“I’m feeling so much anxiety I don’t know where to begin.”

“To be honest, I’ve been freaking out the past few months and in hindsight can’t believe how foolish I was to do this.”

“I am extremely embarrassed to write this. I am in a very, very tough financial spot right now. I have about $34,381.67 in credit card debt spread across 9 cards. 2 of them have been closed by the creditors.”

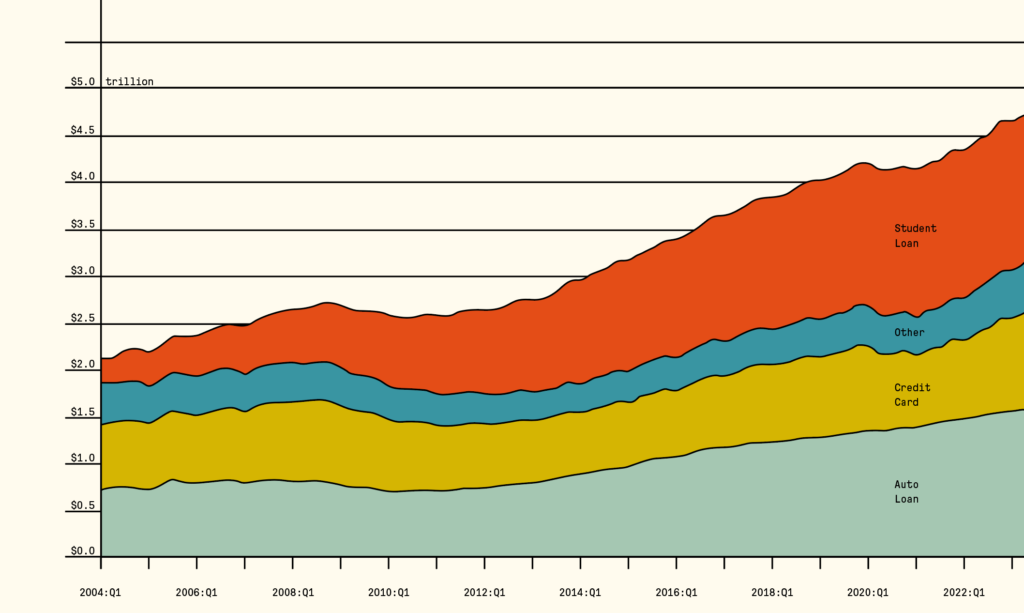

These quotes from Reddit’s personal finance thread illustrate debt’s psychological cost more viscerally than numbers do. Even though the numbers are plenty bad. U.S. household debt grew by $16 billion in the second quarter of 2023, with large increases in credit card balances, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit.

One of the most classic, accurate, and unhelpful answers in economics is “it depends.” Could this be the answer for the best way to get out of debt?

For someone seeking to get out of debt, there are two prominent strategies. If one is more likely to succeed, it would be the obvious choice.

Economic theory suggests that the best way to pay down debt is minimizing interest charges. Rank all debt accounts in order of decreasing interest rates (highest interest rate first). Pay minimum payments on all accounts, but put extra money toward the one with the highest interest rate. After paying the first account off, use the money that had been going to it to tackle the next account. This is sometimes called the “debt avalanche.” The rationale: Consumers save money by paying the costliest debt first, making successfully eliminating debt more likely. Simply put, debt is a math problem.

Some personal finance advisers, most notably Dave Ramsey, advocate a different approach: the “debt snowball.” Rank all debt accounts in order of increasing account balances (smallest balance first). Pay minimum payments on all accounts, but put extra money toward the one with the smallest balance. After paying the first account off, use the money that had been going to it to tackle the next account. The rationale: Small wins encourage perseverance and foster better habits, making successfully eliminating debt more likely. Simply put, debt is a human behavior problem.

For the typical indebted consumer, the two approaches actually produce similar results. We’ll see these results, consider why we should expect similar results, and evaluate the assumptions behind these strategies. Ultimately, this analysis reminds us that knowledge, a work in progress, requires humility.

