Humans have always put on shows for one another. That’s part of who we are. In the present day, what once was a part of life has now, it seems, come to subsume all of it. Because pretty much every aspect of our life now demands a highly curated, and in many cases a quite visually curated, account of ourselves. But there is a real hyper-artificiality here: We can end up conflating who we are and who we want to be — or who we want to appear to be.

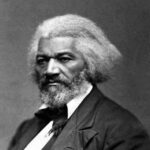

The history of self-creators — or those who have used their creativity to mold not only their art but also themselves, their public persona, their destiny — beginning in the Renaissance and reaching beyond the Kardashians, you could say, to Caroline Calloway and the like, reveals that desire, which is slightly different than our creativity or our reason, could be an engine of humanity.

At some point, we 21st-century humans decided that the most honest thing you can do is try to make yourself the person that you want to be.

The idea that what we want is constitutive of who we are says that our desires themselves are divine. Our self-definition is part of us — but it is not the totality of us.

How do we navigate the best of what creation can do without falling victim to the idea, the trap, that human creativity makes us gods as it were, the idea that our choice and our freedom and our ability to invent are the things that make us human?

The pandemic both supercharged our disembodiment and, perhaps in our loneliness, made us realize that we need something more. Contemporary society is collectively, I believe, hungry for what we might call “the real,” or what is actually true. But it doesn’t actually have a sense of what the real is or where it is rooted. We are collectively searching for something, without a kind of shared reference of what that is. The search isn’t a new one.

The ideal life for the dandy of the 19th century, for example, was life as a work of art — an original thing, something not easily reproduced. There is much to criticize about dandyism, but there is also a valuable form of resistance there that says: My life is not mass produced. My life is something dignified and distinct. The best of the dandies, those who did curate life as a work of art, were working against the backdrop of 19th-century industrialism and the crisis of reproducibility. Everything was being mass produced, and everything was being bought and sold.

If we can say anything universal about the human condition, it is that we are creative, storytelling beings. Our understanding of ourselves comes from shared story and shared language. Whether it’s the sort of material reality of death and decay or the social reality of language, the navigation of all of this is what makes us human. At the same time, the impossibility of coming to firm conclusions of our reality makes us human.

Yet one element of the human condition has in some ways become understood as the primary element of our humanity: our creative freedom or our ability to choose our own path on an individual rather than a social level. We all have to self-create now. For better and for worse, it reflects how we think about ourselves in the world, and how we think about our relationships with one another.

This interest in what humans can conceive of, and whether our dignity lies in that conceptual power, is reaching a kind of weird crescendo in the internet.

What fascinates me about the internet is it’s another reality we have managed to create where what we want is reflected to us. Our desires govern it. We can be connected with people who think like us, who have certain ideological priors that we might also have. Consequently, when we come up against neighbors, friends, family, or people who don’t share all our affinities, we may lack the cultural norms and incentives to make those relationships work. You know, why go to your local bar, coffee shop, or third place and chat with people with whom you might disagree? One of the most important truths of the gospel is that God became a man. This world, with our embodied selves, is sanctified by the fact that our God was in it, not above it, not next to it, but fully in it, that he touched and tasted and walked and was among us. That means there is something holy to the embodied immediacy of this world that is not in the world we have in our heads, not of our imaginations or our fantasies. The gospel invites us to see the world as sanctified, as created, and as in Genesis, good.

In this way, I see a Christian conception of the world as a valuable corrective to the commodification of our bodies or our personalities, wherein we see ourselves as created by God and as images of God. That theological truth challenges us to avoid a certain kind of internet narcissism that gives up our physical, material, and social realities in favor of something that happens only in our own minds or in the collective mind hive of the internet.

As told to Sarah Haywood. This interview has been edited for clarity and style.

Who Are the Self-Makers?

A tiny timeline.

Self-makers? Burton says in her new book, Self-Made: Creating Our Identities from da Vinci to the Kardashians, they’re the “people whose personal creative qualities seemed to give them license to mold not just the art (or poetry or philosophy) they produced but also their public personality and, through it, their destiny.”

The history of self-making? That’s the “account of how we began to think of ourselves as divine beings in an increasingly disenchanted world and about the consequences.” Here are a few key makers.

*The above from Burton’s Self-Made