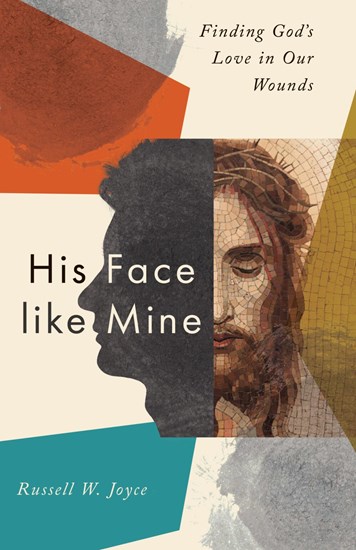

His Face Like Mine: Finding God’s Love in Our Wounds

By Russell W. Joyce

(IVP 2024)

“Scars are the signs that everything we say about Jesus is true. Scars are the portals to experiencing the living God. They must be on full display in our lives and our churches once again.”

—Russell W. Joyce

Russell W. Joyce and his now wife, Anna, were just engaged, swooning over each other, and kissing. Suddenly, Anna pulled back. “Stop that,” she said. Joyce had no idea what she was talking about. Anna explained: When she tried to kiss the left side of his face, Joyce would adjust, moving to kiss her lips or start telling her how much he loved her.

Joyce says he hadn’t realized the habit, but he knew its origin. So did Anna.

Joyce was born with a rare craniofacial disorder called Goldenhar syndrome. The left side of his face, as well as some other parts of his body, were underdeveloped or, as in the case of his cheekbone, missing altogether. After more surgeries than he could remember, Joyce writes, he still has “a sunken left cheek … a bumpy, angular, reconstructed ear,” and a scar from mouth to ear.

When Anna kissed his scars, Joyce felt a vulnerability so extreme that he thought he was going to faint. As the shock and rage inside him began to melt away, it was replaced with grief so deep that it felt like a death.

“I had been chosen and loved throughout my life by my parents and brothers,” Joyce writes in his new book, His Face Like Mine. “But the narrative I believed was that if my family had been honest, they would not have chosen me, not loved me, not kissed me. In my mind, they were overlooking my wounds because they were compelled to do so. … Anna wasn’t bound to me by blood. If she wanted to love me, it was her free choice. … In that space of utter brokenness, I was deemed worthy of her love. And I encountered God like never before.”

Joyce recently spoke with Common Good about what it looks like to be loved inside of our brokenness and not in spite of it and about the Savior who still has scars.

You write that God “isn’t avoiding our sinful wounds. Rather, he is charging headlong into the most painful elements of groaning creation.” How has this shift in perspective changed how you see your faith and yourself?

It’s liberated me! As grace is supposed to, it’s set me free. I think that was one of the more tragic realizations while working out the material of this book. I found that there were some layers of my human condition I had no trouble believing God loved and had embodied in Jesus Christ. But there were other, much deeper, more wounded, vulnerable, and fragile layers of my human condition — and many of them my sin-borne wounds — which I had never imagined in my wildest dreams God would have wanted to draw near to, love, or heal.

When that reality dawned on me, that Jesus longed to join me in the worst parts of me not just to save me, but because he loved me and wanted to be with me in every part of my being, that was when I felt like I had a second conversion. I understood the psalmist when he wrote about the joy of my salvation. I felt that in my belly like never before. It made God more unsafe than I had ever imagined and it made the power of his love in Jesus more beautiful and satisfying than I had ever experienced.

It also catalyzed my soul toward evangelism. I truly want people to know that they can stop hiding, that they don’t need to be afraid. Because the living God is not avoiding their worst. He is longing to meet them there with a love they don’t deserve but will nonetheless receive. This all because Jesus loves them — not the person they think they should be but the real person that they are, broken, wounded, and vulnerable. Jesus loves that one. This is insanely good news.

Why do you think Christians often hold back from offering up their full selves to the love of God and others?

Fear. And a legitimate fear, for this is our experience in the world. When we offer up our wounds and vulnerabilities to others we’re often met with judgment, exploitation, and further pain. We learn that there are some layers to our souls that the world simply cannot handle. Then we hear this gospel of a God who loves the sinner and hates the sin and we think, Well, any part of me that’s been stained and wounded by sin, God must hate.

So we present the unstained parts of us to him thinking those are the only parts he wants. We fail to realize that when Jesus went to the cross he went there not just to break the power of sin but to join the sinner because he loves the sinner, even at the sinner’s worst, when he is receiving the wounded wages of his sin. That is miraculous. But it is fear that holds us back. As we’re told, perfect love drives out fear. When we truly consider the perfect love of Jesus on the cross, our fear begins to be broken, dispelled, and replaced.

