Readers of Jane Austen will recall the grasping, comedic, and in-possession-of-a-parsonage-of-no-mean-size Mr. Collins. Maybe you have stayed in one of the many parsonages converted into a bed and breakfast. Maybe you think of a dilapidated Victorian like the one George Bailey breaks the window of in It’s a Wonderful Life.

Maybe the word elicits nothing at all. Whether you call it a manse, a rectory, a vicarage, a clergy house, or a parsonage, a definition is in order (and perhaps a defense as well). At its simplest, a parsonage is a house that a church provides for a pastor. For a large portion of English and American history, they formed part of our cultural and literal landscape. Now they’re disappearing.

A church may pay part, or even all, of a pastor’s compensation through this in-kind housing, which is excluded from the pastor’s income relative to tax purposes. Some people incorrectly think parsonages a tax-free benefit, but that’s not exactly true. In this country, clergy hold a unique dual tax status with the IRS: They are both W-2 employees and also considered self-employed, which functionally means pastors must pay their own Social Security and Medicaid taxes. While there is no income tax paid on parsonages, pastors do pay a certain percentage on their housing benefits.

At one time, parsonages were not just common, they were culturally significant. Ralph Waldo Emerson and Nathaniel Hawthorne both lived in a manse for a time, the same one, in fact. Henry David Thoreau planted a garden there to celebrate the Hawthornes’ wedding. Presidents Grover Cleveland and Woodrow Wilson were born in a manse.

Parsonages once captured public imagination. The early 20th-century New York Times reports all sorts of happenings. A minister once shot a seven-point deer in his parsonage dining room. Another reportedly fought a duel on parsonage property. A soldier even sent a captured silverware set purportedly belonging to Adolf Hitler to his wife, who was staying with her father in a parsonage.

Another Times article, from March 10, 1901, reprinted from Longman’s Magazine, describes the parsonage study, a romantic, traditional picture:

Its atmosphere is heavy with the many sermons which have been composed in it. On entering, one is reminded of a three-decker [triplex apartment]: partly by the long shelves full of clerical literature, partly with an odd incongruity of boots and shoes. Should the living be in the patronage of the college the study has almost become a library, and is of fit dimensions to hold a good many volumes. Otherwise it is often littered with fishing rods and gun cases, while in one corner are axes and golf clubs, landing nets and walking sticks, piles of The Field and stacks of The Guardian. Letters and papers are laid on every table, pipes, novels—perhaps they are commentaries—and account books jostle each other on the sofa and chairs. The parson’s wife has given up tidying the room in despair, and the parson is proportionately happier. He can tell amid his orderly untidiness where every paper and book is, though the place seems a hopeless chaos to others. Parochial visitors are shown in here, and the walls have listened to much village gossip and not a few tragedies.

Leisure and scholarship, domesticity and vocation, a homey and yet public space. Amid the smell of leather, tobacco, and old books, the portrait of the parsonage presents several juxtapositions. The pastor who works here, lives here. He is a naturalist and a supernaturalist, task-oriented and people-oriented, accountant, counselor, confidant, and preacher.

While many of these contrasting traits likely still describe many solo pastors, and perhaps especially many rural pastors, too, the reporting reflects what the public found interesting: pastors and where they lived. Parsonages were once common enough to have a place in cultural consciousness and mysterious enough to inspire coverage. Today, it’s difficult to imagine parsonage modifying clickbait.

In Decline but Not Obsolete

Anecdotal evidence from pastors, from the numerous options for bed-and-breakfast stays in converted parsonages (really, just Google “parsonage bed and breakfast”), and from historical archives remembering demolished parsonages, like that at Rollins College just outside of Orlando, Florida, points to a significant decline in parsonage use. National, cross-denominational, empirical evidence is harder to come by.

One 2016 study published in the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion suggests that while 61 percent of U.S. clergy lived in parsonages in 1976, only 14 percent did in 2013. Compared to other traditions, Roman Catholic priests (and seminarians) are more likely to live in church-provided housing; the same study suggested that 44 percent did in 2013. Historically, several Roman Catholic priests lived together, though that is not always the case now.

More recent Current Population Survey data suggest that around six percent of all U.S. clergy live in parsonages. In rural settings, the number is closer to 17 percent. The Siburt Institute’s 2024 national survey reports that just over 10 percent of full-time Church of Christ ministers live in a parsonage. (It’s important to note these figures do not reflect how many churches own parsonages; they only speak to how many pastors live in parsonages.)

Numerous factors likely contribute to the shift away from parsonages, including the desire to own a home, but one economic factor stands out: the Internal Revenue Code. Before 1954, only clergy who lived in parsonages were eligible for an income tax exclusion. Legislative reports explain that Congress changed the law in 1954 to end preferential treatment for clergy who received a parsonage over clergy who did not. In other words, pre-1954 tax law incentivized parsonage living and effectively penalized non-parsonage living. The IRC of 1954 expanded this housing allowance to all clergy, whether they rented, owned, or lived in a parsonage.

