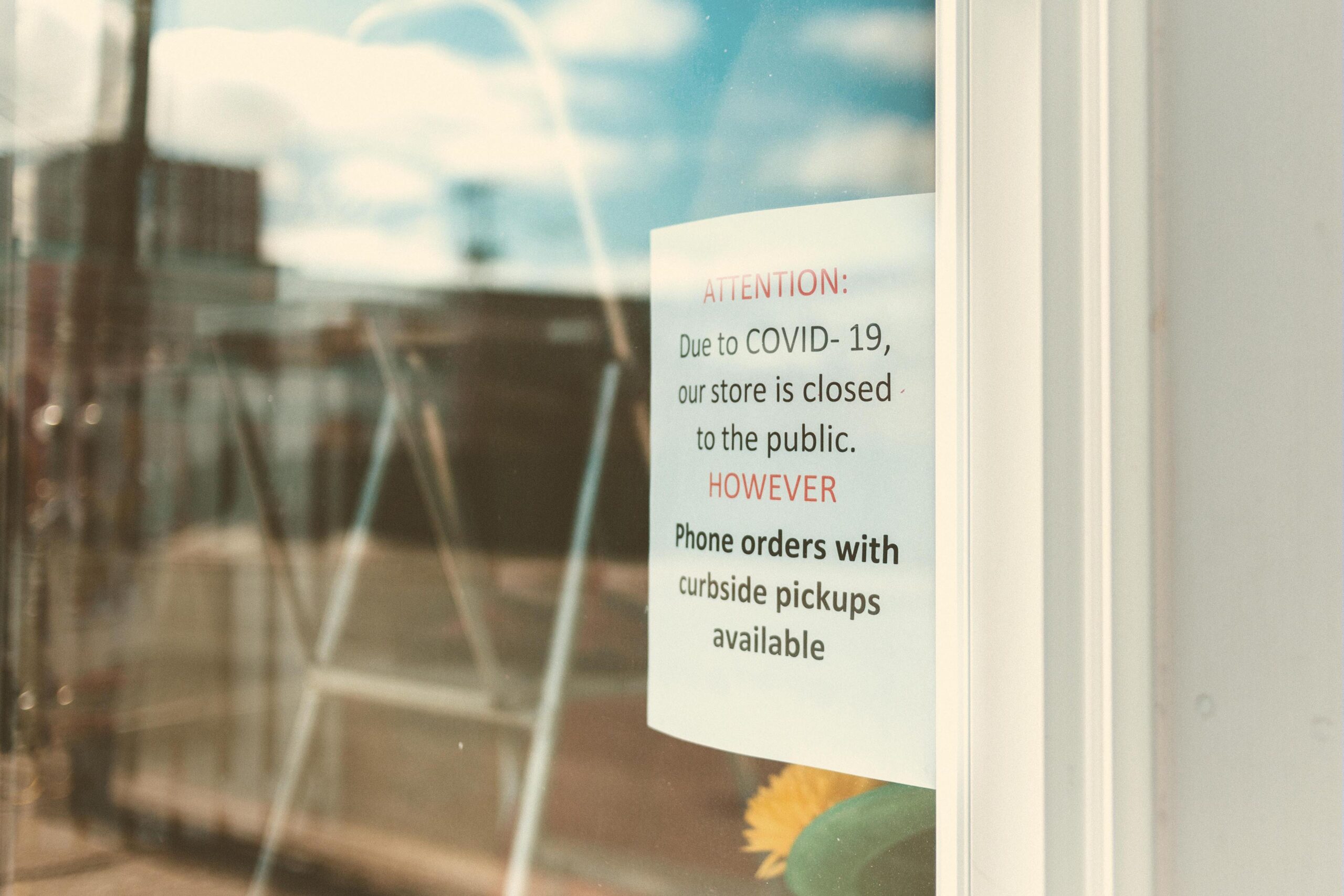

We don’t need to tell you how much the coronavirus upended, well, almost everything. And probably nowhere did that look as dramatic than in the economy. Some businesses spiked, with needs for their work skyrocketing. Many companies couldn’t make it. In fact, through the summer of 2020, more than 80,000 local businesses permanently closed, according to data from Yelp, Inc. But whether it’s been feast or famine, nearly every company has needed to adjust, to pivot. To do things differently because of COVID-19.

Throughout the summer, Common Good editors talked with companies around the country in order to gather some of the most interesting and inspiring stories out there. You’re welcome.

01 SNAPBAR

These Boxes Support Local Spots and Come from … a Photobooth Company

A photobooth company, in case you’re wondering, is functionally an event company that supplies, well, photobooths. Sam Eitzen started Snapbar with his brother in 2012 as a sort of side-hustle.

“We landed on the Inc. 500 list at number 473 in 2019,” Eitzen said during a phone call in August, “because we’d grown at about 1,000 percent between 2015 and 2018. Then 2019 was an even better year, and 2020 was looking to be better still.”

