Stories of Her Life

1973

The Sign of the Chrysanthemum

Paterson’s first novel, set in 12th-century Japan, tells the story of an orphan in search of his father. She got the idea from her adopted daughter’s questions about her own biological mother.

1974

Of Nightingales That Weep

1976

The Master Puppeteer

(National Book Award)

1977

Bridge to Terabithia

(Newbery Medal)

If you know just one book by Paterson, it’s this one. The beloved, controversial, and celebrated novel goes headfirst into the toughest experiences and questions a child could face.

1978

The Great Gilly Hopkins

(National Book Award)

Right on the heels of Bridge, Paterson wrote her second-most recognizable story. This one tells the story of a rambunctious orphan and the foster mom, Ms. Trotter, who cares for her.

1980

Jacob Have I Loved

(Newbery Medal)

Asked about her best work, Paterson names Jacob as her proudest work. The story follows sisters Sara Louise and Caroline Bradshaw, and Louise’s attempt to escape Caroline’s shadow.

1983

Rebels of the Heavenly Kingdom

1985

Come Sing,

Jimmy Jo

1988

Park’s Quest

1990

The Tale of the Mandarin Ducks

1991

Lyddie

1991

The Smallest Cow in the World

1992

The King’s Equal

A somewhat lesser-known Paterson story, The King’s Equal tells the story of a king so self-absorbed that he gets cursed for his narcissism — until he is able to identify his equal in another.

1994

Flip-Flop Girl

1995

Jip, His Story

1995

A Midnight Clear:

Stories for the Christmas Season

1996

The Angel and the Donkey

1997

Marvin’s Best Christmas Present Ever

1997

The Field of the Dogs

1998

Parzival:

The Quest of the Grail Knight

1998

Celia and the Sweet, Sweet Water

1999

Preacher’s Boy

2000

The Wide-Awake Princess

2001

Marvin One Too Many

2002

The Same Stuff as Stars

2004

Blueberries for the Queen

2006

Bread and Roses, Too

2009

The Day of the Pelican

2011

Brother Sun, Sister Moon:

Saint Francis of Assisi’s Canticle

of the Creatures

St. Francis composed his Canticle of Creatures, a song of praise, in the first half of the 13th century. In the early 21st century, Paterson re-imagined it as a children’s book.

2011

The Flint Heart

2017

My Brigadista Year

2019

The Night of His Birth

2021

Birdie’s Bargain

“My favorite professor in Richmond had stopped me in the hall one day and asked if I had thought of becoming a writer. I was kind of horrified at the thought. I wouldn’t want to add another mediocre writer to the world. She said, ‘Maybe that is what God is calling you to be.’ And it took me a long time to realize if I didn’t dare to be mediocre, I’d never be a writer at all,” she says.

“That’s what Chesterton said: If a thing is worth doing, it’s worth doing badly,” I reply.

“I was terrified of being a mediocre writer. I never think of myself as a particularly brave person, but I thought, ‘By golly, you are brave.’”

My friend and I sit at a small table in the corner of Capitol Grounds, a solid second-wave coffee shop two and a half blocks from the Vermont State House in Montpelier. We drink the morning brew and exchange bewilderment about the iced weather. We’d scheduled our trip to the Green Mountain State for late April in hopes of finding the state’s mountains green, but winter evidently lingers here — at least in late April 2024.

For being a state capital, Montpelier isn’t an easy place to get to, not compared to Austin or Atlanta or Sacramento. We flew into Boston yesterday, and drove up Interstate 89 nearly to Canada. Even without the turned leaves that make Vermont a pilgrimage destination in autumn, you can see the appeal. This tiny town of about 8,000 exudes a Norman Rockwell energy, with farmhouse-style houses shelved up the hillsides, nearby covered bridges, main street shops and restaurants like Capitol Grounds, and a certain granola air that guarantees enthusiastic farmers’ marketing. Why a writer would retire here at least makes sense.

We start talking about the kinds of stories we share with our children, and which we delay. Both of us are fathers, you see, and artists to some degree. In an hour or so, we’ll drive four or five minutes up to the apartment of beaucoup-award-winning novelist Katherine Paterson, and as we prepare for what will be an hours-long interview and photo session, her book Bridge to Terabithia shapes our conversation. In all art, but especially with the forms meant for children, questions persist about whether works should carry a message and who exactly bears a responsibility for it. Practically, if you’re a Christian writer, are you obligated to evangelize or instruct in your writing? Paterson has given her answer to that question.

