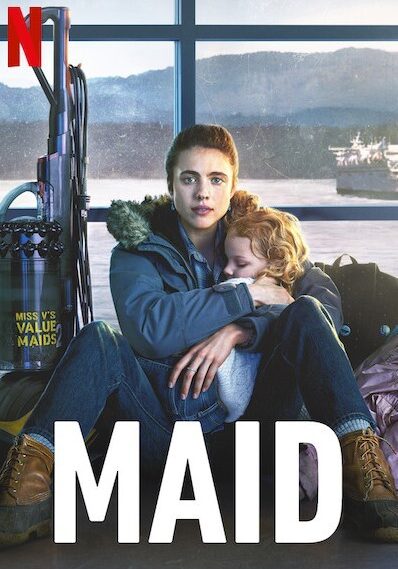

When introduced to a new show or storyline, you’re probably looking for a few main archetypes. A heroine. A love interest. A villain, plot line, and resolution. But what if one of the characters on stage was not, in fact, a person, but a principle? What if economics was the main antagonist of our series, playing a front and center role in the battle the heroine must face?

The antagonist is just that in Netflix’s new show Maid, starring Margaret Qualley (Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood) as the show’s protagonist, based on the 2019 memoir by Stephanie Land.

The story begins with Alex, a young mom, and her young child leaving a run-down home in the middle of the night. As she speeds away from her daughter’s half-asleep, mumbling father, the gas tank in her getaway car reads empty. As she pulls into the nearest gas station (far enough away to bring her daughter and herself to safety), the audience immediately understands the role economics will play in the season to come. At the top right-hand corner of the screen, $18.00 appears in white font. As the gas tank slowly fills up, Alex’s cash on hand slowly shrinks, until the total reads $12.35.

Based on Land’s 2019 memoir, Maid: Hard Work, Low Pay, and a Mother’s Will to Survive, the show gives what many critics (NPR, Slate, to name a few) call an “unflinching look” at a single, young woman’s story through generational abuse, trauma, and a never-ending series of dilemmas awaiting her path as she tries to lift herself out from under the burden of poverty.

Cut to our heroine’s next task: to find safe, affordable housing.

The morning after Alex’s escape, she speaks to a social worker who inquires about her health, her housing, and her employment. After a few curt questions and some legal-ese jargon, Alex finds out her options for affordable health care are next to none (without proof of employment, that is). In order to get a job, though, Alex retorts, she would need daycare. And to afford daycare, she would need money. An all-too-familiar catch-22.

The series delves into the social, psychological, and financial challenges of those in vulnerable positions, doing what they can, with what they have, to lift themselves out of poverty. This show raises the question, What does it look like when a person is doing everything right? If she is doing everything she can, why can’t she catch up?

In this story, Alex leaves her abusive home before a domestic incident occurs, noticing the tell-tale signs of threatening commands and broken dishes as a sign to get help. She leverages her family resources to the best of her ability. She inquires into all the right social services that are designed to help in her area. She’s the good, hardworking laborer that every employer wants.

And yet.

The means to lift oneself out of a deep well of poverty still requires a rope and pulley. And that rope, more often than not, is more expensive than most people expect.

Maid is a series that deeply touches on the rollercoaster of financial strain, emotional toll, social hardship, and the cycles of hope, burn out, and restoration the impoverished often experience.

As we follow Alex’s journey, economics is largely at play. Not only in the status of the right-hand corner piggy bank. But in access to knowledge. Legal help. Psychological freedom. Economics, as it does to most TV shows and movies, pervades all facets of life.

This system of roundabouts offers those in poverty not the help they need, but extraordinary efforts (and not to mention headaches) to actually hoist themselves out of desperation and onto any semblance of solid ground. It’s a merry-go-round, of sorts, to find yourself back in the same old places, even after jumping through many, many new hoops.

This isn’t only true to Alex’s story, though. The pain we feel for the on-screen protagonist should also translate to the way we feel toward the impoverished, the abused, and the vulnerable in our own communities.

In 2020, 18.7 percent of white, non-Hispanic families with a single mother were living below the poverty level in the United States, with an increasing percentage margin for those in other demographics. It’s reported that 1 in 3 women (and 1 in 4 men) in the U.S. have experienced some form of physical violence by an intimate partner, and it’s predicted that victims of intimate partner violence lose a total of 8.0 million days of paid work each year. These statistics don’t just have social and psychological implications, but economic ones, too. Between 21 and 60 percent of victims of intimate partner violence lose their jobs due to reasons stemming from the abuse, debunking the myth that lifting oneself out of poverty is based solely on work ethic and nothing else.

I’ll be honest, when I was first asked to review Maid, it took me a few weeks to finish. Not because the storytelling wasn’t stellar; it was. And not because the acting wasn’t superb; every actor rose to the occasion. But after a few episodes of watching a young woman (my own age) dip and re-dip into cycles of poverty, mental health crises, and abuse, it was too hard to want to watch.

That’s the whole point. The viewer’s challenge to get through a sobering few episodes of fictional toil is supposed to hurt. It’s supposed to be hard. And it’s supposed to give us empathy to connect us to the real people, with real problems in our lives, that need our real reaction.

As Christians, it should give us enough holy dissonance to do something different — to leverage our connections, resources, and economic standing to disrupt cyclical poverty, and to utilize empathy as a means of seeing and saving the “least of these” from exploitative processes. This holy mixture of hurt and hope is the economic sweet spot to which God calls us.