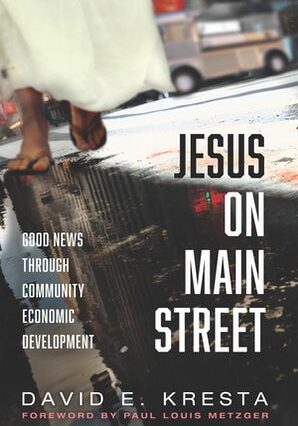

In his new book, Jesus on Main Street: Good News through Community Economic Development, Dave E. Kresta offers in a single volume a robust overview of how church congregations can be involved in 10 community economic development strategies. Kresta’s writing is approachable, and the book contains both practical wisdom and ready-to-use tools. For congregational leaders who desire to see their churches engage more effectively and intelligently in the fight against poverty, Jesus on Main Street is a must-have.

The book was released in July from Cascade Books.

Too many congregational leaders fail to see that churches are economic actors and that engaging in economic development is part and parcel of fulfilling the Great Commandment. My friend Tom Nelson, a pastor and the president of Made to Flourish (which publishes Common Good), relates that the most common conversation he has with people inside and outside the church centers around economics. That’s not surprising, since, in one author’s words, we wake up every morning in an economic world. Congregations do not need to make community economic development their primary focus. Congregations do need to love their neighbors well, and that means caring about — and practically investing in — economic flourishing for all.

Jesus on Main Street may feel intimidating to some readers because of its comprehensiveness. Kresta, who teaches at Portland State University and is a fellow at Duke Divinity School’s Ormond Center, discusses many strategies of what’s called community economic development, or CED, some of which are not particularly practical for many congregations. But consider this a reference book, a field guide of sorts, that lays out all the various approaches to CED — from the simplest to the most complex — and begins to explain them and how they fit together. The goal when reading a reference book is not to understand it all or implement it all. Rather, the goal is to get a good introduction to a field of practice and, with that big picture in mind, become better prepared to find one’s niche within it.

Doable Strategies

Readers can focus their attention on the 101- and 201-level strategies that best fit their community and leave the more complicated ones for future consideration. Below are some of the most doable strategies discussed in Jesus on Main Street.

Supporting microbusiness. Kresta suggests church leaders or volunteers get to know small business owners in a distressed neighborhood and offer them support — by sharing office space, linking owners with skilled congregants able to assist them in growing their businesses, and encouraging parishioners to patronize these small businesses. Another way to provide support is to launch a microloan program offering no- or low-interest loans to existing or aspiring entrepreneurs. Although not discussed in Jesus on Main Street, the 1K Churches initiative is one that offers helpful implementation resources, guidance, and inspirational stories of churches that have multiplied their economic impact through smart microfinance.

Implementing a jobs program. Some low-income adults need help preparing for, obtaining, and retaining employment. Congregations have people who (a) know what soft skills employers are looking for; (b) can coach people in interviewing and job searching; (c) can serve as cheerleaders who provide encouragement, moral support, and transportation and childcare assistance for job-seekers; and (d) have knowledge of job openings. Good, biblically based job training curriculum is already available (e.g., The Chalmers Center’s Work Life program). Additionally, as Kresta notes, the church can partner with others in the community to make a jobs initiative more effective by gearing the program towards employment opportunities in the trades or inside “anchor institutions,” like local hospitals or universities. Both these tracks offer possibilities for landing “good jobs” (i.e., jobs paying a living wage and/or offering stable, predictable work schedules).

Repurposing space. Too many church buildings are underutilized throughout the average week. In the face of persistent poverty in our communities, this latent asset needs to be activated. Kresta gives examples of churches sharing kitchen space with local food entrepreneurs and turning rooms into maker spaces where artisans can learn new skills or use specialized equipment to make products for sale. White Rock United Methodist Church in East Dallas, for example, repurposed its large basement to create The Mix. It is a co-working space that offers not only Wi-Fi, desk space, and meeting rooms but also an artist studio with a double sink, a textiles workroom, and a commercial kitchen.