For millions of people, Paterson’s best-known book contains a profoundly true story. Yet, as in life, the truth arrives raw and uncomfortably, and for nearly 50 years parents and educators have taken umbrage with the children’s novel. This contrast, it seems to me, represents Paterson — or at least exposes what makes her interesting. That’s why we’re in Montpelier, not to talk about just one story, but to probe a wider story of a missionary, pastor’s wife, and mother of four whose prolific and acclaimed literary work makes her one of America’s most celebrated writers.

Along with Bridge to Terabithia, Paterson authored more than a dozen other books, including children’s novels, picture books, and a few works of nonfiction. Stories like Bridge and The Great Gilly Hopkins have been adapted into movies (remember Kathy Bates as Ms. Trotter?). Paterson more than once earned the most prestigious awards in her space, the National Book Award and the Newbery Medal. And according to the internet, she is one of four people ever to win both major international awards — the Hans Christian Andersen Award for Writing and the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award from the Swedish Arts Council. Her full list of awards goes long enough to make it boring.

As much as her life now basically represents American literature, she’s equally given to the church. She arrived in this world as a missionary child, she attended seminary, and she married a pastor. For some 50 years, she ministered in churches from Maryland to Virginia to just about eight miles from here in Barre, Vermont, where her husband pastored First Presbyterian Church. The church, we learned, with the green building. Paterson still attends First Presbyterian, if she can get a ride.

For most of her life in Vermont, Paterson lived in a 1830s farmhouse right in Barre. But for the last 10 years or so, following the death of her husband of 51 years, she’s been in a Montpelier apartment. According to the internet, the term for this kind of place is “senior living community,” which I guess means it’s less clinical than an “assisted living” place and less vocational than a retirement home. I once heard Paterson refer to it as the “old folks’ home.” We’re supposed to meet her at 10 a.m., but we’re too early and just sit in the parking lot for a while.

The low-profile, white-sided building sits on the top of a hill more or less looking down on neighborhoods below. When we do walk in and find no one at the front desk, a man asks where we’re headed. We tell him the apartment number, and he says without hesitating, “Oh, Katherine Paterson.” So either people here generally know each others’ addresses, or maybe this guy and Paterson happen to be friends. Or maybe the apartment number means less than the recording and camera equipment we’re hauling. After all, when a crew from MSNBC showed up the week before, it too was looking for Paterson.

*

Just after 10 a.m., we’re sitting in Paterson’s ground-floor apartment in a large room that looks about like you’d expect a 91-year-old’s to look like. The furniture, mainly stained wood, is an eclectic mix of mid-century and ’80s styles, some pieces tired and others I think could fit a grandmillennial decor. The walls and surfaces hold up photos, very old and very new. The dominant texture is fabric. Like almost all apartments, hers has only one exterior wall, and that wall frames 17 windows — I don’t count the windows, but she pipes in with the total count — looking out onto some would-be green space.

Paterson stands not very tall, her full face framed by gray — not silver, not white — hair. Her eyes are slightly hooded, but they shine when she laughs, which she does frequently and deeply. Her personality seems clear, and she’s warm and welcoming. She moves with the gait of someone 10 years younger. Surprisingly, she initially appears more fidgety about the interview than the photographs, for which she poses and ignores with professional-grade confidence.

We sit more or less facing each other, me with a legal pad in my lap, and we start at the beginning.

