Oh our hearts are

Full of empty rooms and hallways

In our chests

Like innkeepers

We got many rules and always

Charge a guest

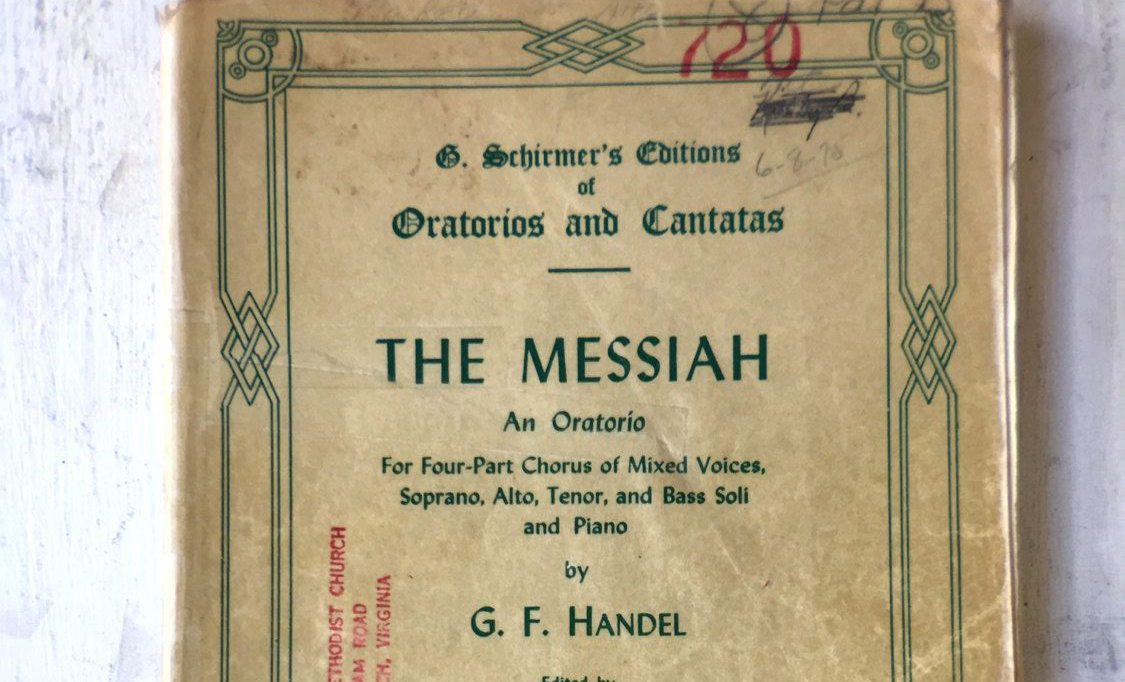

With these words to close her stunning Christmas album Immanuel, singer-songwriter Melanie Penn likens our hearts to the inns and innkeepers of first-century Bethlehem. She invites us to consider our responses to the Gift of Love, should it ask to come in:

But if love knocks on the door at night

On a journey

And wants to come inside

Do we let it in?

Do we invite love to come near?

The arrival of Joseph and Mary was not the first time that Bethlehem faced the question of how it would receive love incarnate.

A millennium before, in the age when Israel had no king, there was a famine in the land. A man named Elimelech left Bethlehem with his wife, Naomi, and their two sons. They settled in the fields of Moab, where their sons found wives — Orpah and Ruth. Soon, an even more tragic famine befell Naomi. Her husband died, followed by her sons 10 years later.

Bereaved of her husband and two sons, having only two daughters-in-law, Naomi decided to return to Bethlehem, having heard the famine had ended. Her Moabite daughters-in-law meant to go with her. But Naomi encouraged them to return to their families and their gods, warning that her life was too bitter for them to share. The Lord was, she insisted, set against her. Orpah kissed Naomi, leaving her home. Ruth refused to leave, saying:

Don’t plead with me to abandon you

or to return and not follow you.

For wherever you go, I will go,

and wherever you live, I will live;

your people will be my people,

and your God will be my God.

Where you die, I will die,

and there I will be buried.

May the Lord punish me,

and do so severely,

if anything but death separates you and me. (Ruth 1:16–17)

Ruth’s vow is a remarkable expression of love — hesed, to be exact. This hesed, frequently translated as “steadfast love” or “faithful love,” is at the heart of who God is. “The Lord is a compassionate and gracious God, slow to anger and abounding in faithful love and truth” (Ex 34:6–7). This love is covenant faithfulness — the Lord is absolutely committed to keeping his covenant promises to his people. In response, the Lord calls his people to live lives characterized by hesed. They are to love him with all their heart, soul, and mind. Likewise, they are to love their neighbor as themselves. According to Jesus, “All the Law and the Prophets depend on these two commands” (Matt 22:40).

