In England and Scotland, hundreds of congregations have partnered with local police departments in innovative public safety initiatives — with impressive results. A smaller number of churches in the U.S. have embraced this sort of mission, but for those who have, efforts are paying off. The violent crime rate is down and trust between cops and community residents — even in this era of high-visibility police shootings — is improving.

In the Chichester District in England (population 113,000), 10 congregations in the City Angels Partnership with the Sussex County Police provide volunteers who patrol the city’s main pub corridors on weekend nights. Congregational leaders from Revelation Family Church helped pioneer the effort in 2011.

A van of volunteers with water bottles, coffee, and snacks head out before 10 p.m. on Friday and Saturday nights. Some team members stay with the van to provide refreshments and pray for the evenings’ interactions. Others offer conversation, coffee, or help securing a taxicab to those evicted from pubs. This helps keep revelers from becoming victims of alcohol poisoning or of a crime. Police say programs like City Angels decrease the number of calls to which officers must respond so they can focus on more serious situations.

In its first full year (2012), the Chichester District Neighborhood Policing Team reported the Angels contributed to a reduction in violent crime on the weekends. A 2015 study by the Cinnamon Network found it had contributed to reductions in violent crimes (67 percent on Friday nights and 50 percent on Saturday nights) and in injuries resulting from violent crimes. Alcohol-related admissions at the local hospital also lessened 61 percent when Angels were on the streets.

On This Side of the Pond

Partnerships between churches and police are far less common in the United States, but some promising examples exist on both coasts.

Norfolk, Virginia’s Clergy Patrol is a hands-on initiative that launched in 2016, where pastors accompany on-duty officers on weekend nights. Norfolk Police Chief Larry Boone, who is black, says he believed a closer relationship with pastors could help build trust in his community, particularly in black neighborhoods.

Antipas Harris of the Norfolk Urban Renewal Center agrees: “I think the demeanor changes when they realize a pastor is there,” he said during a 2018 interview.

On the scene, Harris said, pastors have the “opportunity to be nonthreatening, mediating community agents between the community and the police.” They can translate for police “the lingo and the subculture in the inner city they may not quite understand because they came from a different context.” Similarly, pastors who are present can “help citizens understand the intent of the police.”

Today, leaders from 17 congregations are involved. And police chaplain Leroy Briggs says that within a year of the program he began to notice a better attitude toward officers.

Harris believes involvement with Clergy Patrol has increased pastors’ influence on the police department. “When you’re on the street you have firsthand observation,” Harris said, “… so the policy development in the boardroom has been heavily informed by experience on the street.”

