After months of pleading from analysts and motioning by central bankers, the Federal Reserve has raised interest rates. The Fed raises the so-called federal funds rate in fractions of a percent. The current rate sits between 0.25 percent and 0.5 percent, or 25 to 50 basis points (bps) — a number that sat at nearly zero since the pandemic hit two years ago. This means borrowing money costs a little more now, and the Fed intends to raise rates up to seven more times over the next two years. This pushes interest rates up on many other loans, such as mortgages, for which the current average rate is now over four percent. And as interest rates rise, employment may fall, and we may enter into a recession.

I don’t say this to scare you. It happens — and it also might not happen.

A recent article in The Wall Street Journal summarized a lot of what’s been going on and what it might mean. Here’s what Nick Timiraos, chief economics correspondent, said:

“The Fed’s ideal scenario is that inflation expectations stay anchored and price pressures diminish, allowing it to slow the pace of rate increase and thus avoid a recession — a so-called soft landing.” But one investor argued that “at this point, I’m not sure anyone believes they’ll land the plane on the strip … Without a little bit of luck that will be a tight landing spot.”

This isn’t the end of the world. The definition of a recession is that GDP growth slows for two consecutive quarters. That’s it.

Two questions may come to mind: Why do people think we may enter a recession, and what might that mean for the average person? To more clearly answer these questions, ahead I’ll discuss some economic theory as well as one of the largest capital markets — the bond market.

Why do experts think we may enter a recession?

For the first question, the answer lies in two ideas — one theoretical and one practical.

Essentially, interest rates are the price to borrow money. I’ve written here before that higher interest rates will slow borrowing. When they’re higher, people tend to borrow less money. Less borrowing and buying means less production, which means fewer people are needed for production, which means there are fewer jobs to be filled. Fewer jobs mean less income for people, which means less spending — and the overall economy slows down.

This theory behind why a recession would happen has been covered in recent Quick Notes installments; if you need a refresher, that’s here and here. To see how and why this happens and what the Fed does about it, you can also watch this five-minute video from The Wall Street Journal.

Back to the recession. The other, more practical reason why people think we may enter into a recession has something to do with investor expectations.