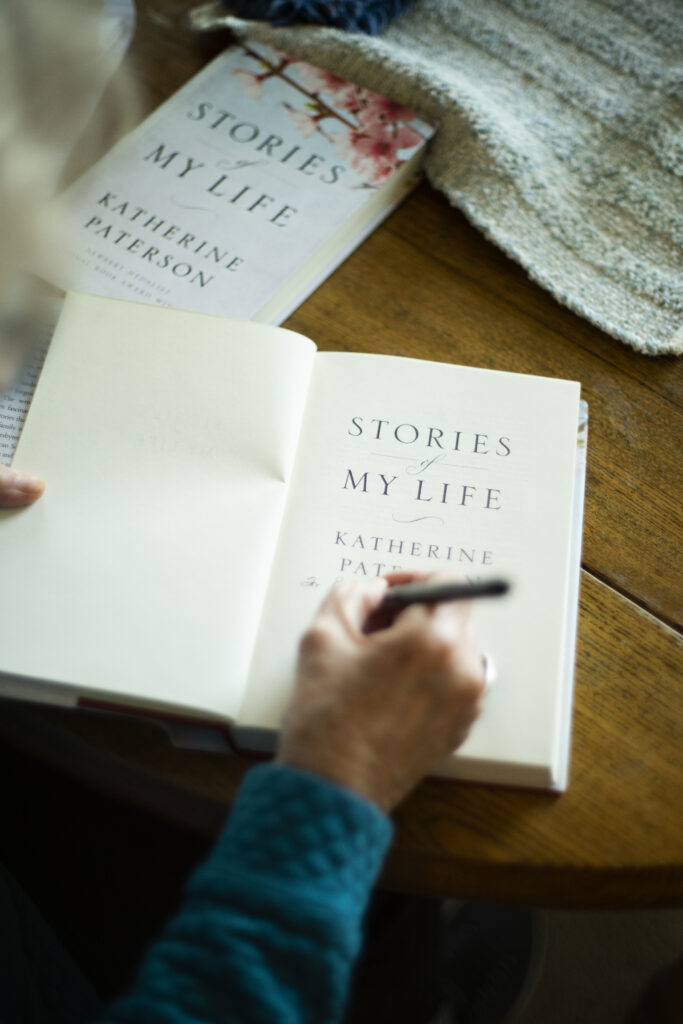

Paterson’s early life Etch A Sketches from place to place like a military family’s. In the back of her 2022 memoir, Stories of My Life, she includes a multipage timeline to keep it all straight. The overview goes like this: Katherine Womeldorf was born in Qing Jiang, China, in 1932, to parents Mary and George, who were Protestant missionaries. Once Japan invaded China in 1937, the family moved back and forth between China and the United States until it became clear by 1946 that they would not be able to return to China. In 1950, Katherine went off to college, then seminary in 1955. Once she graduated in ’57, like her parents before her, she wanted to go to China, but also like her parents, geopolitics wouldn’t allow it.

A friend who was Japanese encouraged her to “give Japanese people a chance,” which didn’t appeal to a woman who had lost her childhood home to an invasion by the Japanese.

“I hated the Japanese,” she told me, “because they were the people who bombed and occupied and frightened us. But I loved her.” She asked her mission board — the Presbyterian Church U.S. Board of World Missions — for an assignment in Japan, and then spent four years working for 11 pastors in rural Japan, motorcycling between the villages to help the churches with everything from teaching to preaching to administration. The time was, according to Paterson, transformative.

“I really believe that there’s nothing as wonderful as being loved by people you thought you hated,” she said.

Paterson returned to the States in 1961 to do more seminary work. And while at Union Theological Seminary in New York, she met a man who pastored a church in Buffalo — a single man who pastored a church in Buffalo. That was February 1962, and Katherine married John Paterson in July.

Over the course of their 51 years together, the Patersons had four children: Lin, John, David, and Mary. The first two came the same year, 1964, John by birth and Lin by adoption. This same year, according to Paterson, she began thinking seriously about what her seminary professor said, about whether she might be brave enough to write.

“I tried some poems,” she says. “I sold one short story, but the little Roman Catholic magazine went out of business the next month. I sold a poem to another Roman Catholic magazine, then it died before publishing my poem. It was seven years of just writing this, that, and the other, trying to find out what it was I did.”

By then, the Patersons lived in Maryland, and a woman in the church invited Katherine to take a writing course with her. Motivated both by the topic and the chance to spend the occasional evening outside her home, Paterson joined the class. She and her friend enjoyed their experience enough that they signed up for the next offering — a class about writing for children.

*

Bridge to Terabithia tells the story of fifth-grader Jess Aarons who becomes friends with his new neighbor, Leslie Burke. Leslie’s family is affluent and connected to the outside worlds of politics and the news; Jess comes from a large, poor family whose limits and low-grade suffering leave him angry and eager to prove himself. The two kids, both outsiders at their school, create a play world for themselves, an imaginary kingdom in an unimaginary deep part of the woods between their houses. To get to the kingdom, which Leslie imagines as their own Narnia, the kids have to jump a stream with the help of a rope. The place on the other side, they call Terabithia.

