You’re having a heated discussion over a hot-button issue with a friend. At the height of the conversation, you both reach for your phones to prove your point. After scrolling through your Instagram, you find the post you were looking for. You read the post aloud and sit back with a satisfied smile, content you’ve won the day. But the debate isn’t over. Your friend finds a post on their feed that directly contradicts yours, and both appeal to the same information but come to radically different conclusions. You’re both convinced you’re right, and your social-media feeds agree. Neither one of you concedes.

Sound familiar?

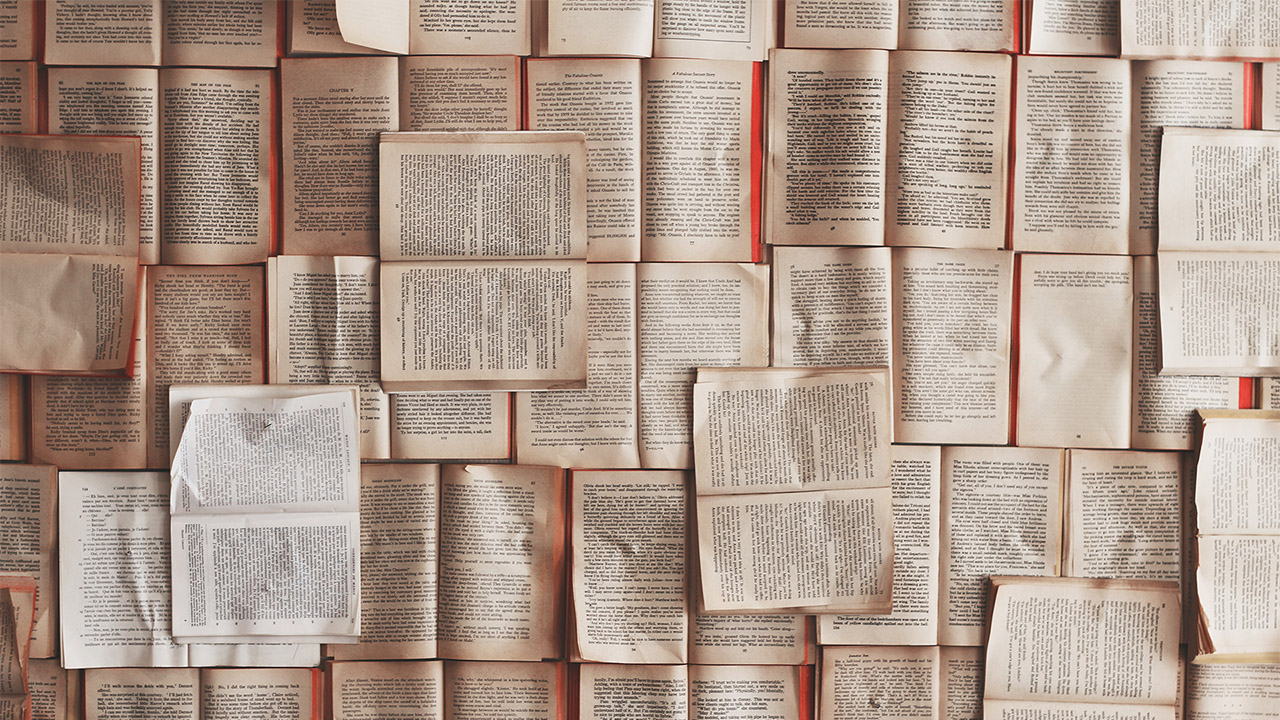

Most of us like to believe that we’re objective, that we can slog through the stories and spins and arrive at the truth, that we’re concerned with the facts and nothing else. While this level of objectivity is admirable, it’s impossible.

All of us suffer from what psychologists call confirmation bias, or “the tendency to process information by looking for, or interpreting, information that is consistent with one’s existing beliefs.” Our brains are overwhelmed with information, and we search for the easiest ways to process data. Naturally we look for the things that align with what we know and believe about the world — and we interpret the data accordingly.

This means that our “objectivity” is, in fact, subjective. We filter the world through a narrow lens called self, leading us to believe that the information we receive aligns with what we know to be true.

This also means that “the raw facts” we consume aren’t raw at all. Like us, writers, historians, and journalists are also prone to bias. They knowingly and unknowingly filter and arrange facts to fit their internal frameworks. Confirmation bias affects both what we consume and how we create. Prone to self-delusion, we easily ignore the voices that challenge us in favor of voices that tell us what we want to hear. While this isn’t a new problem, it’s exacerbated by the internet — and the almighty algorithm.

