Six months and forever ago, you might think the 2020 summer Olympics would provide a kind of balm for the rising global tensions surrounding the assassination of Qassem Suleimani. And maybe the games could be a dose of national unity before a gladiatorial presidential election. But now, we don’t have to tell you, all three of those events seem cluttered out of the national consciousness. We’re in the middle of a pandemic, an outbreak of a novel coronavirus. In the United States, almost 3 million people caught the virus, tens of thousands of people died, and an evacuated economy dropped 50 million jobs in a two-month period. So far.

The coronavirus, and the COVID-19 disease it causes, spawned a health crisis, an economic crisis, and for millions around the world, a spiritual crisis. We can’t figure it all out, we know. But we can help figure out how to figure this out. We invited leaders from around the faith and work movement to join Common Good’s Tom Nelson and Matt Rusten for a round table discussion about the church’s response to the financial crisis of the generation and the future of work when millions are now unemployed, underemployed, or losing their own businesses.

Tom Nelson: The faith and work movement has a long history. But before COVID-19, in most of my context, the movement was primarily focused on work as it relates to individual fulfillment and accomplishment. It was primarily an individualist pursuit to find meaning, using Frankl terms. But after COVID-19, what’s happened is we have been forced to move beyond that individualistic paradigm to a collective one. I think it’s an opportunity for the faith and work movements to press more deeply into the collective aspects of our work. I don’t think that’s just in over-resourced or privileged areas, it’s deeply tied to all of us. I think the faith and work movement, even by its name, was about faith and work, and on the edge were other issues. But I really do believe now we have the “FWE” movement — that faith, work, and economics need to be seen together.

Chris Brooks: Tom is one hundred percent right. I’ve felt this tension between the philosophical aspects of the FWE movement and the practitioners, those with boots on the ground. I would say academicians probably carry more of the weight of the movement in many ways. With COVID-19, we’ve been reminded of the practitioners’ importance, of their value, and how important it is for us to celebrate those who are living this out.