A Tale of Surprising Similarity

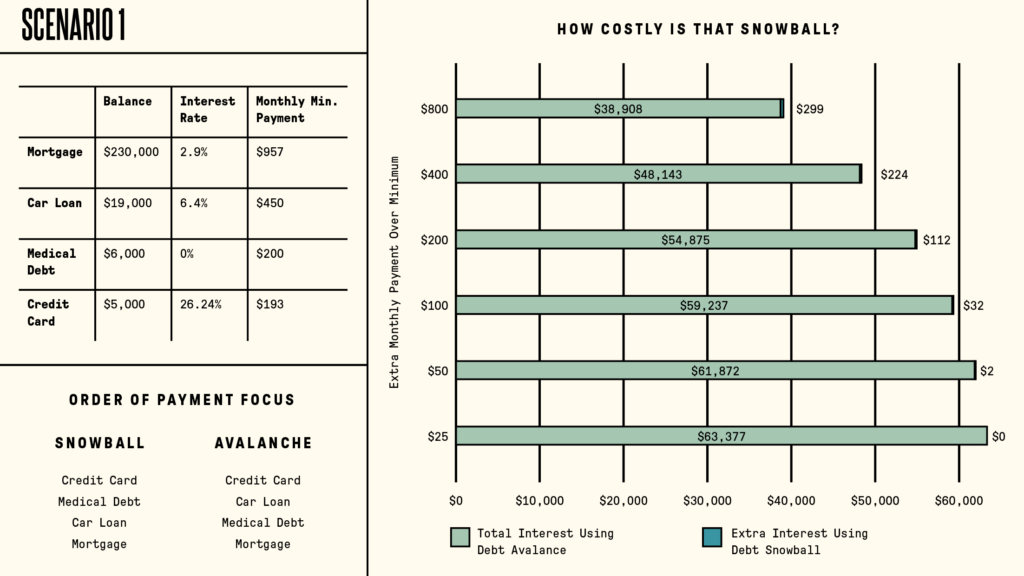

Consider a case study derived from reporting in the Wall Street Journal: “As a Couple Tries to Get Out From Under Debt, a Financial Adviser Weighs In” from November 25, 2022. I’ve rounded and made some assumptions to run the numbers. For example, I assumed that the medical debt holder agreed to be paid interest-free at $200 per month. (Medical debt does not typically accrue interest.) Ramsey’s version of the snowball initially excludes mortgage debt, but both methods pay off mortgages last anyway. I used the calculator at undebt.it to compare the debt snowball and debt avalanche methods, cross-checking some scenarios using Vertex 42’s downloadable spreadsheet. Looking at this scenario, would you choose the debt snowball or debt avalanche?

As it turns out, the debt snowball and debt avalanche differ only slightly.

What about the difference in time to payoff? The debt snowball took an extra month. (Depending on the payment over minimum, total payoff time takes 10-15 years.)

Why the Similarity?

The rough similarity of the two approaches shouldn’t be surprising. They should closely resemble each other because accounts with the smallest balances normally have the highest interest rates. In other words, the debt snowball and debt avalanche often start with the same account and follow a similar path of paying off accounts.