Leslie plays the tomboy, and Jess hides a talent for art that he only shares with Leslie. Jess falls in love with his music teacher who at least somewhat kindles his interest. And then, one day, Leslie falls into the stream when Jess isn’t there, and she drowns. This boils in Jess the anger he harbors against his place in the world, against himself for enjoying something girly, and against God for making his family poor and letting his best friend die.

Bridge to Terabithia explodes with emotion, and since its release in 1977, readers have reacted emotively, too. It won in 1978 the Newbery Medal, and since its debut it’s sold around 8 million copies, which make it one of the most read children’s stories in the English language, only a tier or two below household names like the Chronicles of Narnia or the Percy Jackson books. Bridge has twice been adapted for the screen: a 1985 TV movie on PBS and a 2007 feature film.

For the last 47 years, articles and articles, even a documentary, have explored the impact of Bridge to Terabithia. I even read one poll from 2012 in which respondents voted Paterson’s breakout as a top 10 children’s novel of all time. Paterson tells me she can’t remember for sure, and reliable information is hard to come by, but she estimates the first printing at 7,000 copies.

Correspondingly, the book often meets concerned parents (and administrative types), and it appears at number eight on the American Library Association’s 100 Most Frequently Challenged Books (1990 to 2000). That crew from MSNBC that preceded us? They came to interview Paterson for a news segment about banned books.

“If a book has any power, it has the power to offend,” Paterson says when I ask about Bridge’s seemingly persistent controversy. “And most of us don’t want to write books that have no power, but you have to take the risk that it’s going to offend somebody.”

I should note that the conversation around banning books in 2023 and ’24 carries a different flavor than many of the banning efforts that preceded it. The function remains the same, of course, but the censorship debates of past decades happened in a decidedly less partisan America.

For the book’s 50th anniversary in 2027, its publisher will release a commemorative edition of Bridge to Terabithia, and Paterson is writing an introduction for it, including reflections on why it’s so often challenged.

“A few people say it’s because of the death of a child, and I’ve got to believe that’s what is behind most of them,” she says. “We just can’t dare to think about the death of a child. Thousands of children are dying every single day in this world, but they’re over there. Our children can’t die.

“But they do.”

Some of you may know already that Paterson drew inspiration for Bridge from the death of her son David’s best friend, Lisa Hill. In August 1974, 9-year-old Lisa was struck by lightning and killed. Paterson watched David face what Jess faces, and in many ways the story of Jess Aarons is the story of David Paterson.

When the ’07 film version of Bridge — for which David Paterson wrote the screenplay — outperformed opening weekend expectations, executives from Disney asked for a sequel.

“I told them, ‘No amount of money will buy you a sequel,’” Paterson says. I press a little about why, since she’s already said that she’s more than open to trying ideas that others have.

“It’s complete in itself,” she says. “I was just horrified to think what they might try to do with it. In David’s mind, and I think also in my mind, [the story is] really a memorial to Lisa Hill. Her family has been so wonderful and gracious with what we’ve done with their child’s life and death. I’m going to leave it at that.”

*

Bridge landed right in the middle of a wildly successful run for Paterson. For four different books she wrote between 1976 and 1980, she won two Newbery Medals and two National Book Awards: The Master Puppeteer (1977 National Book Award), Bridge (1978 Newbery Medal), The Great Gilly Hopkins (1979 National Book Award), and Jacob, Have I Loved (1981 Newbery Medal). These books established Paterson as a literary force, and put her work in nearly every library in the country. The Great Gilly Hopkins became a movie in 2015, one with a major Hollywood cast including Kathy Bates, Glenn Close, Octavia Spencer, and Julia Stiles. All things not exactly indicative of a mediocre writer.

