In downtown Eau Claire, Wisconsin, BreakThru Rage Rooms is now open for business. These rage or smash rooms are springing up everywhere, catering to those wanting release from a wide array of hurts such as marriage woes, kid problems, neighborhood feuds, and workplace anger.

According to BreakThru’s owner, J.P. Parker, “It’s a space where you can get rid of your anger and stress by breaking things in a safe manner. … Before getting down to business, you put on protective coveralls, a face shield, and gloves. Depending on the package you purchase, you then get to destroy a range of items, including dishes, glass panes, small appliances, and larger items like televisions and desks.”

Even corporate America is getting involved by encouraging employees to bring all of their emotions to work, Fortune Magazine reported. During its Wellness Week, Salem Health, for example, invited hospital employees “to write whatever grievances and difficult emotions they had on plates, and then smash them against the wall.”

Though smash rooms might bring immediate relief, are they healthy in the long term? Liz Fossilien and Mollie West Duffy, in “How to Manage Your Anger at Work,” warn that “Blowing off steam is not as productive as you might think.”

In the case of rage rooms, they write, breaking things actually escalates rather than dissipates anger. Ironically, even Ramsey Solutions (Dave Ramsey’s global financial outfit), offers caution about workplace anger: “Dealing with your rage through aggression simply reinforces the rage. Channeling anger and frustration in quick, violent bursts can make this expression your default reaction.”

How should we be responding to anger?

Anger is caused by and expressed in many different ways, but most anger is unholy, falling far short of the righteous anger we see voiced by God the Father and Jesus throughout Scripture (See: Exod 32:10–11; Num 11:1–2; Deut 9:8; 2 Kings 13:3; Lam 2:2; Ezek 7:8; Matt 21:12–13; Mark 3:5, 10:14, 11:15–17; John 2:13–16). Teacher and activist, Parker Palmer, in A Hidden Wholeness, describes violence holistically as any behavior “violating the identity and integrity of another person.” By this definition, most anger in the world today inflicts lasting and identity-diminishing harm.

Mark Roberts, senior strategist for Fuller Theological Seminary’s Max De Pree Center for Leadership, recently published a helpful six-part devotional on anger. His reflections are grounded in Paul’s admonition to the church of Ephesus:

So then, putting away falsehood, let each of you speak the truth with your neighbor, for we are members of one another. Be angry but do not sin; do not let the sun go down on your anger, and do not make room for the devil. (Eph 4:25–27)

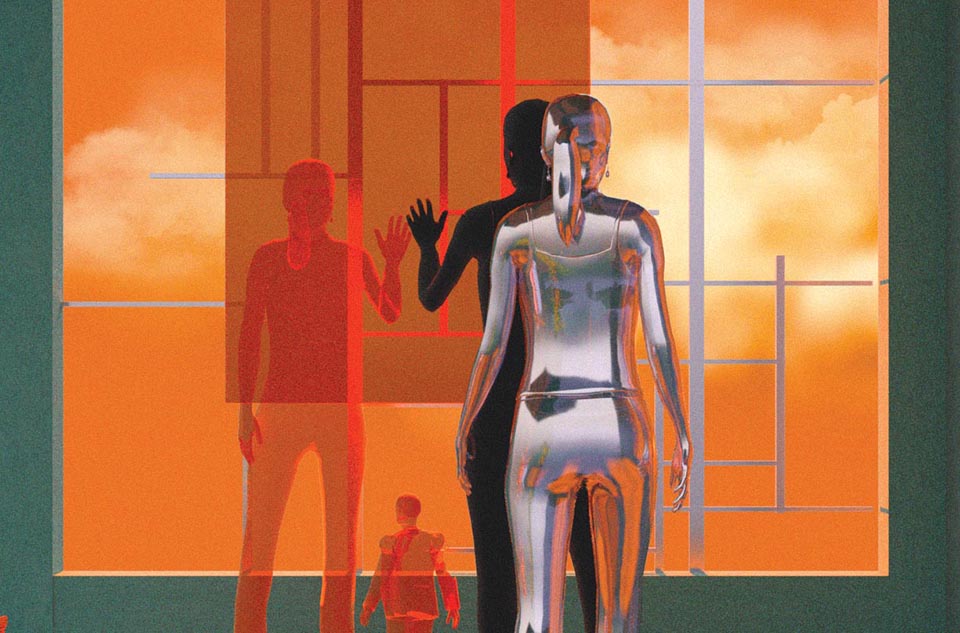

What does it mean to be angry but not sin? Of all the questions our communities face, this may be one of the most important. Imagine the healing that would occur if we could transform physical, emotional, and identity-degrading anger into something constructive rather than destructive.

