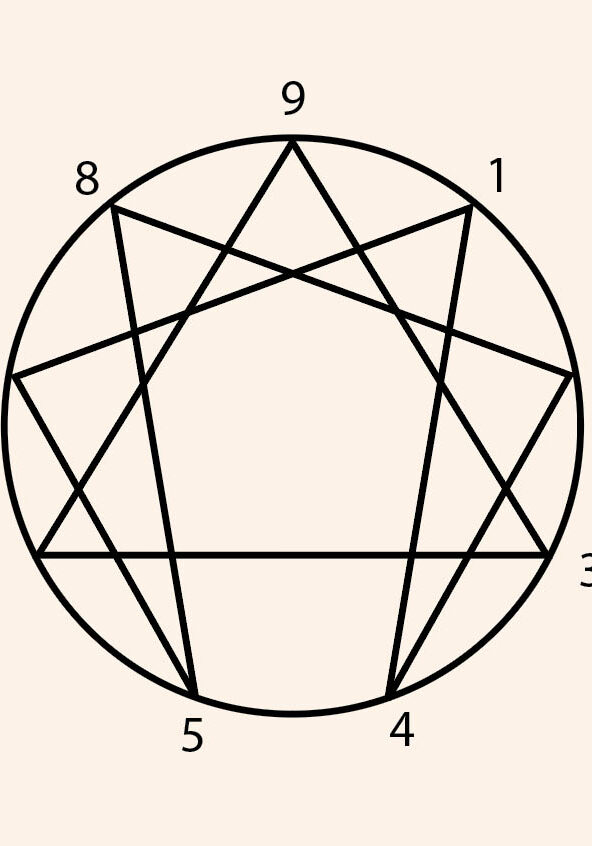

Enneawhatnow?

A micro-guide, for the 17 people who haven’t read about the enneagram yet:

Type 1: the Reformer

The rational, idealistic type: principled, purposeful, self-controlled, and perfectionistic

Type 2: the Helper

The caring, interpersonal type: demonstrative, generous, people-pleasing, and possessive

Type 3: the Achiever

The success-oriented, pragmatic type: adaptive, excelling, driven, and image-conscious

Type 4: the Individualist

The sensitive, withdrawn type: expressive, dramatic, self-absorbed, and temperamental

Type 5: the Investigator

The intense, cerebral type: perceptive, innovative, secretive, and isolated

Type 6: the Loyalist

The committed, security-oriented type: engaging, responsible, anxious, and suspicious

Type 7: the Enthusiast

The busy, fun-loving type: spontaneous, versatile, distractible, and scattered

Type 8: the Challenger

The powerful, dominating type: self-confident, decisive, willful, and confrontational

Type 9: the Peacemaker

The easygoing, self-effacing type: receptive, reassuring, agreeable, and complacent

Spoken words are music, and I love all of it: speeches, poems, monologues, standup comedy. At its best, public speaking is a lure, an enticement; it gives voice to our hopes and dreams. I fell in love with speaking, as many people have throughout history, in my childhood church. And once it got its hooks in me, speaking and preaching never let go. Maybe that’s why I became a public speaker and preacher.

While I love public speaking, most people do not. Listen to the way we talk about public speaking: when someone goes on a long rant about a topic, we say, “She got on her soapbox”; when someone insists on a moral imperative, they are “preaching at us”; a friend of mine was shouted at during a television interview that “we don’t need a history lesson.” Even in churches, where the faithful have long trusted that “faith comes by hearing,” we are seeing an increased resistance to the spoken word.

I fear many speakers don’t realize that most people would sooner do anything else than listen to us talk. The same is true for most teachers, professors, lecturers, and communicators. We forget that public proclamation is a relational act designed to call us into relationship and wholeness. That means speaking is about the hearer, not the speaker.

If speaking is more than the right words or simply the transfer of information, then it makes sense to not only equip ourselves with tools to improve our rhetoric, but also with tools that help us better relationally connect. One of the best tools I’ve found for this is the Enneagram. Why? It teaches us how we see the world, but more than that, it reveals that there are at least nine ways of seeing the world — your way of seeing is just one way of seeing. Knowing this offers us an opportunity to create space for others.

The Enneagram reveals to us the faulty ways we’ve sought to protect ourselves and the flawed ways we’ve attempted to be loved. Knowing this should create humility. Learning that everyone has tried to cover themselves and find love in their own deficient ways should generate compassion. This is how the Enneagram helps cultivate relational connection. It has changed the way my friends, family, and hearers face one another and connect. In knowing ourselves, we discover the depths of other people by coming to appreciate the differences between people, differences that are crucial for a communicator to explore and know.

A communicator best serves hearers by knowing the nine compulsive personality patterns that hearers adopt in order to feel seen, known, and loved. The Enneagram is often reduced to only a personality mapping system, but it is much more than that. In the most basic sense, the Enneagram describes how hearers reach out to the world, in both healthy and unhealthy ways. Knowing one’s motivations, fears, compulsive responses, and paths toward growth are crucial for any individual who wants to be whole. It is also critical for any organization or speaker that wants to aid wholeness and fulfill a mission.

No single way of understanding and seeing the world is preferred, right, or paramount to the others. We are multitudes within ourselves, and we live among multitudes who are also complex, which means we must be more intentional about how we communicate, knowing that our way is not the only way even as we hold the microphone.

Sometimes our hearers don’t connect with what we’re saying because it is based on how we see the world rather than how they see the world. And we mistakenly think we see the world as it is. As has been quoted by many, “We don’t see the world as it is, we see it as we are.” For years, I’ve signaled to thousands of people — in churches, at conferences, conventions, retreats, and other gatherings — that my reflexive and compulsive ways of seeing and being in the world are the ways to see and be in the world. I did not know I had a myopic perspective—and most other speakers don’t realize it either—yet we do.

This raises a question. What about people who don’t interpret the world the way I do, who don’t hear what I hear, who don’t see with my lens? Or yours? I’m not merely talking about differing worldviews or competing philosophies, all of which are choppy enough seas to navigate. But what should we do when what foundationally motivates us and the way we process reality are genuinely good yet wildly dissimilar?

It’s entirely possible that communicators inadvertently disengage a good portion of their hearers by overlooking the reality that their thought patterns and words are rooted in a particular way of seeing and being in the world. Preparing public proclamations under the assumption that people hear, interpret, and understand the same way we as speakers do, might be the reason some folks drift into sleepiness during our talks and presentations.

What if the reason that you didn’t close that last deal, convince that executive board, or get a yes to your invitation was an understandable naiveté about the difference between the way you see the world and the way your hearer sees the world? What if you were talking only to yourself?

As a communicator, the way you see the world is valuable; yet if that is the only way you speak of the world, your talk will be cheap.