In the year 1720, a man returned home from two months’ travel to find his wife dead, and not only dead, but buried already. Naturally, this revelation devastated him. In apparent response, J.S. Bach created a body of music that seems to lean into loss, embody its haunt and anguish, and somehow in this dark reality, remake his craft and give witness to a world far beyond his own.

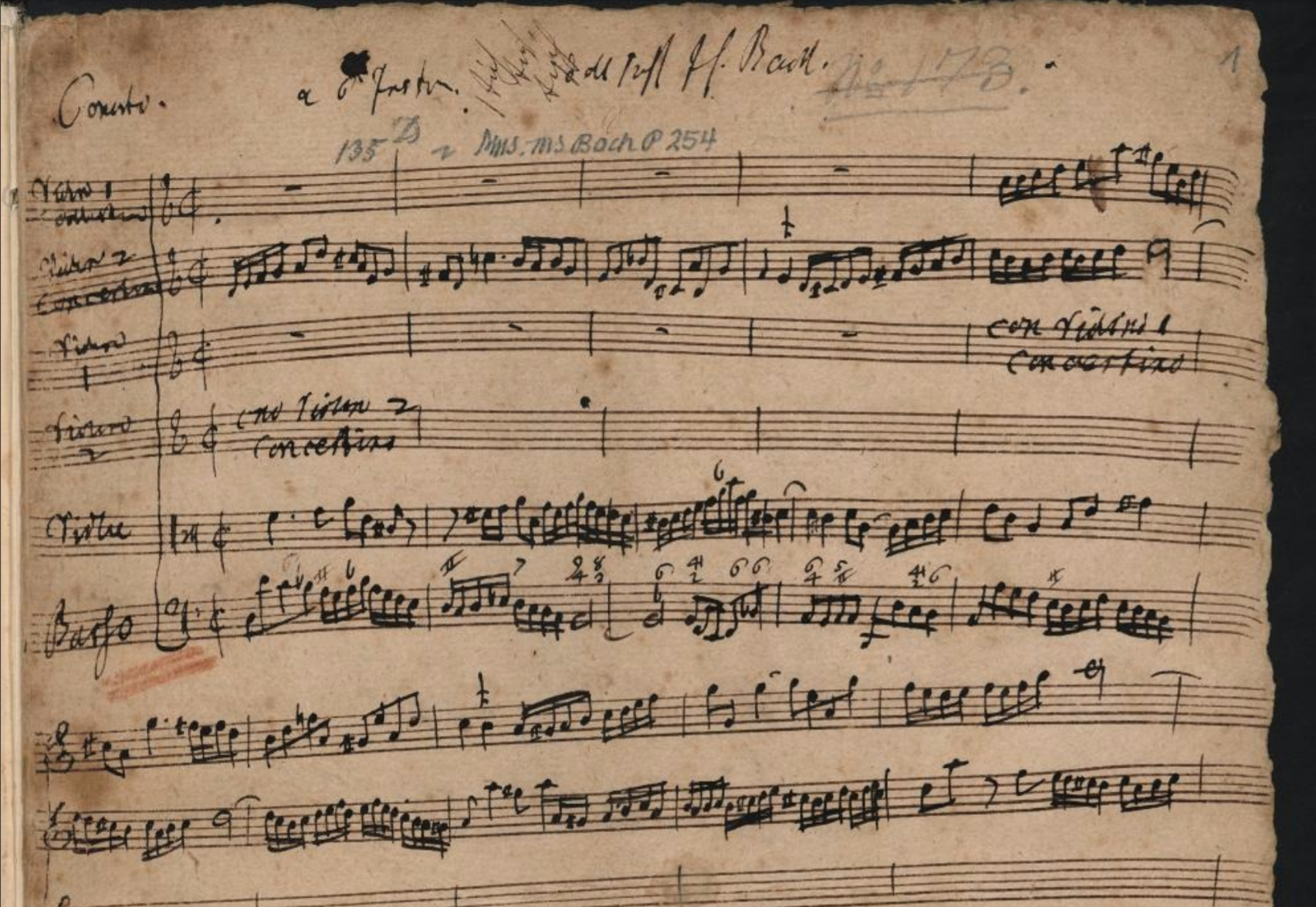

“The extraordinary Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin, which he wrote that year, are thought to be in tribute to [his late wife],” explains Guy Jones, who works with classical music curation at Apple Music. “A note on the title page of the manuscript reading ‘se solo,’ when read as German rather than Italian words, would mean, ‘You are alone.’”