The Seattle-based Snapbar did just over $3 million in revenue in 2019, and the company projected between $4 million and $5 million in 2020. But by March, enough major events had been canceled to sound the Snapbar alarms.

On March 11, Eitzen couldn’t sleep. So he got out of bed and came up with 50 ideas, ideas to save the company, to save his staff. After workshopping the ideas with the Snapbar leadership team and his brother, they settled on gift boxes.

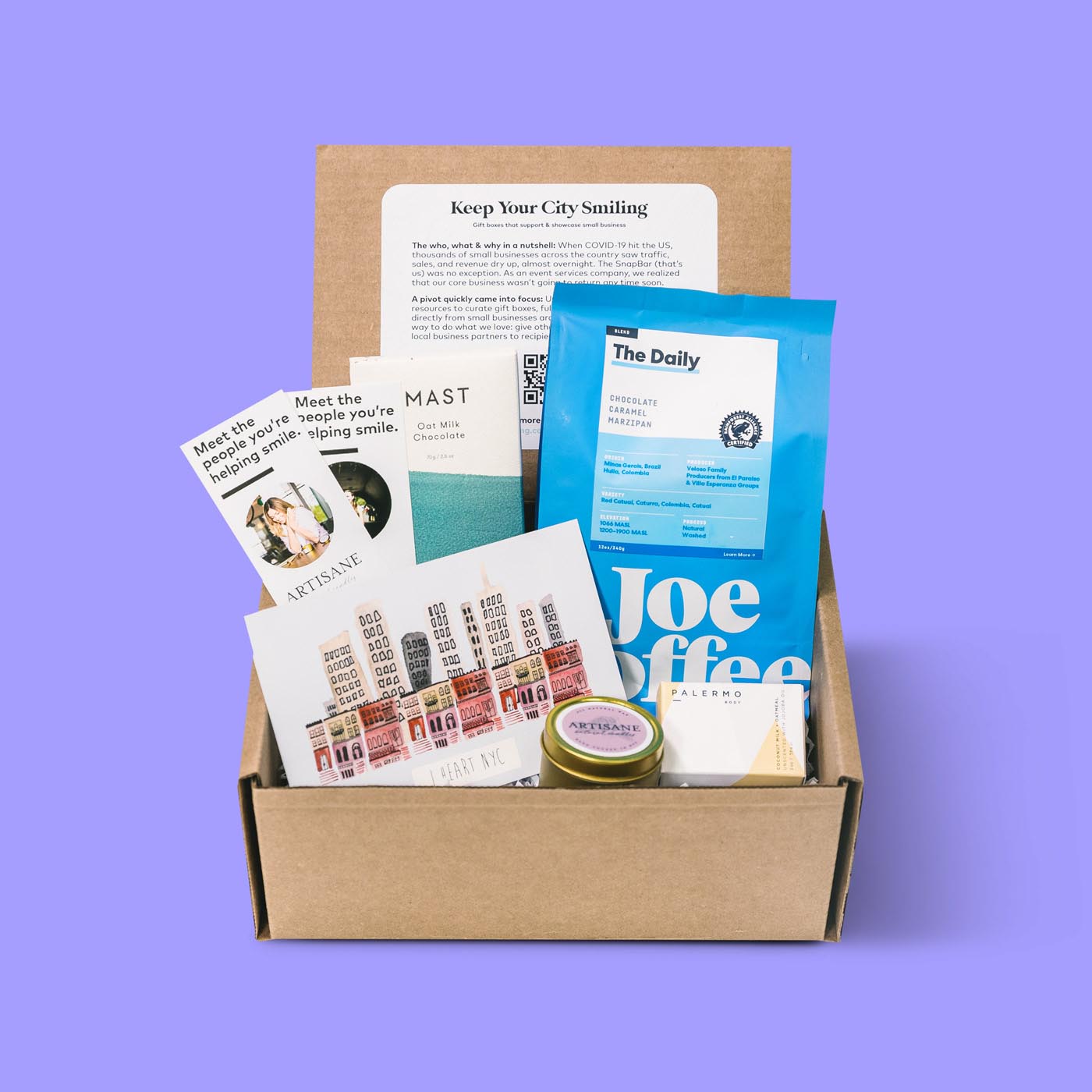

“We decided that we would create gift boxes and care packages that support small business and local vendors,” says Eitzen. “That was key, because March was the height of everything being shut down, and small businesses” — Seattle and San Francisco were of particular concern — “were doomed if they didn’t have an online presence.”

The Eitzen brothers told their team the idea on March 16 and launched a website on March 19. That’s right, what’s now Keep Your City Smiling was born in eight days.

Initially, Keep Your City Smiling was an e-commerce company, selling individual boxes straight to consumers. They sold 8,000 boxes worth $525,000 in the first three months, enough income to keep them in business. About three months in, Eitzen and Co., in search of more sustainability, evolved the model toward corporate gifting, where the team connects “global organizations to local vendors.”

