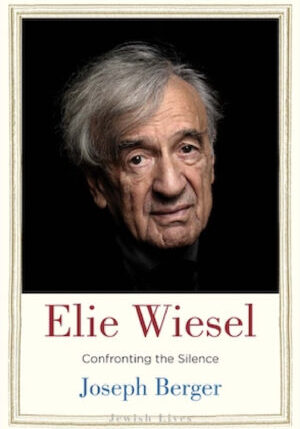

I especially recall two statements by Elie Wiesel. The first was “to forget the victims of the Holocaust is to kill them a second time.” The other, which became the motto of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., was “Remembering for the future.” These remarks portray the depth of purpose in Wiesel’s life’s work. Described as “messenger to mankind” by the Norwegian Nobel Committee, he received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986.

In Elie Wiesel: Confronting the Silence, a new volume of the Jewish Lives series, Joseph Berger, distinguished reporter and editor at the New York Times, presents an intimate, detailed portrait of the remarkable Wiesel, with whom I had the honor to work in the development of the U.S. Holocaust Museum.

Reconciliation at the core of the future

After publishing Night, Wiesel secured public attention both in Europe and in his new home in the U.S. The memoir recounted his experiences in the Nazi German concentration camps at Auschwitz and Buchenwald between the years 1944 and 1945. Determined to not forget the victims of the Holocaust, Wiesel decided to pursue the establishment of the Holocaust as a central reality in the consciousness of America and beyond. To remember “for the future” indeed.

I first met Wiesel when our own work intersected in 1974. I had already been involved in the developing Christian-Jewish dialogue ignited by the Catholic Church’s Vatican II Conciliar document Nostra Aetate, whose fourth chapter reversed the Church’s negative portrayal of Jews and Judaism, which had generated many concrete instances of antisemitism and led to the death of numerous Jews over the centuries of Christian political domination in Europe. To begin the process of establishing this memory of the public, Wiesel brought together a range of scholars and religious leaders, including myself, to implant Holocaust consciousness in educational circles and public life.

At New York City’s famed Cathedral of St. John Divine, the conference, which experienced some disruption from a group of protestors decrying American racism, attracted attention. I recall Wiesel, as conference chair, managing the unplanned protest rather adroitly, turning it into an example of the kind of social reconciliation that, in his mind, the Holocaust demanded. Reconciliation was thus launched by Wiesel as a core element of his post-Holocaust social vision. As Berger notes in his volume, Wiesel used this vision of reconciliation in his quest to heal political rifts with Germany and Poland.

For some reason Berger does not give this event the significance it deserves in his telling — the work here produced a significant volume of the conference papers titled Auschwitz: Beginning of a New Era?, edited by the holocaust studies pioneer scholar Eva Fleischner and led to the enhanced inclusion of the Holocaust narrative in educational materials at the secondary and university levels.

The pursuit of living memory

When President Jimmy Carter announced his intention to establish a national memorial to the victims of the Holocaust in Washington, D.C., he tasked Wiesel with leading the presidential commission, which then recommended the establishment of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council. That council was subsequently approved by the U.S. Congress. I was appointed as an original member (but only after I wrote a letter to Wiesel clarifying my views on the Holocaust as a Polish American).

Serving on the original council with Wiesel, I came to see him as a prophet and visionary, committed not only to the perpetual remembrance of the victims of the Holocaust — but also to the ongoing pursuit of justice — visions made reality by the work he led. The council’s two priorities were the erection of a national Holocaust museum in Washington, D.C., and the creation of a day of remembrance in the U.S. International Holocaust Remembrance Day is observed annually on January 27, the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau. The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum opened its doors in 1993.

For Wiesel, the Holocaust had to become a “living memory.” He saw forgetting the Holocaust as enabling the normalization of injustice and mass human degradation. So the council made the recommendation, at the suggestion of longtime Jewish activist Hayim Bookbinder, an ongoing Committee on Conscience, which would mandate the U.S. government make public forms of genocide and near-genocide in the post-Holocaust era. The Committee on Conscience is now a standing committee at the museum, which has become a unique moral voice on the Washington political scene.

Wiesel’s living legacy

For me, the most profound example of Wiesel’s moral sensitivity and courage came during the Bitburg Controversy in 1985. President Ronald Reagan planned to visit the Bitburg Cemetery in Germany, which included the graves Nazi soldiers. Several of us on the council gathered in his office for an informal discussion of his options, particularly his response to Reagan’s decision. He was clearly leaning towards resigning, in protest, from his role as council chair. But after leading us through an extended process of moral discernment he decided to stay. His subsequent address to the president was courageous and critical, arguably the central address of his life. “That place, Mr. President, is not your place,” Wiesel said. “Your place is with the victims of the SS.”

Wiesel left us a rich and powerful moral legacy that can and must serve as a major resource for moral reflection in our day. We owe a debt of gratitude to Berger for bringing us into intimate contact with the prophetic, and sometimes stubborn, Wiesel.

Berger covers Wiesel’s personal history from his Hasidic childhood in Sighet, in what is now Romanian territory near Hungary, and goes beyond Wiesel’s public involvement, not missing a moving portrayal of his wife, Marion, and his son, Elisha. The family celebration of Shabbat was sacred time for Wiesel, something he almost never missed. Yet, as Berger indicates, Wiesel struggled regarding his belief in a powerful God in light of the Holocaust, a central theme in his reflections in Night as well. But he was certain about the need for human responsibility, and he continually made the need clear. When challenged at a conference at Northwestern University with the words, “Professor Wiesel, how can you continue to believe in God?” Wiesel asked in response, “How can you believe in man?”