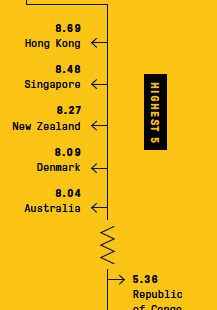

The most recent Economic Freedom of the World Report, published by the Fraser Institute, numbers are in, and the news isn’t good. Global economic freedom around the world has declined from a global overall average score of 7.0 to 6.84. The economists who develop the research claim that this wipes out about 10 years of economic progress, and this is bad for everyone. This is particularly for the world’s poorest human beings.

The concept of economic freedom, and attempts to measure it empirically, comes from Nobel laureate economist Milton Friedman in the 1970s. He wanted a measure of prosperity to inform helpful policies and institutions. The report scores economic freedom on a scale of zero to 10, where zero indicates that there is no economic freedom and 10 indicates perfect economic freedom. There are five areas of economic freedom measured: sound currency, the size and scope of regulation, legal system and private property rights, the size of government relative to the size of the economy, and the freedom to trade internationally. Combined, these give us a picture of the institutional infrastructure of society.

The Economic Freedom of the World Report is published annually, and the data is lagged by two years, so the 2022 index is measuring data for 2020, so this is the first year we have a full year of COVID-19 data included in the index.

In societies where economic freedom is high, people experience the benefits of commercial exchange that fosters societal trust. Personal freedom and private property rights are secure, and this fosters entrepreneurship and innovation. And by empowering human creativity, countries with high economic freedom provide the best chance for people to gain a permanent escape from poverty. And because economic growth is the only way permanently to escape poverty, the freedoms that engender it are moral imperatives.

Where regulatory burdens are overly oppressive, it will be difficult for people to start businesses and make investments. Overly restrictive regulations combined with a lack of private property rights and an independent court system mean that people often lack access to capital.

Corruption and political oppression mean that the worst get to the top and stay on top, and these societies are characterized by a lack of income mobility and economic decline. It’s not surprising then that the 2022 index scores Venezuela (3.32) as the worst-performing economy in the world for which we have data.

Some of these countries have been persistently stuck in poverty and oppression, and some have collapsed, once rich and free and now poor and oppressed, like Argentina and Venezuela. These are man-made tragedies, fully avoidable but redeemable. This is the good news: Societies and economies can collapse, but they can also rebuild. We know that all countries can obtain high levels of economic freedom and abundance and experience the personal well-being that results.

The Economic Freedom of the World Index provides a roadmap to inform our understanding of how we can make improvements in the direction of free societies and free people.

The benefits are materially egalitarian. What only the very rich had access to 20 years ago is commonplace today: Cell phones, laptops, teeth-whitening toothpaste, and flat-screen TVs are commonplace in most American households today. The reason is that the benefits of economic freedom, which are innovation fueled by entrepreneurship, are received by everyone, not just the rich. Yes, it’s the rich who first consume these innovations, but the progressive cheapening of goods and services is what results. Economist Mark Perry demonstrates that TVs are about 97 percent cheaper today than they were in 2000, and computer software is about 72 percent cheaper. That is because of innovations that bring those products to the masses. It’s no longer the rich and famous who can have access; we all can.

On the contrary, in the U.S., hospital services are 220 percent more expensive and childcare is up 115 percent during the same period of time. The difference is a key component of economic freedom: the level and scope of regulation. Hospitals and daycare services are some of the most regulated aspects of the U.S. economy, which means less innovation and consistently rising prices. This has an inegalitarian outcome because those higher prices most hurt the lowest-income people among us.

If we want to help the poorest in society, whether that’s in the U.S. or anywhere in the world, we must advance economic growth by fostering more economic freedom. We’ve been heading backward, but the good news is that we can reverse course.