All eyes are fixed on the bond market. Data for the U.S. 10-year Treasury note says that yield hit five percent this week, for the first time since 2007.

That five percent is extremely important. The rate on the so-called US10Y impacts how much banks charge you for a car loan as well as how much interest the government must pay on its debt, and it’s rising fast. In some ways, the rate affects everything else. Here’s why.

What happened

To understand the mechanics of why that happens, we need to first understand some technical financial modeling.

A critical tool financial professionals use for predicting the future is a discounted cash flow model, or a DCF for short. This one Excel spreadsheet underpins the entire U.S. economy. And I’m being a little hyperbolic in saying that, but not by much. It’s one of the core tools MBA grads learn in business school, and it’s essential to understanding how the Fed’s policies affect your spending decisions.

Imagine you’re the head of a big acquisition: You’re in charge of investing up to $1 billion dollars to buy a company. How much should you spend? Should you use cash, stock, or debt? What is the return you expect, and over what time horizon?

Enter our trusty DCF.

One of the components of a DCF is the weighted average cost of capital, or the WACC. This number helps you estimate how much it will cost to finance this acquisition. The calculation shows the mix of equity (like stock) and debt you could use and how much you’ll pay for each. Working on the model, a financier will tinker with different mixes of each in their capital structure to see what mixture yields the best return.

Stay with me — this is where the US10Y comes into play. That will determine how much equity will cost you. By adjusting what’s called the “risk-free rate,” or the rate of the US10Y, financiers can estimate the cost of equity. It’s called “risk-free” because it’s the rate of return an investor can expect that’s virtually free of risk — this is due to the fact that, in order for this money to not be safe, the federal government would have to default, which has never happened and is very unlikely to happen in the near future.

Banks use the US10Y as a gauge for determining the interest rate on their loans, which is debt to you. In the 10 years before 2020, that rate was around two or 2.5 percent. When the rate jumps from 2.5 percent to five percent, the cost of financing an acquisition with equity goes up, just like it would when you want to finance a car or house, because investors will want a higher return on their money, since they could now easily get a modest return of five percent by just investing in a U.S. Treasury note. This impacts the return you could expect by buying a company.

To recap, you as the investor want a high return for your money if you buy this company. You could get five percent risk-free. Because of that, you’ll want a higher return if you buy a company, which increases the cost of equity for this acquisition. That increases the overall cost of capital, which reduces the “free cash flow” from the acquisition when we project it out for several years and “discount” it back to today’s value, hence the “discounted cash flow” or DCF model.

A few economic terms explained:

US10Y

The 10-year Treasury note is a debt obligation issued by the United States government with a maturity of 10 years upon initial issuance. A 10-year Treasury note pays interest at a fixed rate once every six months and pays the face value to the holder at maturity. The U.S. government partially funds itself by issuing 10-year Treasury notes.

DCF

Discounted cash flow (DCF) refers to a valuation method that estimates the value of an investment using its expected future cash flows.

DCF analysis attempts to determine the value of an investment today, based on projections of how much money that investment will generate in the future.

WACC

Weighted average cost of capital (WACC) represents a firm’s average after-tax cost of capital from all sources, including common stock, preferred stock, bonds, and other forms of debt. WACC is the average rate that a company expects to pay to finance its assets.

WACC is a common way to determine required rate of return (RRR) because it expresses, in a single number, the return that both bondholders and shareholders demand to provide the company with capital. A firm’s WACC is likely to be higher if its stock is relatively volatile or if its debt is seen as risky because investors will require greater returns.

From Investopedia.com.

Let’s look at what this model from the Corporate Finance Institute looks like in two parts so you can see what an investor sees.

In this first image, I’m starting with a WACC calculation, a line of which includes the risk-free rate of 2.5 percent. When I increase it to five percent, the total cost of capital or WACC jumps from 8.33 percent to 10.11 percent.

Now let’s look at the overall DCF model. When I increase the “discount rate” (the WACC) — the total value of the free cash flow projected into the future, discounted to today — here shown on a per-share basis — decreases from $19.83 to $10.51. This means it costs more for me to finance that deal over the next several years. If you were a lead investor, you may think twice before dumping a ton of money into a business with that kind of projection.

It’s this kind of calculation that every business leader and even every consumer is doing when they think about putting their hard-earned dollars into an investment. That includes multi-billion-dollar mergers and acquisitions, car and student loans, mortgages, and even that $10 you want to invest in your Robinhood account. Bankers also use the US10Y rate as a benchmark for the interest rate on their loans, which is why it’s so important for the economy as a whole. The higher the rate on U.S. Treasury bonds, the lower your return on invested capital. Lower returns lead to hesitation. And that’s how the US10Y rate slows down the economy.

Why it matters

This slowdown matters because, as I’ve written before, it takes time to see its effects in the real economy.

In 2005, years before the actual economy became a disaster during the Great Financial Crisis, investor Michael Burry saw what was coming and made initial bets on bad mortgage loans. Those bets were described in the book and film The Big Short.

Burry could tell that if the economy slowed down, those mortgages would turn bad, and the value of big banks’ investments in them would go bad, all based on similar calculations as used in a DCF. Three years later, the economy was in turmoil.

Today, the rate on the US10Y is back to where it was in 2007, just before tremors worked their way through the economy in real ways. And it’s rising quickly, much like it did in the early 1980s when the economy ground to a halt.

This phenomenon is happening at a pivotal moment. Pandemic-era relief programs have ended, student loan payments have resumed, wars have broken out, small business bankruptcies are on the rise (as are labor and supply chain costs), and winter is coming.

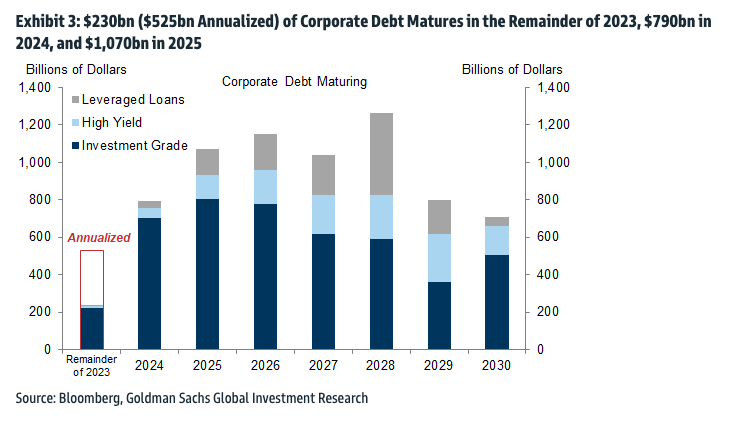

Additionally, what has many investors really worried is that, in the next year and the year after, a “wall of debt” will be maturing. Companies took on lots of debt when the US10Y was around two percent:

And with higher interest rates, that debt will need to be paid back if these companies can’t restructure or refinance it. Even if they do refinance it, the debt will cost even more due to higher rates, which puts pressure on their available money.

The point is that the little numbers you read about in the financial press can have big impacts.

Yet it all comes down to how financial professionals predict the future. As for me and my house, I’m a bit of a bear, so hold this analysis with a grain of salt.

Still, all is not well in the market. May God help our interest rates.