In his exposition, Roberts examines what Paul means by not letting the sun go down on our anger. A literal injunction, he teaches, is not what’s intended; we often need time to settle our emotions and discern the best way to express what we’re feeling. Even so, anger should not be given time to putrefy. It should “not be stored up,” or “hoarded.”

So how are we to deal constructively with frustration, even fury? We’re not to deny it or express it without any precautionary guardrails. Nor are we to scream at others or smash things. Rather, we’re to honestly acknowledge it. Prayer is one effective pathway to begin to transform anger (consider the Psalms), as is speaking to a wise friend or counselor. Ephesians 4:25 is highly instructive here, reminding us that we’re bound to one another in discerning the truth. A wise counselor provides perspective for channeling our anger toward profitable ends. When we seek wisdom for our anger through the counsel of our neighbors, we eliminate “room for the devil,” as Ephesians 4:27 informs.

Practicing nonviolent resistance

The finest American model for dealing constructively with anger may be Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who at a critical moment in his life reflected:

While I lay in that quiet front bedroom, with a distant street lamp throwing a reassuring glow through the curtained window, I began to think of the viciousness of people who would bomb my home. I could feel the anger rising when I realized that my wife and baby could have been killed. I thought about the city commissioners and all the statements they had made about me and the Negro generally. I was once more on the verge of corroding hatred. And once more I caught myself and said: You must not allow yourself to become bitter.

Learning from Henry David Thoreau, Mahatma Gandhi, Howard Thurman, and others who had gone before him, King orchestrated his entire civil rights campaign on this principle of nonviolent resistance. Grounded in his deep commitment to Scripture and the life of Jesus, he realized that peaceful resistance “had a way of disarming the opponent” by revealing their “moral defenses” and working on their consciences. Peaceful resistance also offered a redemptive pathway for Black Americans “to secure moral ends through moral means,” King notes in The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. Accordingly, he says, nonviolence is the “weapon that cuts without wounding” and “ennobles the man who wields it.”

King, his life and legacy, offers fresh perspectives for our anger-infused communities. Nonviolent resistance can be carried out collectively against systemic injustice, but it can also be exercised moment by moment against wrongs we experience personally. As King explains:

The way of acquiescence leads to moral and spiritual suicide. The way of violence leads to bitterness in the survivors and brutality in the destroyers. But the way of nonviolence leads to redemption and the creation of the beloved community.

Palmer punctuates this point. Nonviolent resistance, he writes, gives us an option other than a typical fight or flight response, “a commitment to act in every situation in ways that honor the soul.”

Practical strategies for peaceful resistance at work

Most of us spend many of our hours at work, where we face a myriad of small and big challenges. When it comes to better managing our anger, there may be no greater practice venue than our workplaces. Below are three immediate strategies you might engage to channel your frustrations more constructively.

- Pay attention to microstress at work, moments of brief anxiety, setbacks, and pressures that permeate your workday. As chronicled in Harvard Business Review, “microstressors may be hard to spot individually, but cumulatively they pack an enormous punch.” The unrelenting demands of technology can be one such instigator, especially as they interrupt our deeper workflows. Some of the sources of our frustrations, worries, and anger — such as the constant bombardment of technological intrusion — can be eliminated. As we gain mastery at work to eliminate microstress, we claim agency in other parts of our life.

- Seek wisdom for reducing the stress and frustration we cause others. Authors Rob Cross and Karen Dillon in their forthcoming book, The Microstress Effect, offer sage advice: “When we create microstress for others, it inevitably boomerangs in one form or another … emitting less [stress] means we’ll receive less in return.” Most of us know first hand that negative relational experiences take a heavy emotional toll. As we find ways to transform our anger, to not emit it unhealthily onto others, we create a cycle of virtue.

- Leverage workplace experiences to probe what’s behind our feelings of anger. This is challenging to do in real time, but try it for a week and see what you learn. Fossilien and Duffy recommend the following questions:

What triggered your anger or frustration and what feelings are underneath it?

What longer-term outcomes are desirable and what steps might you take to work toward these results?

What risks and gains do you need to consider?

Although most of us are not facing the perils confronted by King, when we have the courage to look closely into our anger, we develop a greater mastery in dealing with it constructively. When King was imprisoned, he wrote letters and engaged in long-term strategic planning. When he faced the fury of fire hoses and police brutality, he planned peaceful boycotts and marches. When he met the betrayal of friends, he turned to God in prayer and found comfort in the body of Christ.

King demonstrated what it can look like to transform our anger into something redemptive that, in both small and big ways, stops the contagion of hate and even leads to forgiveness, a place where love and faithfulness meet. As the Psalmist reminds us: “Steadfast love and faithfulness will meet; righteousness and peace will kiss each other” (Ps 85:10).