Shortly after the law change, Gene Lund assessed the state of parsonage living in a 1960 article for Christianity Today. While lamenting the perceived decrease in scholarship and increase in busyness and worldliness of the 1960 parsonage, Lund claims, “If the parsonage can continue to be what it often has been, a home of noble ideals and genuine human joys, a bulwark of spiritual and intellectual strength, purposeful and devoted to the best for both God and man, then we can anticipate even greater contributions from such a source.” More recently in the Jesuit magazine America, Joe Laramie, S.J., argued for a revitalization of the American Catholic rectory in an article called “Where does Father live?” Despite its problems — and even after the law allowed for a parsonage or a housing allowance — some clergy still consider parsonages worthwhile.

On one hand, declining parsonage use is a positive outcome, as, given the flexibility in tax treatment, more pastors have been given the choice to secure their own housing. Lawmakers’ intent has been satisfied. Pastors and churches possess greater freedom to choose what makes sense in specific situations. But what if we’ve overcorrected?

Although the idea of a parsonage predates the American Revolution, antiquated need not mean obsolete, and none of my other previously imagined descriptors necessarily apply. C.S. Lewis famously warned of “chronological snobbery.” In Surprised by Joy, he defined chronological snobbery as:

the uncritical acceptance of the intellectual climate common to our own age and the assumption that whatever has gone out of date is on that account discredited. You must find why it went out of date. Was it ever refuted (and if so by whom, where, and how conclusively) or did it merely die away as fashions do? If the latter, this tells us nothing about its truth or falsehood. … From seeing this, one passes to the realization that our own age is also “a period,” and certainly has, like all periods, its own characteristic illusions. They are likeliest to lurk in those widespread assumptions which are so ingrained in the age that no one dares to attack or feels it necessary to defend them.

Although Lewis was speaking of weightier matters, his reasoning applies. Just because parsonages feel passé doesn’t mean that they are. Dwindling parsonage use does not mean a parsonage is never the right answer. The trendline provides general information, but it certainly does not dictate what a particular pastor in a particular church ought to do — there might be good reasons to buck the trend. Rick Van Giesen, benefits officer for the Global Methodist Church, still believes case-by-case decisions are best.

“There is no hard and fast rule,” Van Giesen told me. “Each situation is different. Each appointment requires a great deal of dialogue and flexibility for a pleasant outcome.” While parsonages are hardly as common as they once were, they are still a viable if not extremely useful choice.

What Makes a House Worth Having?

While a pastor and church consider their particular facts and circumstances — should they buy or sell a parsonage? — one element of decision-making reality impedes the process. Old decisions have inertia. As Samuel Johnson quipped, “to do nothing is in every man’s power.”

Research shows that decision-makers consistently prefer the status quo, even when controlling for future uncertainty, according to a study in status-quo bias by William Samuelson and Richard Zeckhauser at Boston University and Harvard University, respectively.

In the case that a church does not have a parsonage, there’s often little impetus to consider an alternative. In the case of a church owning a parsonage, the “endowment effect” predisposes a church toward the status quo. And sticking with the status quo, as Samuelson and Zeckhauser observe, also gives the illusion of control. Although the man who always goes to bed at 10 p.m. may freely make the same choice when his house is on fire, we should not regard him as wise.

Homeownership: How Important Is It Anyway?

Given the decrease in parsonage use, the disadvantages are likely obvious: Pastors prefer to own their homes; parsonages may signal a pastor’s short tenure; parsonages blur interpersonal boundaries; pastors want to build equity; pastors need a place to live in retirement; a house is a good investment. But I’d like to make the case for the parsonage’s continued viability.

A frequent objection to parsonage living is financial. Although common wisdom assures us that “owning a home can be a powerful way to build wealth,” homeownership can actually make for a poor investment, and renting is often a better financial decision than homeownership. Consider the tellingly titled journal article by Timothy J. Corriero and Andrew S. Leonard for the Association for Financial Counseling and Planning Education: “Is Buying a House a Good Investment? [Not compared to buying stocks… but that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do it].” We tend to discount the costs of homeownership in buying and selling, making improvements, and performing necessary repairs. Conventional thinking says that renting is just throwing money away, but renters aren’t liable for maintenance or catastrophic losses. Rent is the most money you’ll pay each month; a mortgage is the least you’ll pay every month. Last year, my wife and I spent $7,000 replacing some exterior doors. In the process, we found wood rot and hidden, poorly repaired termite damage that cost an additional $6,600. Spreading that cost over a year would mean that we paid an extra $1,100 per month on our mortgage, about half of which was completely unexpected.