Eitzen goes on: “We want to encourage our clients to think about gifting with intention and telling these stories of local founders versus just looking at it from a dollar perspective and always going for the products that are mass-produced anonymously somewhere in the world.”

And all while Keep Your City Smiling kept 15 of 18 Snapbar team members employed and sustained hundreds of small businesses in the Pacific Northwest, Snapbar’s director of engineering worked, as Eitzen describes, “day and night building a software product that we had gotten an idea for in March that we now call Virtual Booth.” And that product has returned a good chunk of Snapbar’s core business and positioned the Eitzens to spin out a whole new company. And to keep smiling.

02 CREA AND CROSSROADS CHURCH

A Church Held a 24-Hour Mask-Making Vigil on Easter

When Travis Lowe’s church couldn’t gather on Easter because of COVID-19 restrictions, the congregation got creative with how to gather — separately — to serve their community.

Crossroads Church in Bluefield, West Virginia, where Lowe pastors, is a congregation of about 150 people. Within an hour of announcing the family group-style service project, 25 families volunteered to spend one hour each making masks and face shields for local hospitals, home health agencies, dentist offices. They used a makerspace, Crea, to host the families who spent the hour cutting, sewing, marking patterns, assembling face shields on that Easter Sunday.

“The people in my church saw this opportunity as a chance to not just go to church, but to be the church,” Lowe said in an email exchange. “Easter is about life and we saw our efforts as a visible demonstration of the life that we preach. Everyone quickly saw this as more than a service project but as a way to celebrate the resurrection of Jesus.”

Lowe thinks his church did this not only as a way to gather, but because they believed it was a way to “be the church.” The Crossroads congregation used this opportunity to serve Bluefield despite restrictions and with the resources in front of them.

03 SAMUELS ENGINEERING

Go Go Go Joseph? One Engineering Firm Retained Nearly 100% of Employees

They’ve spent 20 years getting ready for this. Claudia and Evrod Samuels have spent the last 20 years operating an engineering firm in Denver, Colorado. Samuels Engineering is a 175-person company that partners with clients in cities around the United States and in various countries around the world. Samuels Engineering works in a variety of sectors, including engineering and construction management for heavy industrial projects.

From the beginning of their business venture, the Samuels have believed their employees are the most valuable asset to the company. So, when an economic or industry downturn occurs (every few years), employees are the last, instead of the first, thing to go.

This philosophy of retaining workers is built on principles the Samuels find in the Bible, from stories like Joseph and Gideon. In Genesis 37-41, Joseph prepares his people, land, and even strangers for a famine by saving resources to provide. The Samuels do the same. They’ve been preparing for something just like COVID-19.

Two programs the Samuels implemented kept their employees afloat during pandemic-related shutdowns: EPI (employee preservation initiative) and MIA (minimum income assurance). The minimum income assurance guarantees a particular income each month for employees not based on hours worked; the employee preservation initiative is something they have used since the ’08 crisis, and it includes a reduction of discretionary spending, hours employees work, and programs to save money. Their Joseph-style planning has allowed them never to cut health care.

And, more than making a profit, they believe their work is caring for their employees like a family, which is something worth getting ready for.

04 TULBELT

Download This: A Better List Than Angie’s

When pastor Jan Vezikov’s dad passed out at work earlier this year, doctors determined nothing was wrong with him. Except stress. Vezikov’s father has owned his own painting company for 30 years and has recently struggled to find enough help. And due to the weather and pandemic restrictions this May, exterior painting jobs were slow or nonexistent. His crew either didn’t have work, or quit.

This inspired Vezikov, who works as a church planter in Boston, to think how he could help contract workers in his community. Contract workers usually have gaps in their schedules. Filling those gaps with reputable jobs, bid on through an app, is what generated the idea for Tulbelt.

It’s like Angie’s List, the ubiquitous online contractor-finding service, but with some major differences. First, it’s free and app-based. Second, it features a mutual rating system that allows workers and clients each to rate their experience. Frankly, Tulbelt is better for contractors.

Vezikov and his team, mostly pastors from his church, Mosaic Church Boston, believe this creates both accountability and sustainable income for workers. It also crosses barrier lines that aren’t usually crossed in certain neighborhoods, providing work for people in new ways.

Tulbelt launched in the midst of COVID-19 and has seen exponential growth, with 6,500 active users as of September, and more than 2,000 active projects in 39 states.

“We see God’s hand in that it was created for such a moment as this,” he said. “So it’s helped people, actually, who are hurt by the pandemic financially to find work, and people who weren’t hurt by the pandemic financially, white-collar workers, could provide the work so the framework uses people who work with their fingertips to provide work for people who work with their hands. Everybody wins because we’re in the win-win business.”