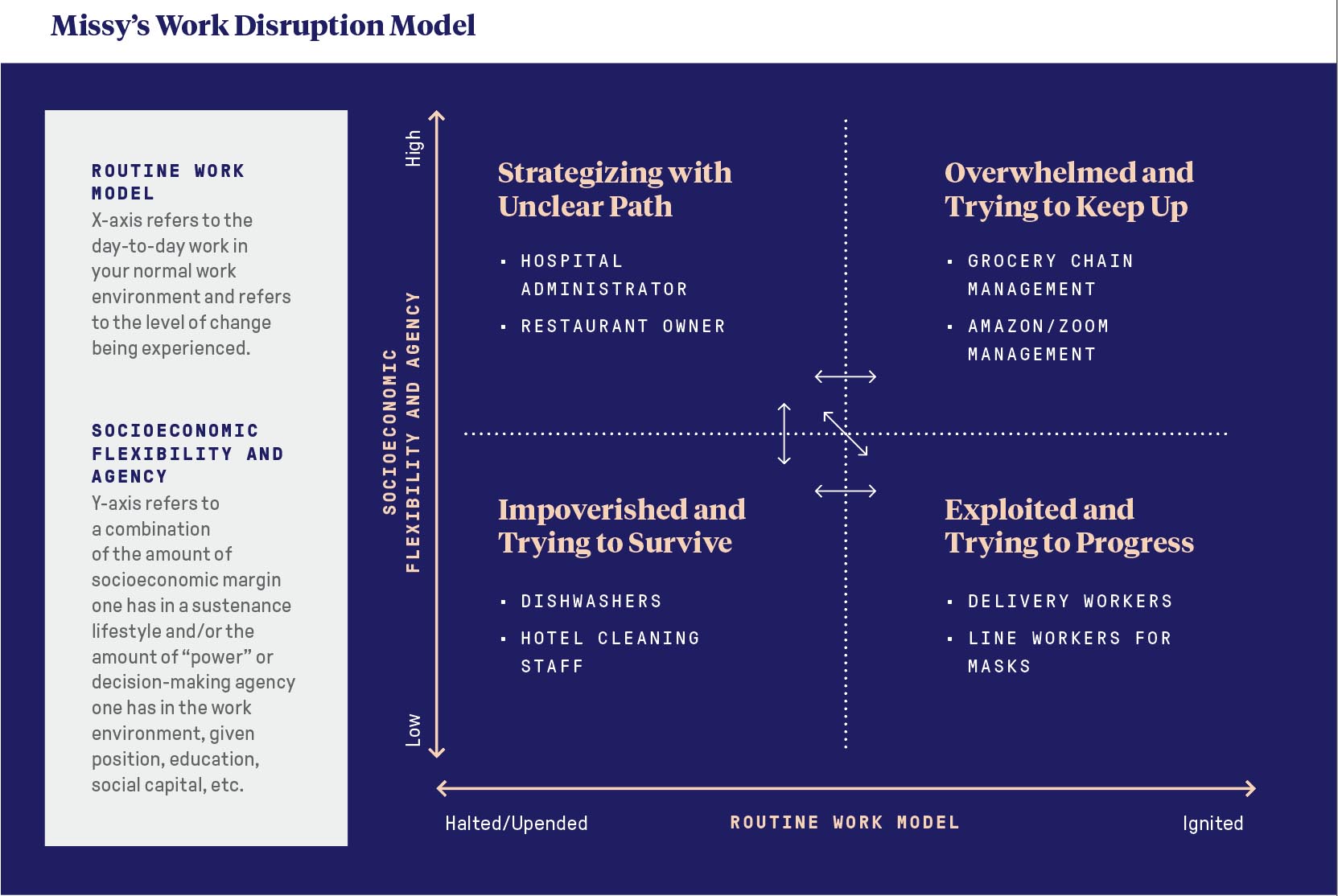

Missy Wallace: Someone recently asked me to speak on a podcast about faith and work as it applies to the disruption in the workplace from COVID-19. Well, how does the church meet work disruption needs when all the needs are different? My sister is a frontline ICU nurse in a COVID-19 unit and has been overwhelmed. I have one friend who has been completely laid off while another is strategizing about lost income and new homeschooling routines.

In trying to figure out patterns of pain points across the many types of work disruption, we developed a tool to help think about the different needs and pain points — and therefore how the gospel intersects them. The model is two-by-two. If you think about a coordinate graph the x-axis refers to the amount of change in one’s day-to-day routine work model before COVID-19. The y-axis refers to a combination of the amount of socioeconomic margin one has for his or her sustenance lifestyle and the amount of power or decision-making agency one has in the work environment, given their position, their education, and their social capital.

So when you start to plot work disruption along these axes, you can start to think about how needs might need to be met differently. What are the spiritual needs? What are the physical needs? What are the temptations, and what is the particular hope of the gospel?

Nelson: I think John M. Perkins has given us the best framework for that answer even before COVID-19. He said, “People need two things to flourish: They need Jesus and a job.” When we’re going to face incredible unemployment levels and work participation levels, that is a compelling mandate to the church, and that framework is probably more compelling emerging out of COVID-19 than it has been since the Great Depression.

Philip Lorish: In the spirit of faithful pushback, while I’m certainly aligned with the spirit of the Perkins idea, I don’t know that everybody needs a job, and I don’t know that, if they need Jesus and a job, that those two are equal in measure. In fact, I think the reality of where we are now means churches should be thinking about what they offer congregants regardless of their employment status. We are clearly at the beginning of a massive unemployment crisis, and if we say that everyone needs a job as a sort of requirement for discipleship, then we’re going to have a lot of people who struggle to know what it means to follow Jesus in a world where work is intermittent, has been taken from them, or is a lot less fulfilling than it was three or four months ago. So, I think the real challenge for the faith and work movement, and churches that are aligned with it, is to address both the very real needs that Missy’s framework puts forward and address the real crisis of meaning coming for a lot of folks who find themselves either unemployed or scared they will be soon.

Wallace: You know, in the North American context, Christianity has become very consumeristic at times. Christianity can be wrongly seen as a self help religion — a kind of model that says, “We’re quite OK by ourselves, but we need you to help us be more moral, raise better children, and comfort us when things are not going our way. Now is an incredible opportunity to showcase reliance on Jesus amidst hardship and to promote that testimony of the fullness of the gospel in all of life. There are people who have been on the margins for a while who probably can teach a lot of people what reliance on God, instead of self-reliance, looks like. God has always been our full provider but it sure is easy to think it is us at times. He has always been there, but we haven’t seen it due to our comforts.

