This article originally appeared in our monthly email issue. Subscribe for full access to Common Good print and digital reads now for just $25 per year.

A vital aspect of humankind’s stewardship of the created world is the essential work not only of tending things and making things but also of cultivating and creating culture.

Andy Crouch suggests Christians adopt a stewardship posture anchored in cultivation and creation, what he often refers to as “culture making.” The stewardship of culture making involves both cultivators and creators. Crouch describes cultivators as “people who tend and nourish what is best in human culture, who do the hard and painstaking work to preserve the best of what people before us have done.” Creators, he says, are “people who dare to think and do something that has never been thought or done before, something that makes the world more welcoming and thrilling and beautiful.” Crouch makes an important point. Humanity’s creative work is varied, broad and far reaching. We not only make things or fix things, but also we are actively involved in creating, cultivating and contributing to, human culture itself.

The Depth of Avodah

The language of work as cultivation and creation in Genesis 2:15 is embedded in the Hebrew word avodah, which is behind the English translation “to cultivate.” The Hebrew word avodah is translated in various ways in the Old Testament. It is rendered as “work,” “service,” or “craftsmanship” in many instances, yet other times it is translated as “worship.” Avodah is used to describe the back-breaking hard work of God’s covenant people making bricks as slaves in Egypt (Ex 1:14), the work of artisans building the tabernacle (Ex 35:24), and the fine craftsmanship of linen workers (1 Chron 4:21). Avodah also appears in the context of Solomon dedicating the temple. Solomon employs this word as he instructs the priests and Levites regarding their service in leading corporate worship and praise of the one true God (2 Chron 8:14). Whether it is making bricks, crafting fine linen, or leading others in corporate praise and worship, the Old Testament writers present a seamless understanding of work and worship.

Though there are distinct nuances to avodah, a common thread of meaning emerges where work, worship, and service are inextricably linked and intricately connected. The various usages of this Hebrew word found first in Genesis 2:15 tell us that God’s original design and desire is that our work and our worship would be a seamless way of living. Properly understood, our work is to be thoughtfully woven into the integral fabric of Christian vocation, for God designed and intended our work, our vocational calling, to be an act of God-honoring worship.

Work as Worship

So often we think of worship as something we do on Sunday and work as something we do on Monday. However, this dichotomy is not what God designed, nor what he desires for our lives. God designed work to have both a vertical and horizontal dimension. We work to the glory of God and for the furtherance of the common good. On Sunday we say we go to worship and on Monday we say we go to work, but our language reveals our foggy theological thinking. That our work has been designed by God to be an act of worship is often missed in the frenzied pace of a compartmentalized modern life.

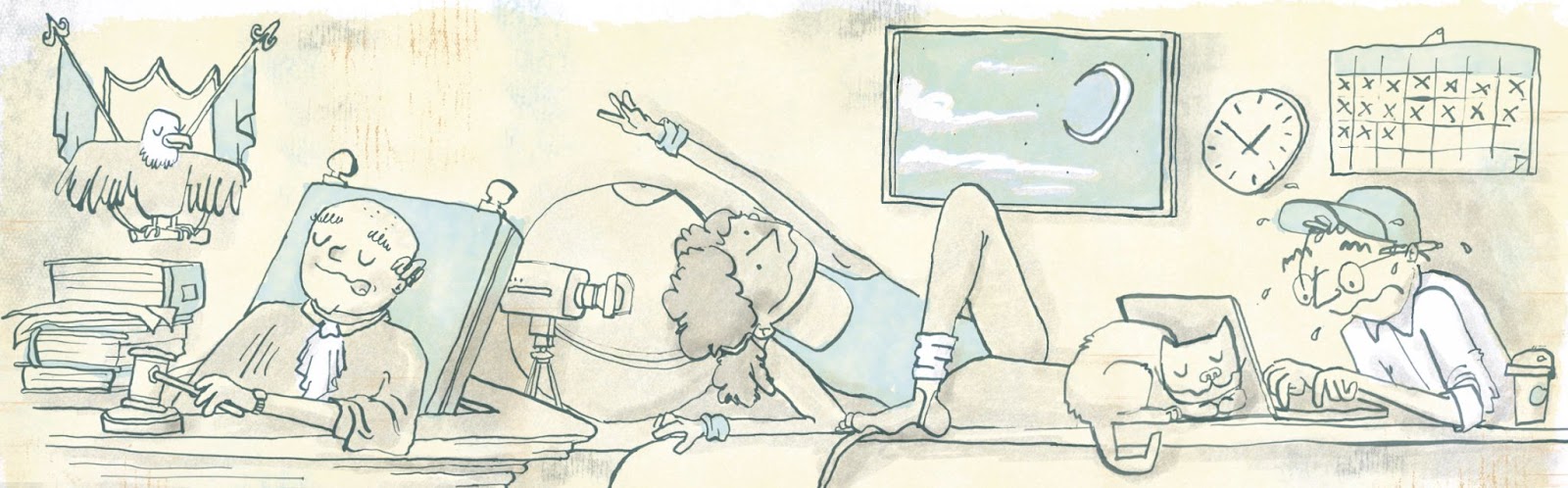

Dorothy Sayers, a contemporary of C. S. Lewis, gave a lot of thought to how followers of Christ who have embraced the gospel ought to see their work. She also spoke in a compelling way about how the church has so often dropped the ball when it comes to connecting our Sunday faith with Monday work. In a thoughtful essay simply titled “Why Work?” Sayers writes, “The Church’s approach to an intelligent carpenter is usually confined to [moral instruction and church attendance]. What the Church should be telling him is this: that the very first demand that his religion makes upon him is that he should make good tables. …”

Sayers is not saying that offering moral instruction and inspiring worship services is unimportant. Clearly this is an important stewardship of any gospel-preaching and Christ-honoring local church. But what we must not miss in her insightful words is the importance of the church in teaching each one of us that our work, whatever it is, is to be an act of worship. With remarkable insight, Sayers continues, “Let the church remember this: that every maker and worker is called to serve God in his profession or trade — not outside it. … The only Christian work is good work well done.”

So often we use the language of Christian work to refer exclusively to ecclesiastical, missionary, or parachurch callings, but this distorted understanding exposes our inadequate grasp of the transforming truths of Christian vocation. It is hard to imagine how our understanding of work and the quality of our work would change if we would truly embrace the truth that the only Christian work is good work well done. Sayers is not being novel; she is simply saying what the apostle Paul penned to the first-century church at Colossae: “Whatever you do, work heartily, as for the Lord and not for men, knowing that from the Lord you will receive the inheritance as your reward. You are serving the Lord Christ” (Col 3:23–24).

Rethinking Work

Worship as God designed it is seamless. It encompasses everything in life. All that we are, all that we say, all that we do is to be an act of worship before God. We were created with worship in mind. And if we were created with worship in mind, we were created with work in mind. This is part of the great impoverishment of our language and our structure.

Our English language equates work with compensation. The biblical framework does not dismiss that — we create value in our work that’s exchanged through an economic system. Yet understanding rightly the meaning of avodah, of work as it is introduced in Genesis, we understand the meaning of work and worship as God intended it — seamless. Both are true: Our work matters as it relates to economic life, and work is a primary way we glorify God.

We were created to contribute to God and his good world in and through the work of our hands, the value we add to others. Sometimes it’s compensated and sometimes it’s not. This means that no matter our physical condition, our mental condition, we contribute to God’s world, and that reality invites everyone into the work story.