Intentionally purchasing. Kresta emphasizes the importance of recycling dollars within a neighborhood. Churches can contribute to this through intentionally patronizing local vendors and locally owned stores. He also discusses purchasing cooperatives. The Community Purchasing Alliance, composed of several Washington, D.C.-area churches and nonprofits, is a textbook example. It is creating more affordable access to services such as HVAC, landscaping, electricity and natural gas utilities, and trash hauling. Members of the co-op are saving money on these expenses while simultaneously supporting local entrepreneurs. Fifty-eight percent of the contracts the Alliance awarded in 2019 were with local small businesses.

Advocacy and organizing. This can take a variety of expressions: mobilizing congregants in support of a private or public investment that offers promise for improving economic opportunities in a vulnerable neighborhood; joining in revitalization efforts around a community’s main business corridor by sponsoring cleanups or helping to implement streetscaping projects; or working with neighborhood organizations to produce a “community benefit agreement” (CBA) when a traditional economic development initiative is being proposed (e.g., a new sports stadium, a major housing development, a corporation wanting to build a new factory). A CBA is typically based on community organizing that gathers local residents together to hear their concerns and ideas about the proposed development. The CBA articulates measures these residents want to see private and public developers include in the planning, so that the benefits of the initiative reach them. For example, a CBA might ask that a certain percentage of the housing built be affordable, or that developers use community training centers as “first sources” for hiring workers, or that they prioritize local women- and/or minority-owned firms as suppliers.

Putting Jesus on Main Street to Work

Kresta’s book has two things working against it, but both obstacles can be overcome. The first issue is beyond the author’s control: bad timing. Most pastors will find this book challenging, as it calls congregations to some new and likely unfamiliar things. During the pandemic, that’s probably the last thing overwhelmed and exhausted pastors want to hear. Thankfully, pastor’s aren’t working alone: If you’re clergy, invite a few members of your congregation into a research opportunity. Buy a few copies of the book and give it to three people in the congregation: perhaps a person who sees themself as a “kingdom” businessperson, a lay leader involved with the church’s local missions efforts, and an energetic congregant known for passion around addressing poverty. Ask these three to read it, pray over it, and discuss it together. Ask them to come up with some answers to the question: In light of the strategies and examples given in this book, what could you imagine our church doing to better serve economic needs in our community?

Kresta’s challenge to put these ideas to work is a worthy one, but his argument in Jesus on Main Street brings with it some risk to its own reception. Jesus on Main Street’s framing may be off-putting to some readers. In it, Kresta opposes what he calls “traditional” economic development, or TED. He defines this as “trickle-down” capitalism that might spur economic growth, but is not likely to do so equitably, and he presents CED as the answer. This approach falls short because his critique of TED is short and lacks a strong presentation of evidence to undergird his claims. Personally, I am sympathetic to Kresta’s concerns about who benefits from the wealth creation and job opportunities TED produces. But Kresta’s brief discussion is unlikely to persuade economic conservatives.

Since he admits that “a full critique of the current state of capitalism is well beyond the scope of this book,” he would have been better off to frame CED strategies as practical outworkings of neighborly love rather than as the answer to the evils of TED. If congregations are going to pursue CED in the ways Kresta recommends, then business people in the pews are going to have to play a major role. I don’t mind that Jesus on Main Street might ruffle some of their feathers; to the extent that some have blindly adopted laissez-faire economics, some ruffling is warranted. I just worry the book does too much of it, and too often. How unfortunate if the very readers with the skills and experience to put the book’s strategies into action end up throwing the book down because it strikes them as leaning left economically. I recommend that pastors encourage their business leaders to give the book a chance and emphasize that the strategies discussed are enterprise solutions to poverty. They are practical methods that redemptive-minded business people can put to work towards achieving scripture’s beautiful economic vision, with a focus on opportunity, creativity, work, risk-taking, justice, wealth creation, and restoration.