Brooks: I’m so grateful you brought that up, Missy. Because after 20 years doing ministry in an urban context, we do see an interesting dynamic. It’s like when I complain to my homeschooling friends about what it’s like to have to educate my kids at home now: They laugh and say, “Welcome to normal.” And what COVID-19 has done for those who have high socioeconomic mobility and agency is give them a taste of the experiences many live with on a day-to-day basis in urban and rural areas, where poverty is more significant and unemployment is a daily reality. On an institutional level, we need to think about advocacy and activism. There are a lot of edicts coming down through executive order. There are a ton of laws that are happening right now, and the things that are happening in light of a pandemic aren’t being thought through in terms of long-term impact. The church has to be that voice, that buffer that speaks to power and authority on behalf of the people to say, “Wait a minute, what will be the long-term impact of these decisions on the people?”

Matt Rusten: When it comes to churches, I hope in the next 12, 18, 24, or 36 months we can stress the idea of economic opportunity and of framing generosity in terms of gleaning. In the Old Testament, we see a large portion of the community was destitute and had no prospects for getting a “job.” They were called the widow and they were called the foreigner and they were called the orphan. What is so interesting is within that framework, God says to his people, “Be generous and leave some of the work that you could do and give it to someone else for their livelihood.” What would happen if, in every church, it became normal that part of everyone’s generosity budget was money set aside to pay people for some of the work that is left undone — mowing the lawn or cleaning the house and doing any number of side jobs — so that anyone in the community could know that if they’re having a really hard time finding work, having trouble making ends meet, they could always pick up an extra seven hours of work a week to get $480 a month to put food on the table? What if that kind of movement — to frame generosity as generous hiring as much as just generous giving — spread from the institution of the church to the people of the church to members of the community? The church would be providing a “gleaning safety net,” which might be one part of the overall solution.

Jeff Haanen: I think that’s really wise. In an individualistic culture, we are under so many illusions that we can do this on our own, and this crisis is really pushing against that in many different ways. I’m doing this small generosity project about people sharing their stimulus checks right now and it’s been interesting. The impact of it hasn’t been necessarily economic in nature, it’s been people getting to know each other and their neighbors and caring for one another. The real impact of generosity is that you start to see people and they see you. And it’s a giving and receiving that all good relationships are built on. That relational aspect, starting in our hearts and moving out, is really important. Then as we move out and into our daily work, I actually am really concerned about the questions of power. Chris, to your point, there’s so much being told to us about what we have to do right now. It’s constant. This is something that working class Americans have seen for a long time, and they’ve said, “I’ve lost more and more power.”

Fifty or 60 years ago, the church, particularly the Catholic Church, got behind labor unions and was advocating for workers across industries. The faith and work movement has more recently been more white collar and more about influencing culture. But what would it look like for those who do have more agency to leverage that on behalf of those who don’t? I think that is really important because I think, as we move forward, there’s going to be a lot of frustration and people thinking, “I didn’t choose for any of this to happen. Now I lost my job. Maybe I’m even feeling more exposed to contagion.”

Brooks: Jeff brings up so many great points. There are questions that are going to arise and emerge from this season. We have more questions than we do answers right now. It’s been interesting to see new heroes emerge. Who would’ve thought a year ago that we’d be celebrating grocery store clerks? Two years ago, you mentioned grocery store clerks or minimum-wage employees, and you’re thinking about Bernie Sanders and that whole movement. The fight for 15. But in this moment, we’re seeing how deeply dependent our economy is on low wage earners and employees. That helps surface some questions: Have we framed the faith and work conversation the correct way? The church is going to have to learn how to live between the extremes of hyper-libertarianism and hyper-liberalism. It seems like we run to those extremes and dehumanize people when it comes to these discussions.

