It was December 1984. I watched throughout the month as wrapped presents slowly appeared beneath the Christmas tree. One large box had my name on it. I knew what it was — the number one item on my list, the Matchbox Voltron Lion Force set. Five glorious diecast lions in black, green, red, blue, and yellow, that when combined formed the tall, weighty robot Voltron. What I had most hoped for was soon to be mine; and all I had to do was wait.

After waiting (and waiting), Christmas Eve arrived. It took begging, but my two younger brothers and I received permission to open one package each before we went to bed. We went straight for the packages containing our most hoped-for gifts. I waited as my youngest brother opened his selected present. Then I waited some more as my next-to-youngest brother opened the gift of his choice. Both were elated with the toys they anticipated. Then it was my turn. At last, the appearance of the glory of my great gift, Voltron, had arrived.

“Voltron! Voltron! Voltron!” I boasted, as I tore through the paper wrapping to uncover a nondescript brown cardboard box. That was no surprise; putting toys in other boxes was Mom’s way of disguising them. Undeterred, I broke the cellophane tape and opened the box. There it was, in all its tall, weighty, metallic glory — a trash can.

The trash can had a basketball hoop attached to it. So, I spent the evening shooting wadded-up balls of wrapping paper into the trash can, pretending it was awesome. It was not. It was awful. My confidence in this gift proved to be a false hope. I was disappointed and ashamed, but I would not allow my face to show it.

Disappointment and shame are not what I remember most about that fateful Christmas Eve though. I recall a distinct inability to love my brothers. They’d received the gifts they hoped for. I had not. Instead of rejoicing with them, my heart turned inward and bitter. I wanted to pretend my gift was better than theirs. I refused to share in their joy and instead shriveled up in selfishness. The idol of possessions killed my love for my neighbors.

Israel’s hope misplaced

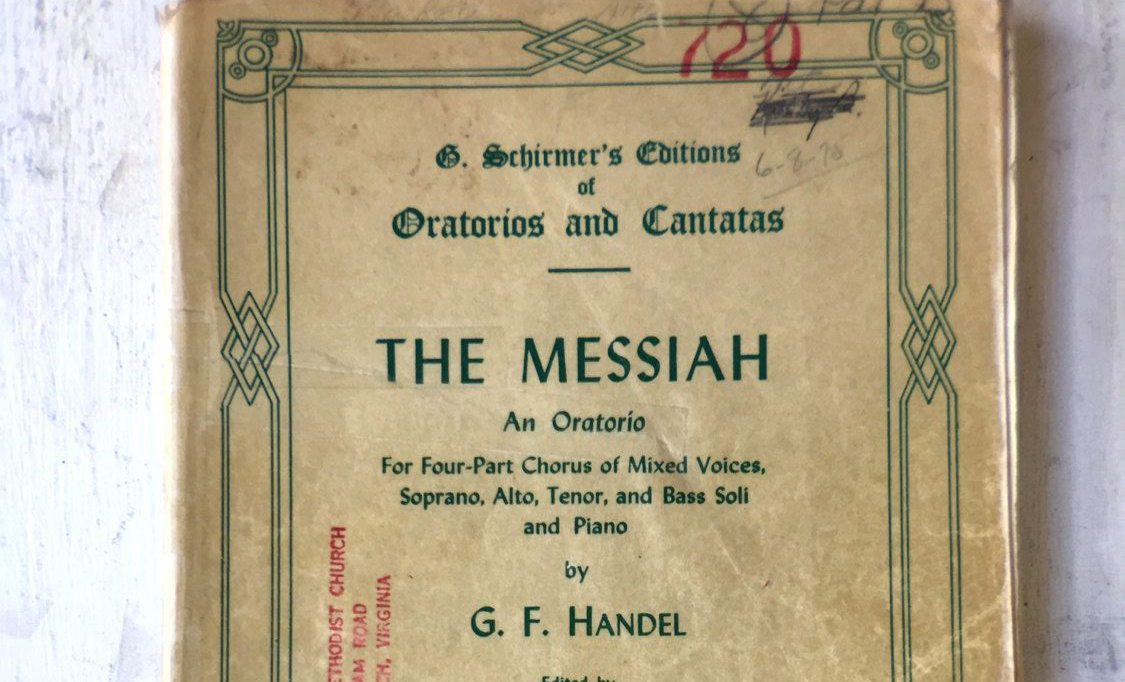

For four weeks, Christians around the world enter a season of expectation, waiting, with anticipation greater than that of my younger self at Christmas 1984, for the birth of Jesus. In Advent, we look to Israel’s hope of a coming Messiah, who would bring to pass all of God’s promises. As Christians, we know that promised servant is Jesus of Nazareth, the crucified, risen, and returning king. Thus, Advent meets us where we are now — a New Covenant people awaiting the return of the Messiah.