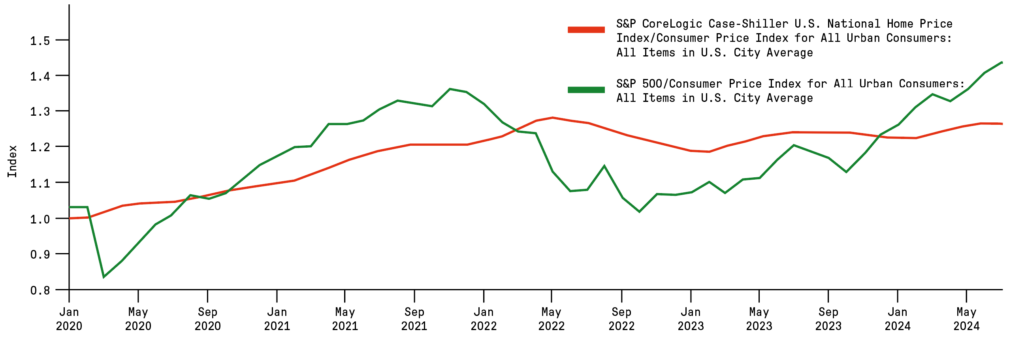

Historically, housing appreciation has just slightly beaten inflation. It’s easy to track how much a home appreciates over time; it’s more difficult to account for inflation (meaning that the house is worth more but in less valuable dollars) and to compare how alternative investments would have fared. Even with the rapid increase in house prices since December 2019, the S&P 500 still outperformed (despite some short-term back and forth.)

The graph below represents the running cumulative gain for both from December 2019. The data are adjusted for inflation and scaled to 100 to make calculating percentage change easy. For example, buying an average house in December 2019 and selling in September 2021 corresponds to a 20 percent return, accounting for inflation.

On average, a house bought in December 2019 for $200,000 would be worth a little under $300,000 as of August 2024, accounting for inflation. In contrast, $200,000 invested in the S&P 500 in December 2019 would be worth a little over $400,000 as of August 2024, accounting for inflation. Over longer time horizons, stocks outperform house appreciation by even greater margins.

This means, from either a pastor’s or a church’s perspective, the primary benefit of owning a parsonage is not financial.

Overall, S&P 500 Investment growth outperformed that of home values from December 2019

But aren’t there tax benefits to homeownership? Yes, but the larger standard deduction often eliminates the usefulness of the mortgage interest deduction, which requires itemizing. And don’t forget about property taxes. Typically, U.S. churches do not pay property taxes on parsonages. Pastors who own their homes do. (Regardless of federal tax treatment, the homeowning pastor must still pay property tax, which in some states approaches $10,000 annually.)

But what about building equity?

Equity, the difference between market value and what is owed on the home, is a relatively illiquid form of savings that generates paltry returns (slightly outpacing inflation). Holding equity means a homeowner is giving up better returns elsewhere. A person would often be much better off investing a down payment instead of using it as a down payment. If $100,000 were not tied up in a home, it could easily earn $4,000 per year in a high-yield savings account. Even if an investor picked the worst day of the year to invest $10,000 in the S&P 500 each year from 2004 to 2023, the average total annual return would have been 10.78 percent. $200,000 would have grown to $640,469. Some online tools like the New York Times’ handy rent-or-buy calculator offers a sense of the financial tradeoffs, including the opportunity cost of a down payment or equity.

Why should equity be the preferred way to save? While the stock market is volatile, especially over short periods, its average annual return is around 10 percent. Past performance does not guarantee future results, certainly, but why would owning a house suddenly become a winning investment?

Of course, pastors need a place to live in retirement, but if a house isn’t a great investment, why treat it like one? A paid-off mortgage can be more than offset by investing regular 403(b)(9) contributions. Contributions are pre-tax (including SECA), and withdrawals can be used tax-free for housing costs in retirement.

Considering investments, Nobel laureate and economist Robert Shiller told Money Magazine that buying a house is more a “consumption choice” than an investment:

Do you really want to buy a house? It’s sort of like having a baby: you’re going to be working, you’re going to be worrying about this house. It’s going to break down, you’re going to get termites, you’re going to have a snowstorm and have to get the roof shoveled, all these things. And then on top of that, it keeps needing painting and maintenance, and it’s a headache.

Would pastors make the same choice if they were thinking about homeownership as a decision between consuming and investing?

How Are We Feeling Now?

While homeownership, surprisingly, may not be the best financial decision, other factors besides finances matter. Some people enjoy house projects, for instance, and for many, homeownership promotes rootedness, connection with neighbors, and a sense of community — an emotional value.