The Social Dilemma, a documentary film released by Netflix in 2020, explores the inner workings of platforms like Instagram and Facebook. While Facebook denied some of the claims made by the film, the film does accurately portray how the social platform algorithms work. Rodd Lindsay, a former data scientist at Facebook, wrote in a 2021 New York Times op-ed piece that social media platforms have embraced “personalization, spurred by mass collection of user data through web cookies and Big Data Systems, and algorithmic amplification [and] the use of powerful artificial intelligence to select the content shown to users.” He goes on to state that these algorithms, like the ones used to power Facebook, Youtube, and TikTok, “perpetuate biases and affect society in ways that are barely understood by their creators, much less users or regulators.”

In other words, we get what we put in. Our online lives are on an infinite feedback loop, giving us exactly what we want. Test it out for yourself. Look at the suggested content. You’ll rarely find a view that challenges you, and while this might make for trigger-free web surfing, it does little to prepare us for honest discourse, debate, and discussion.

But how do we combat the feedback loop? Prone to our own biases, how can we critically engage with what we read online and dialogue with others, especially when it feels like swimming upstream?

William Blake, the great English poet, adds a bit of urgency to answer that very question. He wrote in “A Memorable Fancy”:

“The man who never alters his opinion is like standing water, and breeds reptiles of the mind.”

A prophetic writer, Blake speaks to the very issues we face today. Here he notes that those caught in the throes of self-deception are those who are unwilling to change their minds. Their inability to be open to new ideas and countering opinions creates aberrations, thoughts that refuse to be challenged by reason. They breed disease in plague-like standing water, denying any fresh source that might shake up their intellectual cesspool.

Blake advocates for intellectual humility, the ability to hold our beliefs with open hands. This doesn’t mean we believe nothing, but rather that we are aware of the limits of our own reason, that total objectivity is beyond us — and that being human, we are prone to misunderstanding, and we get things wrong.

Intellectual humility opens the door for critical engagement, which is the only way to combat the feedback loops (or to clear the intellectual cesspool). To critically engage anything, we must learn to do so with humility, curiosity, and depth. With total objectivity out of the question, critical engagement requires both an honest assessment of biases and an understanding of the context of the information with which we engage.

The good news is it’s not as daunting as it sounds.

Grant R. Osborne, New Testament scholar, advocates for what he calls the hermeneutical spiral — in short, a process by which we can better engage the media we consume. This process begins with the reader’s point of entry (their worldview, presuppositions, cultural norms, etc.). By becoming aware of our biases, beginning with what we know, we acknowledge the preconceived notions that shape how we engage with information. Having done that, the reader can look at the work in question, examining the context in which a particular piece is situated. Who wrote it? For what publication? What is their angle, their politics? These questions help us get beneath the surface and into the substructure that undergirds our consumption.

Let’s walk through Osborne’s spiral, considering the news we consume. First, we assess ourselves before we begin reading, acknowledging the biases that might make us dismiss what we are reading.

Then we assess the source, acknowledging the biases there. When we approach an article, we must not assume the author or the institution’s objectivity. Before we begin reading we must take the time to assess not only what we’re reading but also where it comes from. We need to ask: What does the author believe and does this publisher or organization have a known agenda? On top of that, we must consider the validity of the source: Is it peer reviewed, do they abide by certain ethics and industry standards, and do they have a known track record of credibility?

Only then are we ready to engage the text itself. We must ask if it is well researched, if it is a fair assessment of the author’s opponents, if the author avoids logical fallacies (straw-manning, begging the question, special pleading, or ad hominem attacks). After these careful considerations, we can respond. This is intellectual humility in practice. Once we learn to engage critically in this way, we can begin to read across the aisle, intentionally engaging with views that directly contradict our own.

If we’re honest, we rarely take the time to understand an opponent’s arguments. We’re all guilty of tearing down straw men, intentionally misrepresenting an opponent’s proposition to avoid dealing with their argument. And unfortunately, social media deliberately distances us from contrary opinions and makes true engagement all the more difficult.

To live humbly in this way (and consistently), we must make it a priority to read charitably and widely. This means taking seriously the ideas presented by those we disagree with, assessing those ideas to the best of our abilities, and opening ourselves up to the possibility that they might change our minds. This includes looking for sources and opinions outside of our intellectual circles and purposefully filling our feeds with those we might disagree with.

Any belief worth holding must be able to stand up to rigorous testing. And reading across the aisle puts our ideas in the crossfire. If our ideas can’t survive the fire, they weren’t worth holding onto in the first place.

Ultimately, self-delusion is the product of pride. When we cannot see past ourselves, we are unable to see one another. In a world that rewards and encourages this delusion, it is incumbent on us to cultivate humility. Pride is what makes discourse impossible, and our digital lives often serve it — not our relationships, not our neighbors. Cultivating intellectual humility is the only way forward in a polarized and divided world, and this is the life we are called to live.