You hear a lot about debt, personal and national, but not a lot about plans to address it. Here’s the big picture(s).

Yes, we Americans are obsessed with data analytics. But maybe we missed something, because despite the dramatic stats about debt in America, not much seems to change. Common Good editors compiled data that show the big picture, and writer Ashley Abramson interviewed three experts about their analysis of the picture.

Personal debt.

Ben Wacek, founder of Guide Financial Planning

How pervasive is the personal debt problem, really?

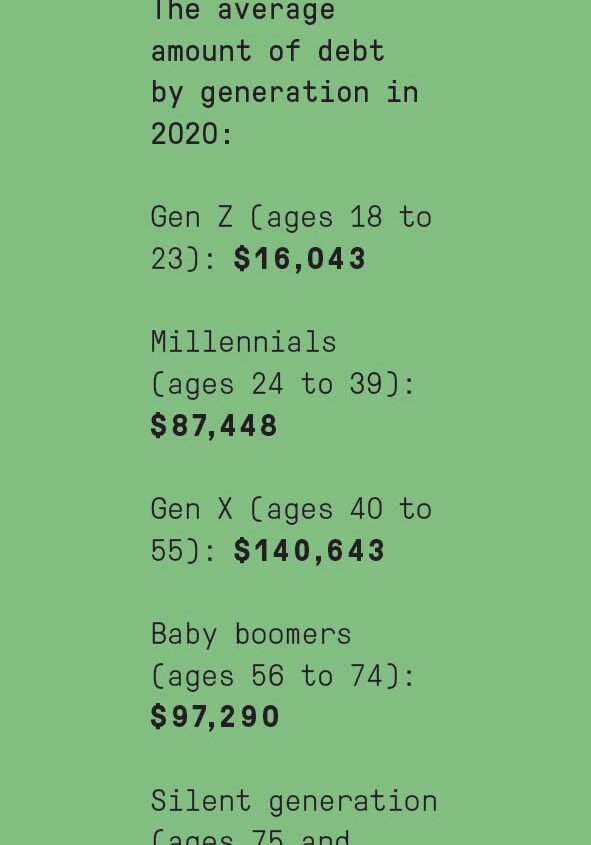

Americans have more than $14 trillion in consumer debt, which breaks down to about $92,000 in average debt per adult. That’s a huge amount, but some people have zero debt, and some people have significantly more. The majority is mortgages, student loans, and auto loans. But many have credit-card debt, too. Debt has really become normalized in our society — many people don’t think twice about putting something on their credit card or financing a Peloton.

Part of the personal debt problem is that prices have raised more quickly than people are earning. There are also systemic factors. Personal finance isn’t taught in schools, for example. So if you haven’t had the privilege to be raised in a family that handles money well, it will be harder for you to forge your own path. No matter the factors, it usually boils down to budgeting. People generally aren’t aware of how much money is going in and coming out.

How “bad” is debt? You hear about good debts and bad debts.

I don’t like to use the terms “good debt” and “bad debt.” There’s a spectrum where there’s bad debt and worse debt, and on the other end, you have full ownership of something.

The worst debt is credit-card debt, because it has the highest interest rate, and it’s often used to purchase goods that lose value. There are exceptions, like medical situations, but often people use credit cards when they just want the money to do something. Where debt may make more sense is buying a house or taking out a student loan because those things have more value.

Rather than just debt or no debt, I’d encourage people to think about the purpose of the debt and the interest rates. If you get behind on credit-card debt, it can get really hard to catch up. You may only be making interest payments, making it more difficult to build an emergency fund that should serve as a buffer between you and debt.

Are the “never debt” advisors realistic, given the pervasiveness of the personal debt?

There would be a benefit to changing our collective mindset around debt, and I agree that we should be using less debt overall. But very few people could buy a home or go to college without taking on debt.

Owning a home is a forced way of saving for many, because you have to pay your house payment every month, and hopefully your house appreciates in value over time. It’s a way of wealth building. But there are caveats. For example, people should think twice about buying more house than they need or taking out a loan with a high interest rate.

And while going to college is a way of investing in your future, it’s important to ask yourself questions when you take on debt. Are there less expensive ways you could get an education? Is the job you can get with this degree realistically setting you up to pay off this debt?