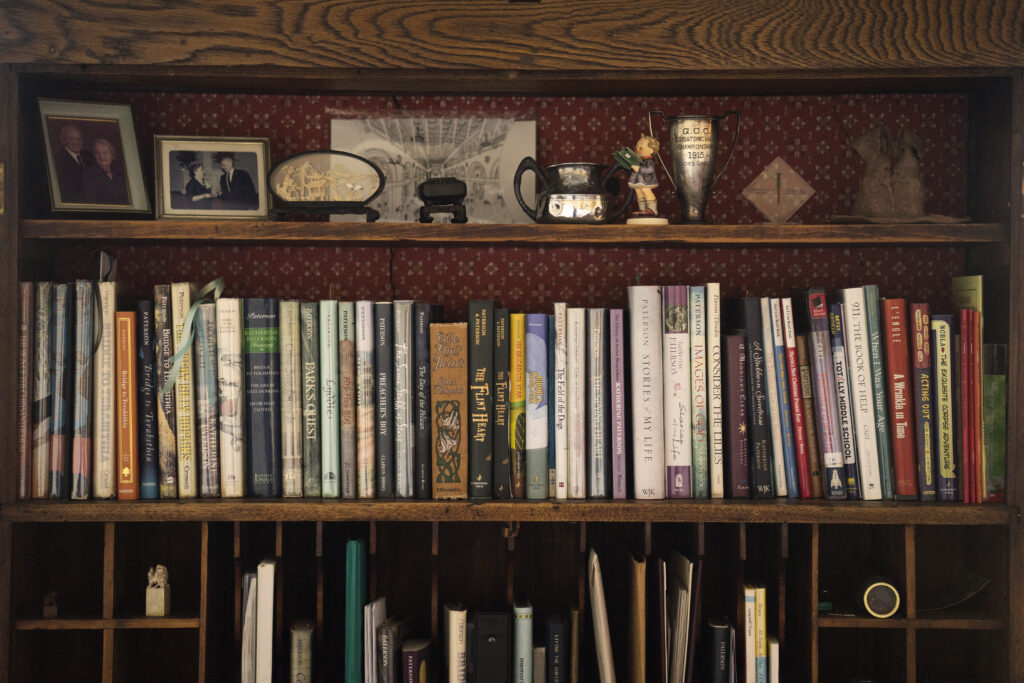

After lunch, pizza from a place called Positive Pie directly across the street from Capitol Grounds, we wander through a bedroom Paterson uses as a study and a kind of sunroom where she keeps her awards, her less organized books — which means the books she actually reads — and Bibles. We talk at random about books, these ones and others. She’s part of a book club led by a woman whose taste Paterson admires, and those books weigh down one of the sunroom shelves.

After lunch, pizza from a place called Positive Pie directly across the street from Capitol Grounds, we wander through a bedroom Paterson uses as a study and a kind of sunroom where she keeps her awards, her less organized books — which means the books she actually reads — and Bibles. We talk at random about books, these ones and others. She’s part of a book club led by a woman whose taste Paterson admires, and those books weigh down one of the sunroom shelves.

We stand for probably 10 minutes by the shelf, more or less trading reading recommendations. She thinks I should read a book called All the Beauty in the World: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Me. And a graphic novel by the late John Lewis, a book awarded the National Book Award one of the years Paterson sat on the judging committee. Our conversation feels natural and easy, yet I know I’m standing with a legend of American letters, one whose successes and age seems only to increase her excitement about books and writing.

I try to keep up, but I can barely mention a book she hasn’t read. We talk a lot about Marilynne Robinson, especially her novel Gilead, which Paterson considers “one of the greatest novels ever written.” Min Jin Lee’s Pachinko. All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr, as well as his latest book Cloud Cuckoo Land. Eventually, I bring up a book she doesn’t know, a novel by Wendell Berry called Hannah Coulter, and Paterson asks me to write down the recommendation so she can find and read it. She reminds me of this request twice before the afternoon ends.

Over the course of talking about Paterson’s writing life, one name comes up more than any other: Virginia Buckley.

Back up to Paterson’s first novel, The Sign of the Chrysanthemum. The editor who initially acquired it for Thomas Y. Crowell in 1971 ended up passing it off to Buckley, a young editor who was just coming off maternity leave and didn’t have anything on her desk. That assignment turned into a 40-year professional relationship that included 16 of Paterson’s 18 books and lasted right up until Buckley died in 2020. It’s Buckley who Paterson credits with her sustained output — the fact that she did not, as yet, go the way common to older, acclaimed authors whose clout results in timid editing and poorer books.

“I was very, very blessed to have Virginia,” Paterson says. “She would never let me get away with something. She wasn’t impressed by me.”

The other editor of almost every Paterson book was another Paterson. Her husband read all of her first drafts.

“He would always be the first reader, and I’d give writing to him when I had a draft that I thought I could stand,” she says. “If he came out of the room where he’d been reading and he wasn’t crying, then I knew I was in trouble.”

What made John Paterson a good editor, according to Paterson, was that he could ask the right questions: “Virginia never would tell me what to do, but she could ask the questions that I would have to solve. And John was very much the same way.”