“The music itself is staggering. Not only did it establish and push the boundaries of what a solo violin technically was capable of but they later became something of a sacred text for violinists and composers alike. It’s that combination, again, of head and heart, technical genius and emotional expression,” says Jones, reflecting on Bach’s response to his wife’s death.

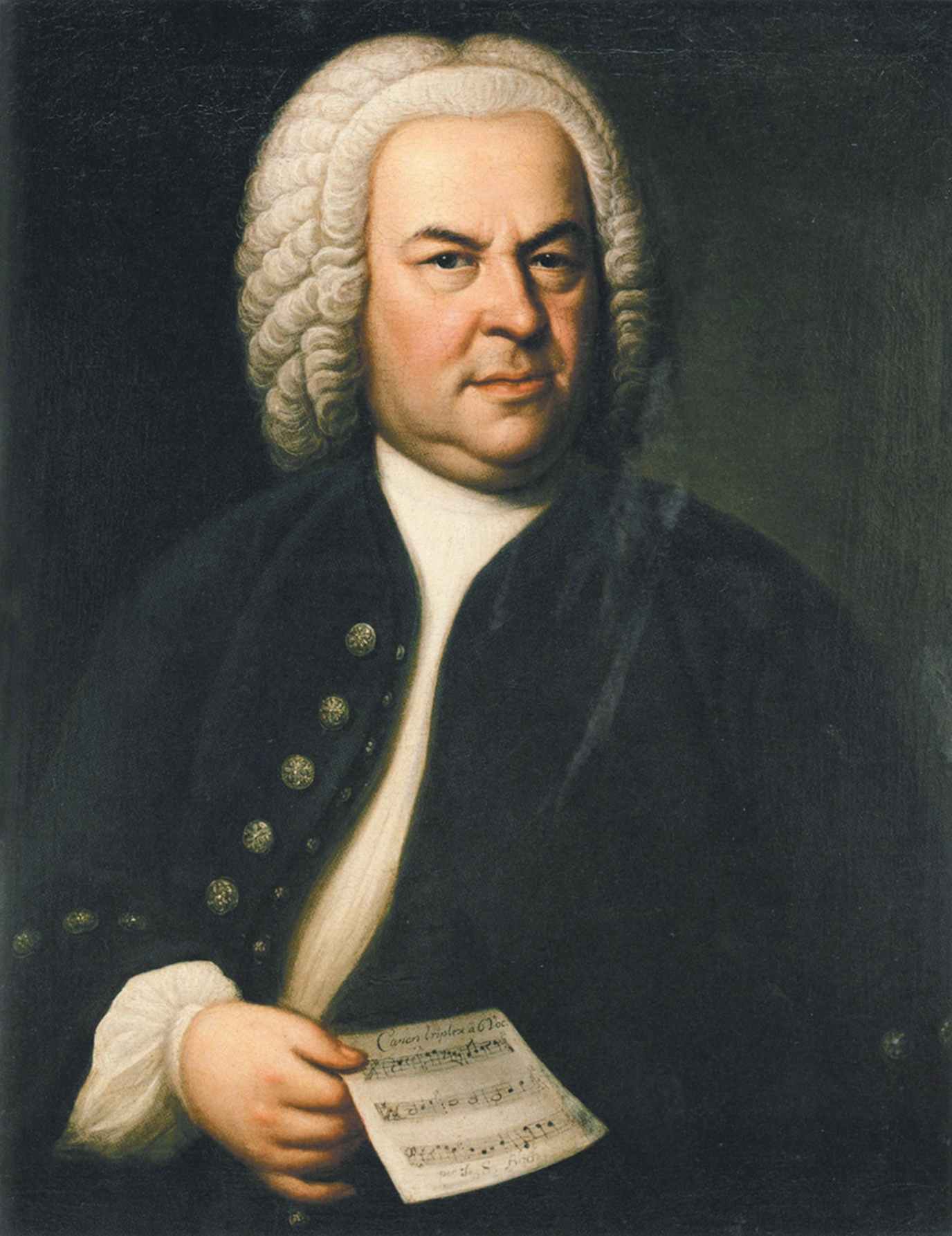

In the traffic-jammed space between my house and my doctor’s office, I’ve been listening intermittently to Jones’ podcast the Story of Classical. If you haven’t listened, you can probably guess the show gives a flyover history of classical music, in this case a song-laced timeline from the baroque period to today. Jones’ treatment of the baroque period centers around Bach. The iconic composer, who made music in the first half of the 18th century, worked as a church musician. In that context, he wrote a seam-pulling range of music that far outlasted Sunday services and vespers, that shaped a whole era of music, and that, today in spring 2023, still leaves people in wonder.