Is there a middle-ground strategy between having $100k in student-loan debt and not going to college until you’re 40?

Weigh your desires against your goals. Some people really value the traditional college experience. But if your goal is just getting a degree, there are some more cost-effective options.

Scholarships are also a significant way to cut costs: I tell students to think of applying for scholarships as a full-time job. I also encourage people to look at all the college options. Often people just pick a name they recognize, instead of looking at the true price tag and, just as importantly, researching financial aid each school offers.

What’s your go-to approach for mitigating debt while also maintaining a life and paying your bills?

It’s not the most fun answer, but so much of it is understanding and tracking your cash flow. If you can understand what’s going in and what’s going out every month, you won’t spend more than you make. And the only way to get out of debt is to spend less than what you make to the point you can make debt payments and pay your bills. There’s no magic way out of it.

I encourage people to look at the bigger picture and understand what they hope to accomplish. When you have goals ahead, like you want to pay off a debt within a certain time period, you have a bigger “yes.” That can motivate you to resist going out to eat or booking a vacation you can’t pay for. Smaller decisions get put into perspective when you have a higher goal.

How can people with debt also achieve their financial goals, like saving, if they don’t make enough money for both?

The most important thing to focus on is paying off higher-interest debt like credit cards. While you’re paying that down, save as much as you can, even if it’s a small amount.

There’s a balance, and people should think creatively to maximize savings where they can. If your employer matches your retirement plan, then contribute what you can to maximize that investment. If you’re building an emergency fund, start small by changing your habits. Pursuing more income is another option to make sure you can pay off debt and save.

The most important thing is to not put off saving just because you feel overwhelmed or behind. That mindset can keep people from trying, which really sets them back. Save $20 a month instead of buying coffee. It’s not a lot, but it grows over time.

Regional debt.

Walter Melnik a professor at Marquette University in Milwaukee

What are we talking about when we talk about state debt?

State debt is money borrowed to fund capital expenditures in a state or municipality, usually related to infrastructure — for example, building roads or highways. There are a few ways states borrow money. There’s something termed “shadow debt,” where states borrow from state employee pensions. If a state needs slack in its budget without raising revenue relative to its expenses, then it might choose not to fully fund pension obligations.

States and local governments can also sell bonds to the general public to fund expenditures. The interest on municipal bonds is deductible from federal income tax, which appeals to people in higher tax brackets.

How does a state’s debt correlate with its ability to function well?

Typically, a state borrows to invest in capital, which can benefit its growth and revenue over time. Often, states borrow up front and then earn more revenue in the future if their tax bases grow or they earn revenue from the asset — for example, a toll road or university. That’s a prudent way of borrowing.

If a state consistently underfunds its pension liabilities, that could result in reduced ability to spend in the future. This can become problematic. It’s hard for people to leave the U.S. as a whole, but it’s relatively easy for people and businesses to leave states when the tax rate increases too much. Then, the tax burden falls on people who are less mobile — less wealthy — and can’t leave the state as easily.

This could be concerning from an economic perspective. For example, a state could borrow to invest in capital that would attract businesses. If when it’s repaying the debt, the business leaves because of higher taxes, that could lower the state’s revenue.

How “bad” is state debt?

More debt is generally a drawback, but it can vary from state to state. Illinois has a severe problem with underfunding its pension obligations, which is a “bad” debt because it’s not earning money on an asset. But even though Texas has high debt from borrowing to fund infrastructure, it’ll likely make more than it has to repay from tax revenue because so many people are moving there.

How is state debt different or similar than household debt and federal debt?

The federal government can create money to buy back its own debt, which is the primary difference. Most states also have a limitation on the amount of debt they can authorize, and the purpose they can authorize it toward. States generally can’t go against their own constitutions like the federal government can, continuously taking on debt to fund operating expenses or balance the budget.

State debt differs from household debt in a few ways. Many personal assets depreciate over time, but state investments tend to add value and revenue that covers the debt. Another distinction is that state debt is usually paid off over different generations of taxpayers. Usually, when individuals take on debt they earn the benefits from whatever they buy now but also have to repay it in a shorter term. There’s also an intergenerational element; people who benefited from government spending in their lifetime may not want taxes to get higher to fund future projects when they’re older and wealthier.