Having spent countless days off working on my home, I can safely say I’d much rather use my time elsewhere. Maintenance means I’m not spending time with my kids, I’m not writing, I’m not pastoring. The opportunity cost — the value of the next best thing I could be doing — of home maintenance is high.

Can we acknowledge that pastoring is stressful and homeownership is burdensome? Instead, for a moment, imagine living in a house that would not be sold or rented away from you, where the lawn is cared for, where unexpected expenses don’t happen, and upkeep is taken care of. Couldn’t it be possible that removing that weight could make for more margin and a better pastor?

Consider the many decisions that homeownership requires, even for a small repair: What should I do about a broken outlet? Does it need to be fixed? Do I know what the problem is? Is it a fire hazard? Do I know how to fix it? Do I have the right tools? Do I have time to fix it? Who will I call if I don’t do it myself? How much will it cost? Will the person do a good job? Is it worthwhile to pay someone to fix it? Do I need to be home while the repair is completed?

Numerous studies explore the problem of decision fatigue: Making many decisions means making poorer decisions. Evan Polman and Kathleen D. Vohs cite several examples in a journal article on decision fatigue. Parole judges were more likely to grant parole in the morning, before many other decisions were made; physicians were more likely to prescribe antibiotics (when they shouldn’t) after working several hours; schoolchildren performed worse on tests given later in the day.

We can easily dismiss decision fatigue arising from home ownership because many of the decisions are small. Discerning their cumulative effect is more challenging. We don’t readily reflect on how the cascading decisions from something as simple as an electrical outlet repair affects that counseling appointment. Steve Jobs, among others, famously combatted decision fatigue by wearing the same clothes every day. What if pastors were as ruthless in eliminating decision fatigue for the good of their churches and for the sake of the gospel? What if churches, recognizing the weight that pastors carry (Rom 12:8), desiring the best possible decisions in leadership meetings and spiritual direction, intentionally fostered pastors’ diligence in leading by removing the burden of homeownership?

Public (and Private) Space?

Some reject parsonages because of concerns about work-life balance. But parsonages can be a relief, not a prison. I have occasionally worked in the yard on off-weekends, which could be awkward if I lived right next to the church. But parsonages need not be on church property (just check state law).

Yes, ambiguity, deferred maintenance, and unhealthy boundaries quickly erode trust between a pastor and a church. One pastor relayed this story: “A pastor’s wife, shortly after moving into the parsonage, came out of the shower in her towel to find a strange man sitting in the living room, apparently looking to have coffee with the pastor, unscheduled. She screamed. He, embarrassed, hurried out mumbling ‘maybe you should lock your door.’”

Unhealthy church dynamics certainly complicate housing. Pastor Colin Vander Ploeg recounts the disadvantages of “having your family’s home overseen by a committee and scrutinized by a few too many congregants who seem to feel the house is theirs. As well meaning as people believed they were, they said things like ‘I see you left a light on in the house all last night. The church pays the electric bill you know.’ Or ‘Oh you have an outlet not working? Don’t touch it. We will bring that up at the next committee meeting and decide what to do.’”

Surely — hopefully — such occurrences are rare, but an early, honest conversation beats an unwelcome surprise. Again, an off-site parsonage would also help alleviate privacy concerns. I wouldn’t live in a parsonage if I didn’t trust the church’s decision-making mechanisms, but I also wouldn’t pastor there in the first place. Clear parsonage policies and clear boundaries matter.

A Disciple’s Case for a Parsonage

As far as I know, Robert Shiller was not intending to paraphrase Jesus’ words about treasure (Matt 6:19–21). And I am (for now, at least) a homeowner. If my habits do shape my love, the time and money I spend on my house directs my attention and affection toward my house. When I do house projects, I come to love my house more deeply. Little projects ignite my passion for bigger projects. Even the enormous hassle and expense of getting the rot and termite damage repaired nearly inspired a kitchen renovation. Why does it bother me so much when my kids rip a towel bar from the bathroom wall? Yes, I’ve told them not to do pull-ups on it, and yes, I’ll have to fix it or pay for it to be fixed, but isn’t the underlying reason that I love my house? Counterintuitively, the time or money invested in the repair amplifies my love for it.

Have I bought into the American Dream, a characteristic illusion of our age, because I own a house? Do I really believe that the good life means homeownership? Is homeownership a necessary component of neighborliness or community? To what extent have I overestimated the stability homeownership provides? Could not owning a home reduce stress and decision fatigue so that I have more margin elsewhere? Could it be possible that parsonage living might help me relocate my treasure to its rightful place and long for a better, heavenly country?

Parsonages are hardly panaceas. There’s plenty of room for pastors to make their own choices, given their particular circumstances. Is it possible that my strategy of selling my home, living in a parsonage, and investing my equity in low-cost index funds would generate a similar sort of pull on my heart? Yes. But now, I’m seriously considering parsonage living.