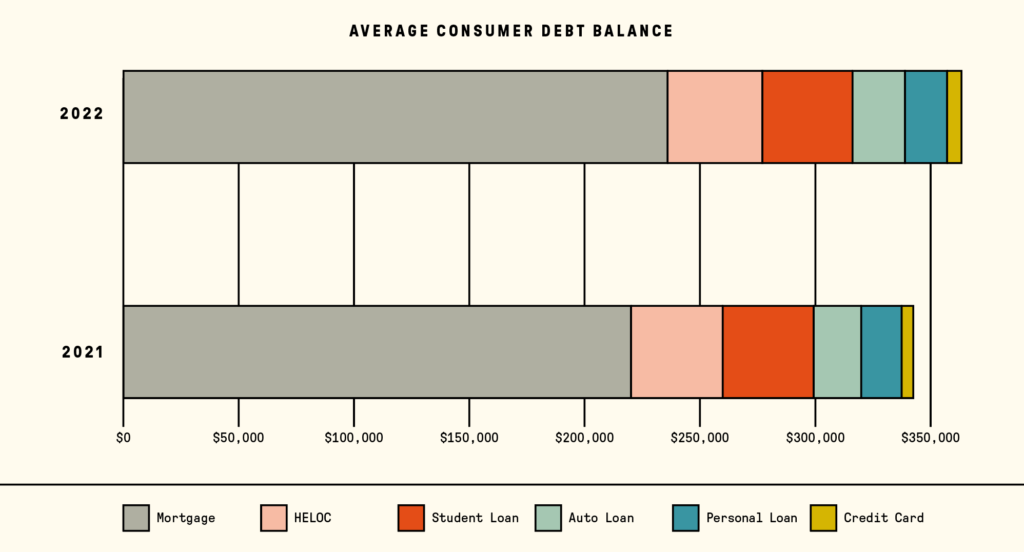

What’s your balance and interest rate on your mortgage? What’s your balance and interest rate on your credit card(s)? Mortgages easily constitute the largest share of the average consumer’s debt balance. Even with rates for new 30-year mortgages around seven percent, they are much cheaper than credit card rates. Notice that the largest average balances tend to correspond to lower interest rates. (Federal student loan rates change once a year, so there is a lag in rate increases.)

That accounts with the smallest balances normally have the highest interest rates makes good sense. Lenders are willing to lend large amounts at relatively low rates when loans are backed by assets (e.g., mortgages, HELOCs, auto loans) or by the government (e.g., many mortgages and student loans). Personal loans and revolving credit are riskier, so lenders extend smaller amounts of credit and charge a higher interest rate. The smaller supply of revolving credit and higher interest rate discourages and prevents massive credit card debt. (It’s easy to owe several hundred thousand dollars on a house; it’s difficult to owe several hundred thousand dollars in credit card debt.)

On the demand side, borrowers borrow more at lower interest rates (holding other relevant factors constant). Why finance a home renovation on a credit card when a HELOC is cheaper? Why finance college education with a more expensive personal loan if a government-backed loan is available?

If the two methods often generate similar results, why do they produce such strong reactions? The economists I talked to responded to the debt snowball with almost universal disdain: The illogic of anyone paying more than necessary irritated them. A person could pay more, but why? In other words, economists tend not to accept the idea that human behavior is more important than the math.

Even though the difference between the strategies is often small, paying more over a longer period does make eliminating debt more difficult. On the other hand, isn’t it at least feasible that a person who sets out to pay off debt gets discouraged and gives up along the way? Might a small win help stay the course?

