in writing. It’s quite an extraordinary feat: On his sickbed, he didn’t have access to the Bible, from what I understand, certainly not to his library, yet he created a masterpiece of literature that has never been out of print for four centuries.

Why does Devotions need to be more accessible?

There are parts of it that are just way too weird and dated. The grammar, the syntax is so different. This was in the day of Shakespeare and King James I. Shakespeare is certainly performed now in the original language, but not that many people pick up a play and read it. King James Bibles are still sold, but I’m not sure how many of them are read. We keep coming up with new ways to make the Bible more accessible. And so, with fear and trembling, that’s what I wanted to do for John Donne.

You were looking to uncover the elements less bound by time?

It’s a funny thing that the stuff that we think is hard science, irrefutable science — the laws of science seem permanent — but you go back to Donne’s day, and all the science he talks about is just laughable now. For example, the way they treated people in medicine with purgings and bloodlettings, leeches and pigeons. Yet the existential wrestling with God is as contemporary as anything coming out in the middle of a pandemic.

It does seem like the storytellers, the artists, often hold up better over time.

I haven’t met that many people who have become Jesus followers because they lost an argument. But I have met people for whom C.S. Lewis or George McDonald opened up a pathway to faith. I recently read this wonderful new book by Christian Wiman, Zero at the Bone. It’s profound. And it is perfect for a secular, doubting audience because he doesn’t try to talk them into something. By being totally transparent about his own life, he awakens in them longings and questions about which our faith has something to say. I’ve heard Wiman do interviews on NPR and various places, and you can’t dismiss him because he’s a great writer and poet, and he is living with the stuff that our culture is so bad at dealing with — terminal cancer. He does it faithfully and honestly, and you have to take him seriously. I think that’s the genius of John Donne, too. Because, as he said, he was “a man who has known affliction.”

In Undone, what was the nature of the work you did?

Primarily that was a matter of trimming these 200-word sentences. I ruthlessly chopped out stuff that was irrelevant, especially all the weird medicine and science. I probably cut at least a third of the content. I tried as much as possible to keep the verbal music, Donne’s music. I just streamlined it a bit along the line of what Eugene Peterson or Kenneth Taylor did with the Bible, although I was cutting things out in a way they did not. My goal was simply to make its meaning clear.

To what extent is this a book that you edited and to what extent is it a book you wrote?

I contributed seven chapters of background on Donne and his book. But I didn’t write or rewrite John Donne. I may have added a phrase here or there as a transition or clarification, or tweaked the images a bit if they were not self-explanatory. Mainly, I tried to clarify and edit so that more readers can enjoy this classic of theology and literature.

This conversation was edited for clarity and length.

Reading Donne

How John Donne Looked at God and Art

A new scholarly book explores the famous poet’s writing as and about art.

Unless you’re intensely interested in scholarly discussions of the 17th-century poet John Donne, you may not know. But there exists in academic circles a good bit of work around Donne and art. In a new book, Kirsten Stirling, who teaches at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland, suggests that Donne’s approach to art emerged from his theological vision of God. She writes, “Donne’s use of visual art goes beyond the reformers’ debates about images in worship and can be traced to pre-Reformation theological treatises where the metaphor of a painting or a sculpture is employed to illustrate the nature of God or the relationship between human and divine.”

According to Stirling in Picturing Divinity In John Donne’s Writings, Donne saw not an iconic approach to God in art but a metaphorical one, an approach he mirrored to describe God, who he believed to be unrepresentable.

That’s a little complex. Here’s how it played out: To the left is a representative painting from Donne’s era and one of his sonnets. They’re both addressing the annunciation of Christ from Luke 1:26–38. The passage below from Stirling’s Picturing Divinity explains what Donne is doing in his poem.

In the Annunciation sonnet standard theological paradoxes are used to describe Mary’s divine motherhood and relationship to Christ: “Whom thou conceiust, Conceiud; yea thou art now / Thy Makers Maker, and thy fathers Mother.” Echoing the iconography of the painted tradition, the whole sonnet is framed with metaphors of enclosure, of prison and cloister, describing the incomprehensible moment of the Incarnation of the divine in human flesh.

In a 1470 Annunciation by Piero della Francesca, for example, archangel and virgin confront each other within an elaborate structure of columns and arches; it is only by reconstructing the geometry of the scene with the “intellectual eye” that the viewer realizes that in three dimensions one column would logically be placed directly between Gabriel and Mary, obscuring their view of each other. This play with the visible and the invisible points towards the essential and unrepresentable object of every Annunciation — the figure of Christ. Arasse indeed proposes that the painting identified by Erwin Panofsky as the first to employ a single vanishing point — a 1344 Annunciation by Ambrogio Lorenzetti – is already using perspective in order to establish a “real,” human, space in contrast to an “unreal” divine space representing the arrival of the angel. Such a paradoxal geometry, Arasse argues, is fundamental to the painterly representation of the meeting of two incompatible, incongruous spaces in one.

Donne’s impossible “appeals to visualization” in “La Corona” function in a similar way, inviting the reader to construct an imagined space, or picture, but at the same time using paradox to complicate any kind of visualization. In the second sonnet of “La Corona,” the phrase described by Gilman as a “chiaroscuro detail” is part of Donne’s central spatial description of the fundamental paradox of the incarnation: “Thou hast Light in darke; and shuttst in little roome, / Immensitye cloystred in thy deare wombe.”