I never really wondered at Bach, though. You see, I grew up in a church-going, musical family. To me, a person like Bach, doing the things Bach did and doing them in and around the church, seemed not unusual. And as musical as our family is, I’m the least of that talent pool, and I’m certainly not skilled enough to identify immediately when this or that piece of music transcends one or another. In my mind, to some degree, Bach was Bach, just like Gershwin was Gershwin and MXPX was MXPX. In college, though, I spent my fine arts requirements on music history courses, and then I did start to recognize the strata of musical accomplishment. Later, in the mid-2010s when I edited a culture magazine (note: our coverage was of, um, not classical music), I developed a habit of asking why certain musicians or bands last longer than others, why some sound just right for the moment and others sound somehow less bound by time. And I did come to wonder at the fact that, in the last 400 years of music, many of us could only name 20 or so artists one could consider important, and if you can only name two or three, one is almost certainly Bach.

Not until just a few weeks ago did I realize, while listening to the Story of Classical segment about Bach, that I haven’t sufficiently understood Bach as a master composer and church musician, indivisibility. Yes, the institutional church represented basically the sole economic engine of 18th century arts. And, yes, like everyone before and after, Bach inhabited his time and its sentiments. Yet we hear in this composer a witness of something beyond these factors.

Bach’s witness is one that, in some cases, moves outside analytic categories and confounds existential expectations. I keep thinking about this one moment in the podcast, just a minute or two long, that evokes nothing if not wonder: Jones, who seems friendly to, but not necessarily familiar with church, names two Bach experts, neither of whom share the composer’s beliefs, whose deep engagement with Bach’s work presses on them. Here’s a transcription:

Despite being written very much in a religious, specifically Lutheran, tradition, many musicians and academics alike agree that [Bach’s music] is either so powerful that it somehow transcends its religious context and becomes something more universally human, or even prompts questions regarding your own faith.

Michael Marissen, author of the book, Bach and God, describes himself as an agnostic, and yet he says Bach never allows him to be a “comfortable agnostic.” John Eliot Gardiner, one of the finest Bach conductors alive today echoes the sentiment: “It’s irresistible in its persuasiveness. I cannot deny that even if my logical mind says, ‘No,’ my soul, my spirit says this could only have come from somebody who has a totally credible and believable sense of the godhead and the futility of human existence.’”

Sure, great compositions often elicit emotional, even spiritual responses. But what keeps playing in my imagination is the existential and theological nature of these reflections. By confessed unbelievers. These comments from Marissen and Gardiner aren’t relegated to the churchy reality of the 18th-century arts scene. They’re not even respectful nods to Bach’s sincere personal belief. No, these men seem to say the force, the spirit, of Bach’s work overwhelms them with a kind of beauty that can’t be explained by notes in black and white.

I can hardly comprehend the notion that the effect of someone’s work could be so profound — not in declaration, but in passion and quality and creativity — that it rattles beliefs and uncurtains a world where the divine is, and is at work. In his biography of Bach, Gardiner uses “the castle of heaven” as a description of and a metaphorical context for Bach’s output and influence. I might prefer instead to think of a garden, where the work happens amid the tragedy of death, yet where occasional blossoms make tropistic signals to a world where, once again, the human and the divine will stroll. Because while fantastically Bach’s music reveals part of the divine, I think it also reveals some of what it means to be human.

Perhaps quintessentially human. In his brief biography of Bach, Rich Marschall recounts how, in 1977 as researchers prepared to send a probe into space with artifacts from earth, one prominent voice suggested Bach’s complete works, but determined “that would be boasting.” Fair, Bach’s genius likely will remain inimitable. Yet that can’t mean — it shouldn’t mean — that people like you and me don’t try to create, to make, to inhabit our worlds like Bach did his.

What that means for electricians and accountants, students and pastors, people who care for children and people who write words, I don’t exactly know. I do know that each of our lives contains realities, some dark, into which we should lean while we work and, maybe, give witness to the world far beyond.