Wallace: If we think about people who have socioeconomic margin and a great deal of work, there is always the temptation to exploit the workers with less margin or decision-making agency. So in the COVID-19 times, those who are even busier and more overwhelmed and/or more stressed about upending the business model and the profits have a great temptation to further exploit those running the engines of the work who have less agency — whether it’s the nurses or the line shift workers or the grocery store clerks. And at the same time, the people “without” have a great temptation to hold a lot of cynicism and a lot of “us-versus-them” as they process righteous anger. As you think about the model and the quadrants, the gifts and temptations flow through all the quadrants, with the people with agency needing to share the most while also expecting and looking to learn from the other quadrants.

Nelson: I love the conversation around generosity. I want to highlight the generosity that flows out of not only compassion but capacity. When we have this massive disruption in a global economy, we also have an issue of capacity. As a virtuous actor in an economic ecosystem that’s global, how does the church nourish entrepreneurship? How does it nourish — and, Phillip, I’d love to hear more of your thoughts on that — risk-taking not only by gleaning but by supporting new enterprises and building new capacity?

Lorish: Yeah, I think it is. But, again, the most significant part of this moment is that a bunch of people who had stability of some form are now getting a note effectively saying, “Congratulations, you’re an entrepreneur.” I totally agree that that’s psychologically jarring. And while there may be people who are up for that and have somehow uncovered their inner entrepreneurs, what most people expect out of work is stability, predictability, and permanence. For those folks, the “Congratulations, you’re an entrepreneur” line is not well received. And truthfully, the more I work with entrepreneurs, the more I realize how rare the best ones are and how much precarity is built into the whole enterprise. Entrepreneurship is incredibly hard; doing it with virtue, rather than just trying to win, is doubly hard.

Nelson: Can we not stoke a more entrepreneurial spirit within the contours of how people are designed?

Lorish: I think we definitely can. But the best entrepreneurs we work with are ruthlessly aware of their own capacities and limitations. However they market their goods and services, they actually don’t have grandiose visions or believe their own hype. Self-knowledge is the key; and the best can say to themselves, “OK, this is what I can do well, this is what I know I can’t, and here’s a reasonable path to bring whatever I can create to a market of people interested in these goods or services.”

Brooks: We’d be remiss if we didn’t mention the church has to remember that she herself is an employer as well. So what does it look like to care well for the staff that we have, for those that we employ. Even if we have to reduce staff, how do we care well in seasons where we have to lay people off — because that’s a real opportunity for us to model for the other employers in our congregations or in our communities what’s going to be distinctive about the way that we operate as employers.But it’s hard to have this conversation about what the church should be without talking about the church as expositor. We primarily have the responsibility of being expositors of the text; we have to be proclaimers of the gospel. I think part of what this moment will reveal is how culturally conditioned our preaching and discipleship has been. Even when we state things like, “We have to trust the Lord to provide” or “Jesus will take care of us,” there are a lot of cultural assumptions built into that — assumptions that many who have lived in poverty have interpreted differently. These statements — “Jesus will take care of you” and “Jesus will provide” — do not mean that the current status of your life will maintain at the level it is. That doesn’t mean you won’t lose your home, doesn’t mean that you may not have to file bankruptcy on your company. “Jesus will provide for you” has eternal meaning. It definitely has meaning of internal strength, and border, too, but we have to make sure we’re not bringing a middle-class explanation to these circumstances.

Lorish: Another thing being exposed in this moment is how much of our economy is driven by consumption. I’m reminded of the piece in The Atlantic a couple of years ago that reported something like 46 percent of Americans can’t pay a $400 unexpected expense without having to sell something — and, surprisingly, that’s across the income distribution. There’s a general overextension of a large percentage of American families that speaks to the fact that our economy is driven by consumer desire. I would expect that as this new economic reality settles in over the next six, 12, 18 months we are going to see the reemergence of thrift. Lots of us are going to reconsider how we’ve been duped into buying a whole lot of what U2 calls “polyester white trash made in nowhere.”

Nelson: I like that, it is an opportunity for thoughtful followers of Jesus to not only affirm good physical fitness — we certainly talk about that — but financial fitness. I’m just thinking, as you talk, about what it means to be financially fit within the context of economic life, and much of that lack of fitness is indulgence and consumption rather than saving and generosity.