How do we “empty the cross of its power” when we refuse to allow people to see our whole, vulnerable selves?

The cross shows a God who joins humanity in its worst because he loves us. The empty tomb shows a God whose love is stronger than our worst. If we cannot or will not show others our whole, vulnerable selves, then we deny that the cross is strong enough to heal our worst. It is only by boasting in our scars, which were once wounds, that we give others a glimpse of the healing power that they so long for in their own lives.

It is imperative we remember Jesus came out of the tomb with scars. These marks were wounds of shame on Friday but signs of glory and God’s strength on Sunday. If we don’t boast in our scars, we must wonder if our wounds are fully healed? And if our wounds aren’t fully healed, we must ask if we’ve met Jesus completely at the cross? And if we haven’t met him there in those wounded places, then his powerful love has not healed us there. But if his love has healed us there, then we will bear scars on our souls as signs of glory for they testify to Jesus’ power. And if these scars are signs of glory, then we must lift them high to the world, as Jesus showed his scars to his disciples, as proof that the God we worship, adore, and trust is exactly who Jesus said he was.

How do the sacraments embody the church’s corporate scars?

Augustine described the sacraments as outward expressions of an inward grace. They are external marks that testify to an inner healing. In other words, they’re scars. They make visible to the body of Christ where we once were wounded but now are no longer. So, for example, when we take the Eucharist as a church body, we are all remembering our soul’s deep wounds and how Jesus’ love met us there through his sacrifice and healed us. We are, in effect, lifting high our soul’s scars to one another and to the world, which means we’re lifting high Jesus’ scars, too.

This is why the sacraments are so important to the life of the church. They are the corporate ways we remind ourselves of the power of God’s grace by embodying our weakness before one another. From an outsider’s perspective, how odd it must seem for someone to submit to baptism, to go underwater and in so doing confess that they need their old life to die, their wounds to be completely filled by God’s love, and receive a new life with Jesus Christ as their animating center. The sacraments point to healed wounds in a human soul. It’s foolishness to the world, and yet, for us, it is the power of God.

How might Christians who tend to only show their ‘good side’ begin to share who they are more fully?

Start small. In the Garden of Gethsemane, Jesus was arguably at his most vulnerable. Luke’s gospel said he was so overcome by sorrow he sweated blood. He could not hide his soul’s weakness and need. And yet it was still his nature to bring his three closest friends around him to pray with him. But notice, he didn’t invite the whole 12. He only let James, John, and Peter see that level of vulnerability. So ask God if there is one or two people in your life with whom you might take a step and trust them with your real, vulnerable self.

The sacrament of confession is a great place to begin. Confession does not mean it has to be the deepest, darkest things, either. It’s simply a posture of revealing oneself to another for the purpose of mutual prayer, encouragement, repentance, and healing. To simply let things out of the darkness and into the light, with another brother or sister in Christ who can remind you in those places of the good news of Jesus’ love, is a great way to begin to show every part of your soul, even the parts you don’t want to reveal. Do that enough times and it becomes a habit. Continue to practice it and it becomes a new identity and a song in your heart telling of the greatness of Jesus.

Many of Common Good’s readers are pastors or ministry leaders. What would you like them to know about scars, vulnerability, and the God who kisses our wounds?

Gregory Nazianzus famously said, “That which has not been assumed has not been healed.” “Assume” in this context means to identify with or to embody. The gospel reveals a God who has identified with every part of our fallen condition. Though he is without sin, he embodied the consequences of sin and bore them unto death to be with us. When he emerged from the grave, he emerged with scars testifying to the power of God’s love to triumph over sin and death and bring healing to our sinful and wounded souls. We can only know ourselves fully healed if we have allowed Jesus to fully embody and identify with our woundedness and turn it into scars, and then, we must boast in these scars. We must create communities where it is normative for our people to bear witness to the love of God found in their scars for this will create safety and a compelling vision for others to stop hiding their own wounds and bring them to the lips of Christ.

It’s not that we shouldn’t bring our strengths to the body of Christ. Of course we should. It’s rather that it should be clear to all that our center point is not our strength but our collective weakness. All resurrection power emerges from death. And if we try to bring strength and power that hasn’t passed through the refining fires of death, then it is not a strength borne from Jesus’ love. Scars are the signs that everything we say about Jesus is true. Scars are the portals to experiencing the living God. They must be on full display in our lives and our churches once again. And — at least in a Western context that privileges strength, conquest, and control — a people who gather around scars are a subversive counter-cultural witness.

This interview has been edited for clarity. His Face Like Mine: Finding God’s Love in Our Wounds is available from IVP.