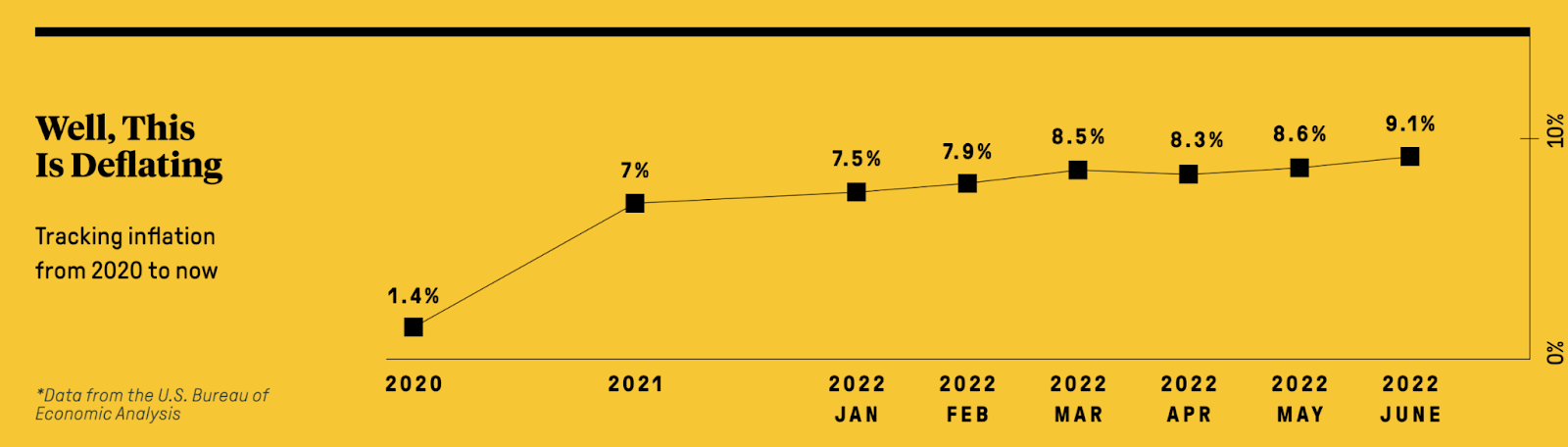

Americans are rightly perplexed about the current state of the American economy. Some are even asking if we are reliving the 1970s. Gasoline prices are more than double what they were this time last year, and inflation is at a 40-year high. The most recent consumer price index (CPI) is 8.6 percent. The Federal Reserve’s target for inflation? Two percent. We have even started hashing the Misery Index, which measures inflation and unemployment rates combined — which hit its peak of 22 percent in 1980 and has now inched back up to 11.5 percent, a significant leap from its five-percent rate in 2015.

All of this is deeply connected to personal well-being, which along with the economy has been in flux. Inflation acts as a tax on our incomes, and the worst part is that it hurts those at the bottom of the income distribution the worst. When you are living paycheck to paycheck, an almost-nine-percent inflation rate might mean that you can’t afford groceries or your day care bill this week. It’s a problem that has spiraled out of control — and we need to get it fixed now.

The economic crisis we experience today is a result of more than just the COVID-19 global pandemic, which created supply chain blockages, manufacturing dilemmas, and a boomerang of gross domestic product (GDP). The lockdowns and shelter-at-home policies in the early days of the pandemic exacerbated a 100-year problem: a growth in the size and the scope of the federal government.

In the year 1900, government spending was 6.9 percent of the GDP. Today, it’s 41 percent. Moreover, federal deficits are expected to increase over the next 10 years. Within a decade, Medicare and Social Security face insolvency. These problems are longstanding and bipartisan, and both the fiscal policy and monetary responses to the pandemic have sent the economy into a tailspin. The consequences of our fiscal policies over the past century are due.

Economists Alex Salter and Peter Boettke, authors of “Money and the Rule of Law” explain our federal deficits: “Starting in 2020, Congress ran huge deficits and the Fed bought up the resulting bonds. More than 50 percent of new government debt ended up on the Fed’s books.”

This element of inflation is on the supply side. The lesson of 20th-century economist Milton Friedman is that money supply must be in accordance with money demand. Excessive money supply through quantitative easing or other means will cause disequilibrium — including inflation.

Salter goes on to warn us that “we still need Milton Friedman,” making the case that technocratic monetary policy fails. Interfering with interest rates, asset prices, and exchange prices all of which are relative prices and convey essential information regarding underlying levels of scarcity, disrupts the process of market correction. We would do better to let the market work and to limit monetary policy to its primary function, which is focusing on keeping money supply in accordance with aggregate demand and limiting monetary policy strictly to that rather than going beyond its mandate and veering into fiscal policy. Yet policymakers and central bankers like discretion over rules, they seek short-run wins dismissing the longer-run consequences.

The pandemic accelerated fiscal spending to the tune of $3.7 trillion spent on COVID-19 relief, while the Federal Reserve pursued a variety of suspicious monetary policies including quantitative easing, which looked like purchasing $3.3 trillion in government debt in just two years. Simultaneously, COVID-19 restrictions, supply chain issues, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and transportation blockages confounded these issues. Thus, the current inflation is caused by both supply and demand shocks.

And now, the Fed is attempting to curb inflation by raising Fed interest rates. The Fed raised its benchmark rate by .75 percentage points in June and made a similar move in July. This was the most aggressive Fed rate hike since 1984.

Will Luther, director of the Sound Money Project at the American Institute for Economic Research, suggests it may be too little too late. In other words, this is a problem that to some extent could have been avoided. Profligate stimulus spending and unorthodox and aggressive policies got us here. Columbia law professor Lev Menand suggests that during the pandemic the Fed was given too much power through the CARES Act, in which Congress authorized it to lend outside of the financial system.

This allows the Fed to become politicized and, as Salter suggests, creates opportunities for the Fed to extend beyond its mandate.

(Data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis)

There are many suggested culprits of our current inflation — from Putin to greed — but the harsh reality is that money supply must be reconciled with money demand.

Economist Pete Earle explains that while the Fed was calling price rises in early 2021 “transitory” it was “tasked to craft monetary policy explicitly supporting social justice, climate change, ESG, and other political goals.” The Fed didn’t stay in its lane. Now we find ourselves in a position requiring painful corrections.

The short-term steps to ease our economic pain include the Fed raising the federal funds target rate to curb growing inflation, which will restrain consumer spending and make purchasing a home more expensive. The longer-term steps must include restraining Fed behavior to its original mandate and leaving fiscal policy to Congress.

Sometimes the answer to what the government needs to do to help in a crisis is that it just needs to get out of the way. In this case, the Fed must take explicit steps to curb inflation, but it also must stop engaging in monetary policy. The Fed cannot pursue easy money forever, and to avoid future episodes of unexpected and persistent inflation — it must be restrained by rules and the rule of law.