The first Sunday of Advent is traditionally associated with hope, particularly the hope presented to Israel through the prophets. Today, the word “hope” is often used for wishful thinking — “I hope the Hawkeyes don’t embarrass the state in a bowl game again.” In Scripture, “hope” is something more substantial. Hope is a confident assurance of what will be in the future; it is the conviction of what has not yet arrived. As Paul writes:

Hope that is seen is not hope, because who hopes for what he sees? Now if we hope for what we do not see, we eagerly wait for it with patience. (Rom 8:24–25).

This kind of “hope” features significantly in Isaiah’s message. Isaiah proclaimed a glorious future in which death would be swallowed up, and the Lord would throw a magnificent party for his people (Isa 25:6–8). Those who “waited for him” — that is, set their hope in him to fulfill his promise of salvation — would rejoice and be glad (Isa 25:9). But Israel proved impatient and unwilling to wait.

The Lord tells Israel, “you have rejected this message and have trusted in oppression and deceit, and have depended on them” (Isa 30:12). Oppression and deceit offer a kind of hope: They promise that if we treat others cruelly and deny them justice, the future we desire will be ours. But the Lord says that what we gain from this “collapse will come in an instant” (Isa 30:14).

Yet instead of hoping in the Lord, Israel would shift its hope to its military might (Isa 31:1). Though this might offer the hope of protection in exchange for a pledge of allegiance, these are only false gospels that ultimately disappoint: “Egyptians are men, not God; their horses are flesh, not spirit. When the Lord raises his hand to strike, the helper will stumble and the one who is helped will fall; both will perish together” (Isa 31:3).

And instead of looking toward the Lord, Israel would be tempted to serve idols, which promised those who worshiped them the future they hoped for. But like every hope outside the Lord, this was a path to collapse: “They will be turned back and utterly ashamed—those who trust in an idol and say to a cast image, ‘You are our gods!'” (Isaiah 42:17).

It is not a matter of whether or not Israel has hope, but whether they have the right hope. Everything Israel was tempted to turn to — injustice, alliances, military strength, idols — promised hope but delivered only disappointment and shame.

Hope in our own season

I never did get that Voltron. I’ve looked for it as an adult, and, to be honest, it looks rather unimpressive. Nearly 40 years of life offer a bit of perspective. And it will be like that when Jesus returns — we’ll look back on everything we wanted in this world and find it unimpressive in the light of his glory. We’ll wonder why we ever valued it so highly. But let’s not wait for his return for this realization. Let’s live by faith—”the reality of what is hoped for, the proof of what is not seen” (Heb 11:1).

Likewise, we look to the story of Israel with perspective. The people of Israel put their hope in comfort and safety. This meant devoting their earthly resources to crafting idols or paying tribute to foreign leaders. Ultimately, it meant practicing deceit and oppression. They did not love their neighbor as themselves. They did not pursue justice, correct the oppressor, defend the rights of the fatherless, or plead the widow’s cause (Isa 1:16-17).

The object of our hope shapes our ability to love.

At Christmas, we celebrate the arrival of the hope promised by the prophets. That hope arrived through the birth of Jesus. All God’s promises find their fulfillment in the Messiah’s life, death, resurrection, ascension, and return: “For every one of God’s promises is ‘Yes’ in him” (2 Cor 1:20). In his life, Jesus lived the righteousness we’ve rebelled against. In his death, our Lord received the punishment for our sins. In his resurrection, Christ demonstrated that sin, death, and the devil have been destroyed. In his return, the Lord will raise us from the dead in a glorious resurrection like his — imperishable and incorruptible.

That is a glorious hope — and it is a transformative hope. Because our hope is not of this world but kept for us in heaven, we do not need to cling to the things of this world. Because our future is guaranteed in Christ, it faces no risk when we are generous and sacrificial in loving others. Consider how Jesus makes this point in Luke 12:31-34:

Don’t be afraid, little flock, because your Father delights to give you the kingdom. Sell your possessions and give to the poor. Make money-bags for yourselves that won’t grow old, an inexhaustible treasure in heaven, where no thief comes near and no moth destroys. For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.

When our hearts are satisfied with all we have in Jesus, our hands stop clutching worldly things, our power and our possessions, in fear and start distributing them in joy.