Difficulties with the Snowball

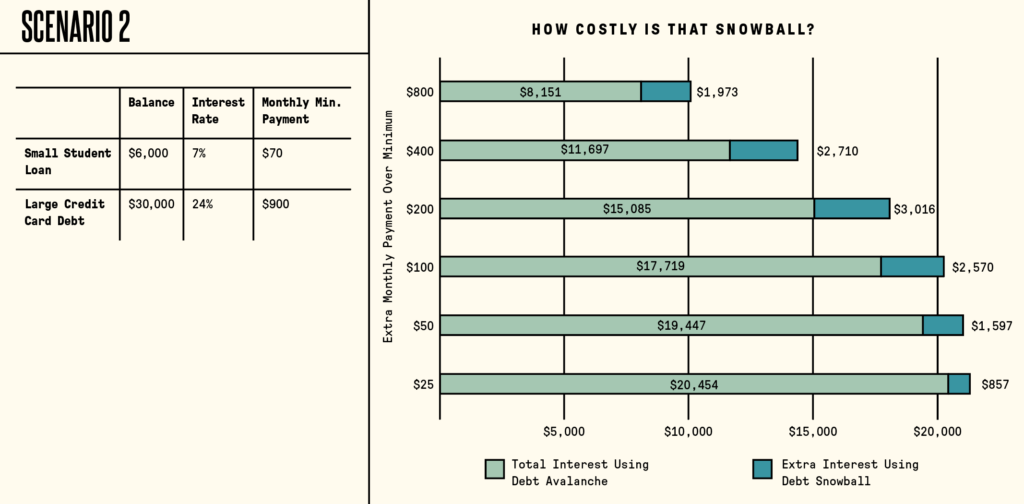

Let’s consider a case where the two methods diverge, such as a small low-interest student loan and a lot of credit card debt. This scenario is a textbook example of the debt snowball. Its recommendation clearly differs from the debt avalanche, allowing a thought experiment: Would small wins motivate you in this case?

Paying $100 over the minimum payment ($1,070 total each month), the debt snowball would tackle the student loan first, eliminating it in 40 months. The debt avalanche would pay off the (much larger) credit card debt first, in 47 months. Would the small win of paying off the first account seven months sooner be motivating enough to pay an extra $2,570 in interest?

That’s exactly Ramsey Solutions’ claim (in a section titled “Why ignore the interest rates?”): “Just because it makes the most sense on paper, doesn’t mean you’ll actually stick to it. … If you begin with the biggest debt, it’ll take a while for you to feel like you’re making any progress. Chances are, you’ll lose steam and give up before you even really get started. And we don’t want that! … Trust us, we’ve helped enough people get out of debt to know the debt snowball is the best (and fastest) way to become debt-free.”

But don’t miss the straw man: “If you begin with the biggest debt, you’ll likely give up.” The debt avalanche does not advocate beginning with the largest debt but the debt with the highest interest rate. As we’ve seen, the largest balances tend to have the lowest interest rates. (Scenario 2 is the exception, not the rule.) So Ramsey Solutions’ argument, in its more accurate but less persuasive form is: Small wins are always more important than interest rate costs, no matter how high the costs.

For the debt snowball to be the best strategy, without exception, the relevant comparison is not the debt snowball versus no strategy but the debt snowball compared to every other possible strategy. But let’s simplify the comparison to the debt snowball versus the debt avalanche. To validate the snowball’s superiority, Ramsey Solutions would need to run a sizable experiment keeping every factor in their system the same (online tools, the envelope method, the support from others seeking to become debt free, the encouragement that becoming debt free is possible, etc.), except using the debt snowball with one group and the debt avalanche with another. I would love to see this data.

Dave Ramsey has helped many people get out of debt. Someone might say, “What’s the big deal? The Ramsey way works.” But is the debt snowball an essential or accidental part of this success? Other motivation factors besides account balances may be more relevant. If the motivation element (rallies, classes, camaraderie, etc.) were combined with the debt avalanche, what would happen then?

The voice of economist Oskar Morgenstern, of the von Neumann–Morgenstern utility theorem, is helpful here. He suggests in The Limits of Economics (published in 1937) that those translating theory into practice have a moral responsibility to incorporate but transcend personal experience, especially for policies that affect many people:

The evaluation of the facts requires a wide experience which can be further extended by special investigations, especially statistical investigations. These are almost invariably necessary since the more far-reaching are the aims of economic policy and accordingly the more comprehensive are the measures, the less adequate is the personal experience of an individual for thoroughly sifting the facts.

Difficulties with the Avalanche

Where Ramsey assumes away the significance of interest-rate costs in eliminating debt, economists tend to assume away the relevance of human behavior. If you ever took Econ 101, you almost certainly heard (but have probably forgotten) the words ceteris paribus: “all else being equal,” a crucial assumption throughout economics. As economists consider an area of investigation, they assume that other relevant factors, whether known or unknown, remain unchanged.