So Ruth’s words to her mother-in-law demonstrate that she is a woman marked by faithful love for her neighbor. The marriage covenant that united Ruth and Orpah with their respective husbands came with covenant responsibilities to their new family. When their father-in-law and then husbands died, the obligation to care for Naomi fell to them. Orpah forsook the covenant. Ruth kept the covenant, pledging her life to the Lord and to Naomi.

Consider the cost: She was a Moabite, whom the Israelites were to have nothing to do with. She was, evidently, barren after ten years of marriage (Ruth 1:21). Without the protection of a father or husband, and with no apparent prospect for a son, Ruth pledged to live out her days, in a place hostile to her, loving her mother-in-law, who had lost love. Vulnerable to abuse, she made the journey to live out faithful love.

Ruth traveled to Bethlehem as hesed in the flesh. How would Bethlehem receive her? Would she be an outcast? Would she be abused, raped, rejected? Or would room be made for her here?

Arriving in Bethlehem at the start of the barley harvest, Ruth went into the fields to glean fallen grain for Naomi and herself, and in God’s providence, the Moabitess found herself in the field of Boaz. Boaz inquired about Ruth and learned about her costly and courageous faithfulness to Naomi, and he found love standing in his field, but outside his circle. Boaz responded to Ruth’s story, “There is room for you here.” He insisted that Ruth would remain in his fields with his female servants, be protected by his men, drink from his water jars, join the circle of his people, and eat his food.

Boaz, like Ruth, was a living, breathing picture of the Lord’s covenant love. Eventually, they would marry. Their son Obed would father Jesse, the father of David — to whom was promised a descendant, the king who would reign forever.

In Bethlehem, 1,100 years later, Jesus the Son of David traveled in utero to the home of his distant great-grandparents, Boaz and Ruth. Conceived by the Holy Spirit, this child was, indeed, hesed in the flesh. He was the true and greater Ruth, the true and better Boaz.

Bethlehem faced the question again: When Love incarnate knocked, how would the city respond? When Ruth entered the town, a forbidden person, she was welcomed by a heart opened wide (Deut 23:3). When Mary gave birth, “she wrapped him tightly in cloth and laid him in a manger, because there was no guest room available for them” (Luke 2:7). Mary came pregnant with the Son of God, yet they were turned away to sleep with the animals.

A manger was not a bed fit for the Messiah — but it was an entry fit for his mission. Jesus was sent by the love of God (John 3:16). He came to be the love his people failed to embody. When we see Jesus — humbled in life, cursed in death, and triumphant in resurrection — we see love. “Love consists in this: not that we loved God, but that he loved us and sent his Son to be the atoning sacrifice for our sins” (1 John 4:10).

As with the Old Covenant, so it is with the New: God’s love calls us to walk in love, for God and our neighbor. As 1 John 4:11 says, “If God loved us in this way, we also must love one another.” But too often, we find ourselves reluctant to love. Love seems dormant in our hearts. How do we awaken love? Here too, Ruth and Boaz offer a lesson.

When Ruth asked Boaz why she found favor with him despite being a foreigner, he replied, “May the Lord reward you for what you have done, and may you receive a full reward from the Lord God of Israel, under whose wings you have come for refuge” (Ruth 2:11–12). Ruth sought refuge under the wings of the Lord — that is, she received the love of the Lord. Ruth’s reception of her late husband’s religion went beyond external adaptation for her in-laws.

And what of Boaz? Where did he learn such kindness? I believe he learned it from his father and mother. The end of Ruth tells us that Boaz was the son of Salmon and Rahab — the same Rahab who offered a hiding place to the Israelite spies in Jericho on the condition that the Lord show kindness to her and her family (Josh 2). She was a Canaanite — a people the Israelites were forbidden to marry, but Salmon recognized Rahab as a Canaanite by birth but an Israelite by faith (Deut 7:1–4). Like Ruth, she had taken refuge under the wings of the Lord. And so, like Boaz to Ruth, Salmon offered Rahab refuge. Ruth and Boaz remind us that “we love because he first loved us” (1 John 4:19).

Penn’s Immanuel ends with this:

Weary traveler

With a child to be born soon

They saw a light inside

What do we do?

Do we turn away

Or open our hearts wide?

There is room for you here.

In many traditions, the second Advent candle — the Bethlehem Candle — represents love. As you remember the birth of Christ in Bethlehem this second week of Advent, and when your neighbor knocks in need of kindness, will you make room?