During the last few weeks, policymakers at the Federal Reserve — our nation’s central bank — have moved toward slowing down the economy by raising interest rates. The Fed chair, Jerome H. Powell, suggested earlier this week that rates will likely go up in March. Months, even years, of stimulus payments have pushed money into the system, leading to rising inflation. Others believe inflation is also bubbling up because of supply chain disruptions and workers calling out sick. It’s probably a bit of both.

How will these rising interest rates affect the economy?

Interest is simply the price to borrow money. Low rates allow borrowers — from individuals to businesses to governments — to borrow money at a lower cost. This increases the amount of money in our financial system. More money creates more demand, which raises prices.

Think about all those stimulus payments. And think about all the savings many Americans accumulated at the beginning of the pandemic while they couldn’t go to the movies or restaurants or airports. If people have more money, they’re more willing to pay higher prices for the things they want. Philosophers developed what’s called the “quantity theory of money” in the 16th and 17th centuries to explain this phenomenon.

Thus, in order to slow down the economy, or to remove money from the system, the Fed needs to lower prices. And to do so, it raises interest rates. In theory, using sophisticated macroeconomic models like this one, policymakers think this should lower inflation.

So why does this matter now, and what does the current inflation data say?

The latest Consumer Price Index (CPI) data puts inflation at over 7 percent, while the Fed’s preferred number, the so-called core inflation rate, which excludes volatile prices for food and energy, hovers at 5.5 percent. Used car prices have risen 37 percent and furniture 14 percent, while the median house price has increased over 19 percent.

Inflation is like a hidden tax. Prices for everything from steaks to clothes to dollar store products have increased, which lowers the purchasing power of your money. Unstable prices create a lot of problems aside from purchasing power, like distorted wages and financial models that lead to major disruptions in an economy.

The Fed aims for stable inflation around 2 percent, less than half its current rate. Policymakers have several tools in their toolbelt to get back to that point. They essentially have to take money out of our financial system. To do so, they can sell bonds on the open market, which reduces the interest rate. And they can increase the reserve requirement for banks, which is basically a bank’s savings account.

This simple animated video called “How the economic machine works” helps explain some of this.

In it, Ray Dalio, the leader of the world’s largest hedge fund, describes how the economy is like a simple machine. A person sells something, a person buys something, and the sum of all these transactions makes up the economy. But most people pay for things with credit, not cash. That is, they use loans and credit cards to buy what they want, from groceries to houses. Credit allows us to buy things we couldn’t afford on our own, increasing the overall productivity of the economy. But it also has a dark side: debt. This is where interest rates come in.

With low rates, the debt cycles can become more volatile because people think that they’ll be able to pay back their debts quickly and easily. This encourages more debt. So, when the debt cycle heats up, the Fed raises rates to slow down this enthusiasm toward what Dalio calls a “beautiful deleveraging.” That brings us to where we are now.

What happens next?

The trick with removing debt, or leverage, from the economy, however, is that increasing interest rates makes it harder for people, businesses, and ministries to borrow money. Imagine if your church building’s mortgage interest rate went from 3.5 percent to 5.5 percent in a matter of months — then your church’s debt becomes more of a problem. The same goes for corporations — and even governments. One investment manager recently said that each 1 percent increase in interest rates increases the annual federal debt service costs by $200 to $300 billion. It can also increase the debt burden that poorer countries face.

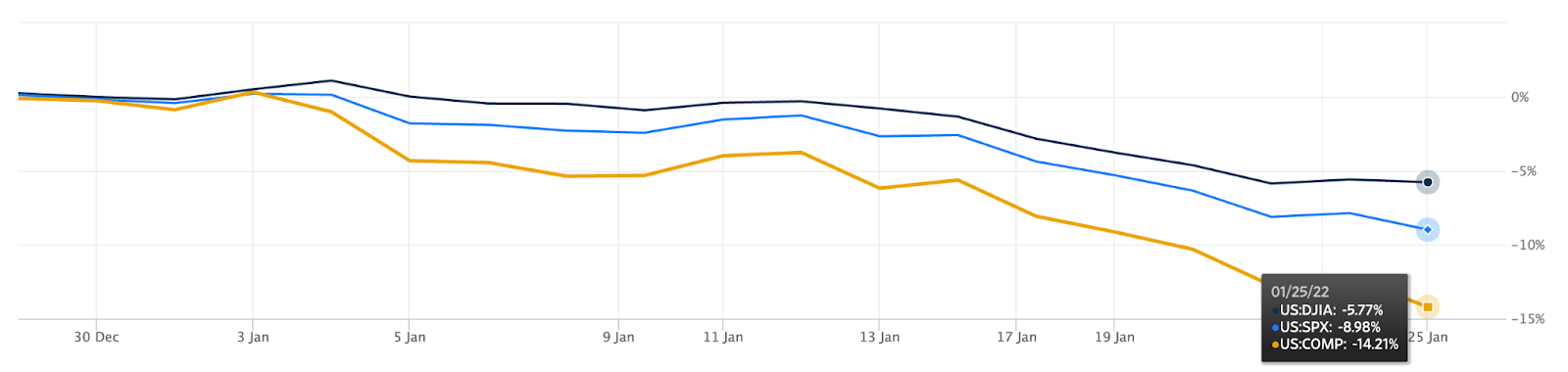

This rate increase is partly why the stock market has taken a nosedive lately. Investors think interest rates will rise, which lowers the value of debt-ridden and high-growth companies, like tech stocks. The Nasdaq, composed of many big tech companies, is down more than 14 percent, just over the last month.

At any rate, many analysts believe the Fed will increase rates this year, perhaps as many as three or four times. Again, this will slow down borrowing, but much like the high interest rates we saw in the 1980s, it may end up hurting many individuals and businesses by increasing their debt burdens and cutting off credit. No credit, no growth. The last time the Fed hiked rates, the economy went into a recession and unemployment soared.