When iPhones fall in price, people want to buy more of them, ceteris paribus. That means the quality of iPhones didn’t change, the quality and price of Samsung phones didn’t change, the price of Apple watches didn’t also change, people’s inflation-adjusted income didn’t also change, Elon Musk didn’t also invent a Neuralink phone, people’s preferences for handheld multipurpose electronics didn’t also change, and so forth. If the only relevant change anywhere was that iPhones got cheaper, then people would want more of them. All else being equal is not a small assumption. (See “Ceteris Paribus Laws” in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.)

The debt avalanche is the smart move ceteris paribus. Embedded in the economic theory is a recognition that other factors may be relevant — we’re just assuming they’re held constant. In other words, the debt avalanche sets the human behavior question aside by holding constant variables like motivation and discipline. Given constant levels of discipline and perseverance, indebted people will pay the smallest amount in interest and pay off debt as quickly as possible by tackling the high interest accounts first. But what happens in the real world when we relax ceteris paribus?

Economists have long recognized the difficulties of ceteris paribus. Some time around the turn of the 20th century, economist and philosopher F. Y. Edgeworth said, “The treating as constant what is variable is the source of most of the fallacies in Political Economy.” Oskar Morgenstern, mentioned earlier, relays that quotation and expands on the idea:

Quite often the necessity of changing one’s views is the result of new and more complete knowledge of the data or of a totally different development of the framework of conditions adopted as “constants” …. There are always forces at work which are masked, mainly by the time factor, and which, immediately they begin to operate, are already shaping the present and the future without yet having given any tangible manifestation. It is not only in the sphere of human psychology that this is true, although that is what naturally comes to mind first. Probably even more important is the circumstance that the time element often seriously falsifies the data that are available on the basis of present knowledge, but nonetheless is continually operating in the direction of revealing at a later date the real forces now at work. Thus at every moment of time there ensues an unmasking of the immediate past. Since, however, human action takes place not in the past but in the present and is directed towards obtaining results in the future which is never fully known, a vast source of error is opened up. At any moment of time economic events, like all events, seem to be proceeding in some particular direction. Only the future, often by bringing things to pass which are contrary to expectation, shows what numerous other possibilities at that time unrealized were present (emphasis added).

In other words, attaining more complete knowledge requires humility — a recognition that knowledge is a work in progress, a willingness to revise what we thought we knew, an appreciation of gaps in our knowledge, an awareness of our need for the clarity that comes only with the passage of time, a sensitivity to the difficulty of translating theory into practice.

A Current Assessment

If successfully eliminating debt depends (or could depend) on human behavior (habits, discipline, and motivation) and math (paying the lowest interest possible would seemingly increase the likelihood of payoff), can we describe the relative importance of each factor? Not yet.

Both Ramsey and interpreters of economic theory can suffer from the same affliction: loudly asserting an assumption as a conclusion. Assuming human behavior trumps all, Ramsey concludes, “Ignore interest rates!” Assuming human behavior isn’t relevant, economists might assert, “Interest rates are all that matter!” But couldn’t eliminating debt be a math problem and a human behavior problem?

In a 2016 article in the Journal of Consumer Research, Keri L. Kettle and co-authors found that small wins do motivate paying off debt. Practically then, the researchers recommend focusing on one account and beginning with the smallest. (See Remi Trudel’s article, “Research: the Best Strategy for Paying off Credit Card Debt,” in Harvard Business Review.) David Gal and Blakeley B. McShane reported similar findings in the Journal of Marketing Research.

But these articles come with a significant caveat. Given the data and experiment designs, these results hold only for accounts with the same interest rate. Motivation matters and surely the math does too, but I haven’t found any research that disentangles the behavioral and mathematical. Whether the debt snowball or debt avalanche is more likely to succeed all the way through debt elimination is an open question.

The upside? In graduate school, after hearing a particularly profound lecture, I asked a professor how he stayed humble. His response: “There’s so much we don’t know.” Recognizing the limits of our knowledge has opposite effects on our learning and our pride. With humble curiosity, we have the opportunity to learn — to close the gap between theory and application — so that we can better marvel at this complex world God has made and better serve the people made in his image.