Since states can’t print currency to manage debt, what are the best ways to resolve it?

Raising taxes and reducing spending are the two primary ways. In some cases, the federal government may intervene to bail a state out. Some states and municipalities play a dangerous game where they know the federal government doesn’t want them to default, so they take on more debt than advisable, without the guarantee of a bailout. If severe fiscal distress occurs, a city might declare bankruptcy, but that’s unlikely at the state level. That’s one reason state constitutions are stricter on how much debt they can accumulate.

National debt.

Antony Davies, associate professor of economics at Duquesne University

We hear a lot about national debt. What is that?

National debt falls into three categories. The first is money the federal government has borrowed from individuals, corporations, foreigners, and the federal reserve. The second is money the government has borrowed from the social security trust fund and government worker pensions. Those two together comprise the $28 trillion we currently have — that’s the official debt. There’s a third piece called unfunded liabilities, which is money the government legally doesn’t owe, but from lenders’ perspectives, it looks exactly like the government owes the money. Unfunded liabilities include future social security, Medicare, and pension benefits that the government has promised.

How is national debt different than or similar to personal debt?

It’s different in one way, and the difference isn’t huge. The government, because it will persist — or we believe it will — indefinitely, can keep on rolling its debt over. It doesn’t need to pay off the debt. It just has to make the minimum monthly payment, which is called servicing the debt. Household debt not only has to be serviced, it also has to be paid down, because at some point, people retire and can’t afford to keep paying on debt.

The good news is the government doesn’t have to pay off the $28 trillion. The bad news is $28 trillion is so large that the annual interest costs more than the entire Department of Defense. As we borrow more and more, the annual interest payments will get greater, and those need to be paid every year.

‘Experts’ seem to take differing and opposite views of the extent to which this is a problem. So, if this is a problem, why or why not?

The debt service is a colossal portion of the national budget; it’s circa $700 billion out of about $4.5 trillion, which is about 15 percent. Economically, 15 percent of the budget isn’t a huge deal. It would be nicer if we weren’t paying it; we could do many other things with that money.

Here’s the problem, and it’s less economic than political. We’ve reached a point politically where voters are comfortable with this high level of debt, which is clear because we just went through a national election. Throughout the primaries and all the way through the debates, neither side talked about it. That tells me the politicians are comfortable that voters will let this slide. If that’s the case, it will just get worse. Politicians will continue to spend and rack up debt. We’ll have a $2 trillion deficit this year.

Reportedly, the U.S. owns a high percentage of its own debt. Does that make it better somehow?

When people say that, they’re referring to the second type of debt: money borrowed from social security and government worker pensions. They believe that money doesn’t count because it’s borrowing from ourselves. The federal government has borrowed money from future retirees who are supposed to receive those payments. If they can’t pay that money back, the people who were supposed to receive that money won’t receive payments. It’s identical to this situation: If you live in a house with a few other people and person A borrows $100 from person B, you could say that’s not a problem because we owe that to ourselves. But it’s not ourselves. Person A borrowed from B. If you look at a house as a whole, the net debt is zero, but person B cares.

Why not just print more money?

If we started printing more money to service federal debt, the government could legally fulfill its obligations. But everything will be more expensive, and U.S. dollars will buy less than before.

One smart thing politicians could do in the United States is scale down social security so it only applies to the poor. It was instituted as a barebones safety net; now, the middle class relies on it for retirement when they should be relying on 401ks and IRAs. If we scaled down by a factor of 10, that would go a long way to ameliorate the problem.

This sounds dismal. Can anything positive come of the debt crisis?

All that we’ve discussed lives within the realm of finance. It doesn’t live within the realm of what we can call the real economy. By that I mean our currency could collapse tomorrow and we still have all the factories, machines, bridges, labor, intelligence, technology, and power plants. All that remains, which means we’re capable of producing tomorrow what we produced yesterday.

The difference is with a currency crisis, what changes is people’s expectations. But all our productive capacity was the same as it was before. That means there’s a period where everyone will have to adjust their expectations. But once you pass that, you’ll be back to the world as it was.