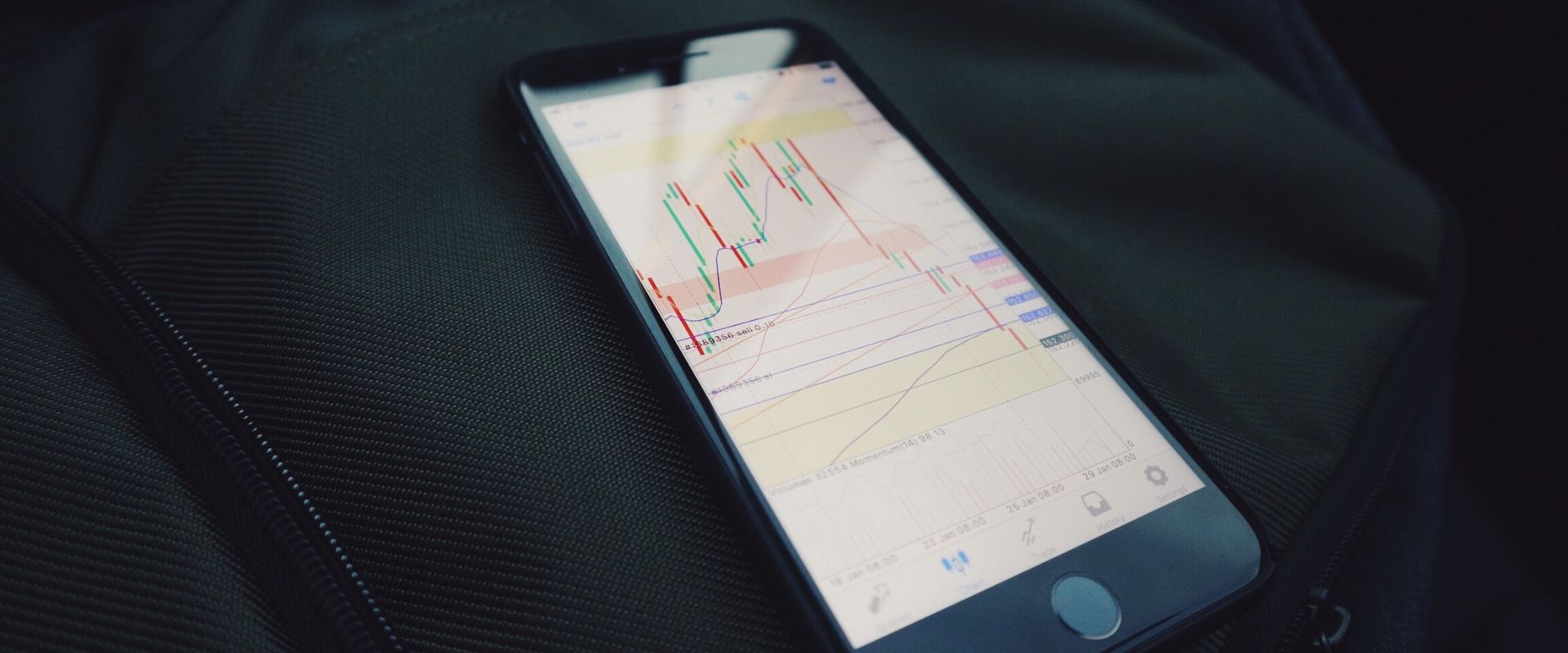

For most people, when they think of “the market,” they think of the stock market. But there are lots of other markets out there, including markets for commodities and bonds. All of the markets in which people trade things are called capital markets. And the bond market is where investors trade debts instead of shares of stock, and it’s actually twice the size of the stock market.

One of the types of bonds that investors trade are notes from the U.S. Treasury. These come in one-month notes and can range all the way up to 30-year notes. This means that you can invest your money in a note and receive the money back when it “matures,” which can be in a month or in 30 years, all while accruing interest payments along the way. In brief, when the yield on a bond (its expected return) goes up, that means there are fewer people trading that bond, so the price goes down because few people want it. Lower demand lowers the price, but a lower price raises the yield to get investor interest.

For you financial nerds out there, consider this explanation from a recent Bloomberg article on the bond market.

Looking at this type of bond is significant because of what happened last week when the Fed announced they were raising interest rates: The yields on five- and 10-year bonds inverted. In other words, the five-year bonds had higher yields than the 10-year bonds. That’s because investors “have lost confidence in the economy’s outlook,” as noted by an explainer from Reuters. Every time this has happened since 1955, except once, a recession has followed within six to 24 months.

What might that mean for the average person?

Technical terms aside, the average person in America may not be affected in any major way, though it will become more expensive to borrow money for large purchases. The stock market will become more volatile than it already is, and inflation will stick around for the foreseeable future.

Recessions, however, tend to last less than a year, sometimes up to 18 months. During that span, prices could come down, the stock market could come down to normal levels, and if so, the economy will pick back up again. It’s possible that some Americans may lose their jobs, but as that’s partly dependent on the severity and longevity of a recession, we can hope that won’t be many. Of course, keep in mind that no one can predict the future — and history isn’t always the best guide for what will happen in the future — and I’m only offering an opinion (not investment advice).

To prepare, many financial advisors recommend saving three to six months’ expenses in an emergency fund. That may seem daunting given some incomes, debt burdens, or tithing commitments. Yet starting with just a few hundred dollars can go a long way in protecting yourself ahead of hard times. Financial wellness experts say a little savings also helps reduce stress and anxiety for this reason.

Given all the economic hoopla and conflict around the world, it will never hurt to think about the kind of future you want to have and protect it before the clouds darken.