She tells the story of writing Park’s Quest, a 1988 novel of a boy trying to learn about his father who died in the Vietnam War, the main character of which accidentally shoots a crow with a gun. After reading the relevant passage, John Paterson relayed to his wife that anyone would be able to tell she never shot a gun. She went to a gun store to learn what she could about shooting guns.

That kind of research activity isn’t unique to Paterson, of course, but it does demonstrate the seriousness with which she takes her work. When writing Jacob, Have I Loved, she traveled to Virginia to “touch the ground and smell the air.” She visited China while researching another book. She invested time at a puppetry theater while writing The Master Puppeteer.

She says, “That’s the kind of thing you have to do if you’re going to do it right.”

Paterson’s effort to do it right shows. And given that she was her most prolific at a time when she had four children in the house, she naturally receives questions all the time about how she could accomplish what she did, a question that assumes a kind of scheduling that provides some kind of productivity bronze bullet. She laughs at the idea.

“I’ve been writing around interruptions all my life,” she says. “I started writing when I had four tiny children. I realized very early on that when you’re writing, you don’t hear things. And if you’re a mother of four tiny children, you have to be able to hear and you have to not be distracted by your work when you should be paying attention to your children. So I made the point not to write when there was anybody around who might need attention. … [But] your subconscious is always working, and when you have five minutes, you can write.

“People say, ‘I’m going to write a book as soon as I have time,’ but of course they don’t have time. No, what you need is nerve, not time. You’ll find time if you have the nerve.”

*

Actually, my first encounter with Katherine Paterson didn’t happen as a child. Like a lot of people, I was aware of Bridge to Terabithia and The Great Gilly Hopkins and some other of her titles, but that’s about it. My first encounter was just a couple years ago hearing her speak at the HopeWords Writers’ Conference in West Virginia.

There’s a long, long conversation, one that has a particular shade in Christian circles, about the form of art and the content of art. In this case of writing children’s stories, the question basically relates to the extent to which content exists outside of form. For example, could a poem be straightened out into prose and retain its meaning, or is the form somehow part of the meaning?

During her talk at HopeWords, she wrestled with the same question that many others have been trying to figure out: How do you make sense of Katherine Paterson the missionary, seminarian, and pastor’s wife with Katherine Paterson the prolific author of a book famous for its heavy theme and irreverent questioning of God? Or, what do you do with her content and form?

She proposed two paths writers who are Christians can take. Either messengers or spies. It goes like this: When Moses and the children of Israel are on the banks of the Jordan River, Moses sends 12 spies into Canaan and only two — Joshua and Caleb — returned seeing the difficult reality but confident that God’s plan would prevail.

“I want to be a spy like Joshua and Caleb,” Paterson said according to a transcript of her talk. “I’ve crossed the Jordan and tangled with a few giants, but I want to say to those who are hesitating to cross, the promised land is worth possessing, and we are not alone.”

She seemed to say there is a place for proclamation, for preaching, and for prophecy. And there is a place to be as wise as serpents. In the Gospels, we see even Jesus implore people not to tell anyone what he has done. There is a place for preachers and a place for novelists.

“All of my adult years, I’ve done a good bit of preaching and teaching the Scriptures,” she said in her talk. “I love being a messenger of the good news. So, again, Katherine, Why when writing fiction do you think of yourself as a spy rather than a messenger? Most adults and even a few children assume that when you write for children, every book you write has a message for the reader. I get that question every time I speak about my books. What message do you want children to get from this book? And I invariably answer, ‘That’s not my job.’”

This fits in a long conversation of Christians making art — making anything, I’d think — and wondering about what they make. If you’re doing your work like a Christian, should the fruit of that work always be evangelism? Is it to truth-tell, to paint the world as it is, flaws and all? Is it, to get to the question of form and content, a question of decorating a message? She continued:

My job is to write the best, the truest story I can. It is the reader’s privilege to decide what they want to take away from their reading. My book may hold a message for them, it may not, but that’s the reader’s choice. It’s the reader’s privilege to decide what this book means for their life. …

A story does not ask for decision. Instead it asks for identification, which is how transformation begins. Now just think for a minute about the story we call the parable of the prodigal son. Do you identify with the wayward boy, his older righteous brother, or even, on rare occasions, with the loving Father? Jesus lets us choose. Identifying with any of the three may well be transforming.

The thing about doing the job of a spy, it takes bravery.