Higher Trust, Lower Crime

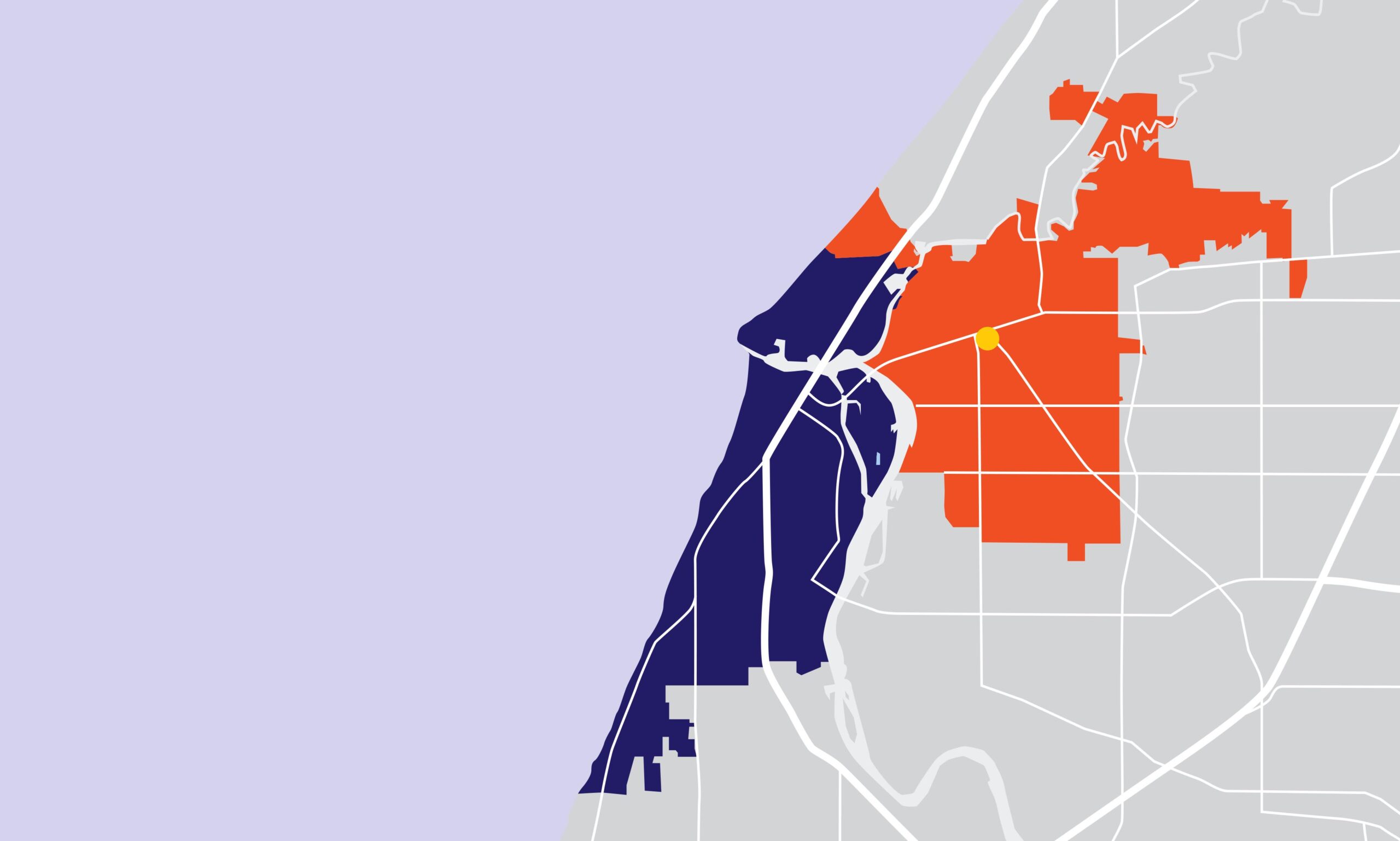

In Stockton, California, congregational leaders and a reform-minded police chief have crafted a trust-building initiative that has garnered national attention. Victory in Praise, a roughly 550-member congregation on Stockton’s east side, has played a key role.

The church houses a faith-based community organizing organization called Faith in the Valley (FITV). Victory’s social justice minister, Toni McNeil, is a full-time organizer with FITV. She has been co-facilitating workshops since 2017 with senior police officers that gather officers, congregants, and community members for dialogues. The organization now includes 120 congregations throughout California’s central valley.

Police Chief Eric Jones has invested enormous personal energy in the work the past several years.

“More than ever, I see trust in police connected to reducing violent crime,” Jones told a journalist in April 2019. He reported that in 2018, homicide rates and nonfatal shootings in Stockton were down. “We’re solving more cases,” Jones said. “Our homicide clearance rate went from around 40 percent in 2017 to 66 percent last year. And when trust goes up it’s safer for the officers going into neighborhoods.”

Improving trust has required courage and persistent work. Jones launched a “listening tour” in 2015, focusing on smaller meetings in homes, churches, and community centers. He wanted to try a different way to listen, especially in the neighborhoods where violence and mistrust ran highest. He began by reaching out to pastors and community leaders.

He conducted about 30 listening sessions, and today he and fellow officers engage in them about once a week. Jones’ willingness to speak honestly about past abuses by police has helped improve community trust. In an address in 2016 to an African-American congregation, Jones acknowledged how cops had enforced slave codes and facilitated lynchings. In a 2017 op-ed in the Stockton Record, he admitted that “former zero-tolerance blanket enforcement efforts in minority communities … created a feeling of police being an occupying force.”

Meanwhile, the workshops McNeil helps lead put cops and community members together as fellow learners in the classroom, with “aha” moments for both.

“We’ve heard the same things over and again,” McNeil said. “‘We want [cops] to be held accountable.’ But without trust, it’s hard to define accountability. Faith in the Valley created shared spaces for accountability through transparent conversations … which was made possible by the culture shift led by Jones.”