Start Here

Read these works side by side:

On Civil Disobedience

“Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” Martin Luther King Jr.

Apology, Plato

On Education and Freedom

The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (chapters 6 and 7), Frederick Douglass

“Allegory of the Cave” (in Republic), Plato

On Liberty and the American Revolution

“His Excellency, General Washington”, Phillis Wheatley

Wheatley’s letter exchange with George Washington, available at the National Archive online.

On Slavery and Natural Rights

Second Treatise of Government, John Locke

The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Olaudah Equiano

On the surface, we were incompatible in so many ways. I am a Black professor of sociology, conservative theologically but more progressive politically than the mothers I was with. Our life experiences could not have been more opposed, and I am certain our experiences of race in America were immeasurably different. But a year later, after our family had moved across the country, one of the mothers from this, my former homeschool group, reached out to me to request access to my reading list, discussion questions, and lectures on the Black intellectual tradition.

I was amazed. She was putting together a reading group comprised of Louisiana homeschool moms who were making a deliberate effort — outside of anything they needed to do in their busy lives — to have their children, and themselves, wrestle with the question of how to position themselves with respect to the past. Of course, this question is complicated.

In the 19th century, the search for answers was taken up by emancipated Black Americans. We see this in the opposed thinking of two great writers of the Black intellectual tradition: Alexander Crummel and Frederick Douglass. With respect to slavery, these two thinkers held differing opinions.

In “The Need for New Ideas and New Aims,” Crummel writes, “The morbid, absorbing, and abiding recollection of [slavery] — what is it but the continuance of that same condition, in memory and dark imagination?” In contrast, Douglass writes in “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”: “America is false to the past, false to the present, and solemnly binds herself to be false to the future.” Crummel urges Black Americans not to dwell on the past of slavery, but rather to press forward lest we be sunk into the worst depths of “memory and dark imagination.” Douglass, on the other hand vehemently disagreed, calling on Americans to remember always.

Today, we are still at war with one another. Our most recent iteration of this debate was touched off by the appearance of the New York Times’ 1619 project in the fall of 2019. The lead essay by Nikole Hannah-Jones threw down the historical gauntlet, declaring: “Our democracy’s founding ideals were false when they were written. Black Americans have fought to make them true.” The backlash was certain and swift. A group of prominent Black intellectuals created the 1776 Unites website and curriculum, emphasizing laudable histories of Black excellence overcoming adversity. President Trump’s 1776 Commission produced a counter declaration to the Hannah-Jones project, writing: “In the course of human events there have always been those who deny or reject human freedom, but Americans will never falter in defending the fundamental truths of human liberty proclaimed on July 4, 1776. We will — we must — always hold these truths.”

Are we fated to battle over these polarized positions or is there another way — a way that could help us to move forward productively rather than toward each other’s metaphorical (or literal!) throats? I believe there is another way, and that way, as Anika Prather and I argue, is via reading and reflecting on great books.

These are beautiful, complex books that include classics like Homer’s Odyssey and Plato’s Republic; the epic poetry of Dante; brooding novels like those of the Bronte sisters; and powerful, soulful meditations on justice such as we find in Douglass and W.E.B. DuBois, among many others. We put forward the somewhat counter-intuitive proposal that it is possible to build a bridge that connects us across enduring social and political differences — and that bridge is paved with classic and canonical literature that explores great ideas and points us toward the pursuit of truth, goodness, and beauty. And though the times are challenging, we are graced to live when there are more ways than ever to read and engage with these great works — everything from formal university study to free and low-cost great books seminars through organizations like the Albertus Magnus Institute and the Catherine Project.

But how could the reading of the often-maligned “dead white men” lead to such an outcome? The first step is recognizing that an education rooted in classic and canonical texts is not required, by definition, to lack diverse voices. In fact, the proof of the bridge-building capacity of a classical education lies in studying the writing and lives of Black intellectuals across the centuries who have defended their freedom, dignity, and political rights precisely by appealing to classic writings and ideas.

Socrates — via Plato — has been one of the most enduring favorites among Black writers whose focus is on freedom of both the mind and body. The “Allegory of the Cave,” the famous depiction from Plato’s Republic, shows up in various ways in writers as diverse as Douglass, DuBois, and Huey P. Newton. And documents of the American founding themselves are rooted in the thought of Cicero, Locke, and Montesquieu, among others, and were plumbed for their ideals of equality and justice over and over again. The Judeo-Christian scriptures have sustained the spirits and fired the visions of writers from Phillis Wheatley in the 18th century to Martin Luther King Jr. in the 20th.

Still, this is only one part of the healing story. The second part involves what happens when people from diverse backgrounds come together to read and reflect on these works. And this brings us back to my fellow homeschool moms in Louisiana.

After they had decided to create the Black intellectual tradition reading group, they invited me for a visit. I joined a generous feast with great conversation where they served me beef raised on the family farm, deer butchered nearby, and other dishes representative of the rich Louisiana cuisine I heartily miss in Virginia. We prayed and ate together and discussed the seminar they would soon undertake with this material. Since then, the leader has sent updates, acknowledging how hard it was to read some of the material but also affirming that she would be requiring her high school-aged son to do the course for his next academic year.

This response is not unusual. I have had many heartfelt conversations with educators who differ greatly from me in race and political conviction, who nevertheless are eager to learn this tradition and to grapple with our country’s difficult past. Engaging the classics in this light is not a panacea for all that ails us, but its bridge-building capacity is not in doubt. Reading these great books, formally or otherwise, that centers founding documents and a diverse group of great writers placed into conversation with each other provides a foundation that allows us to couple honesty and grace with respect to our contentious and complex past.

Take and read

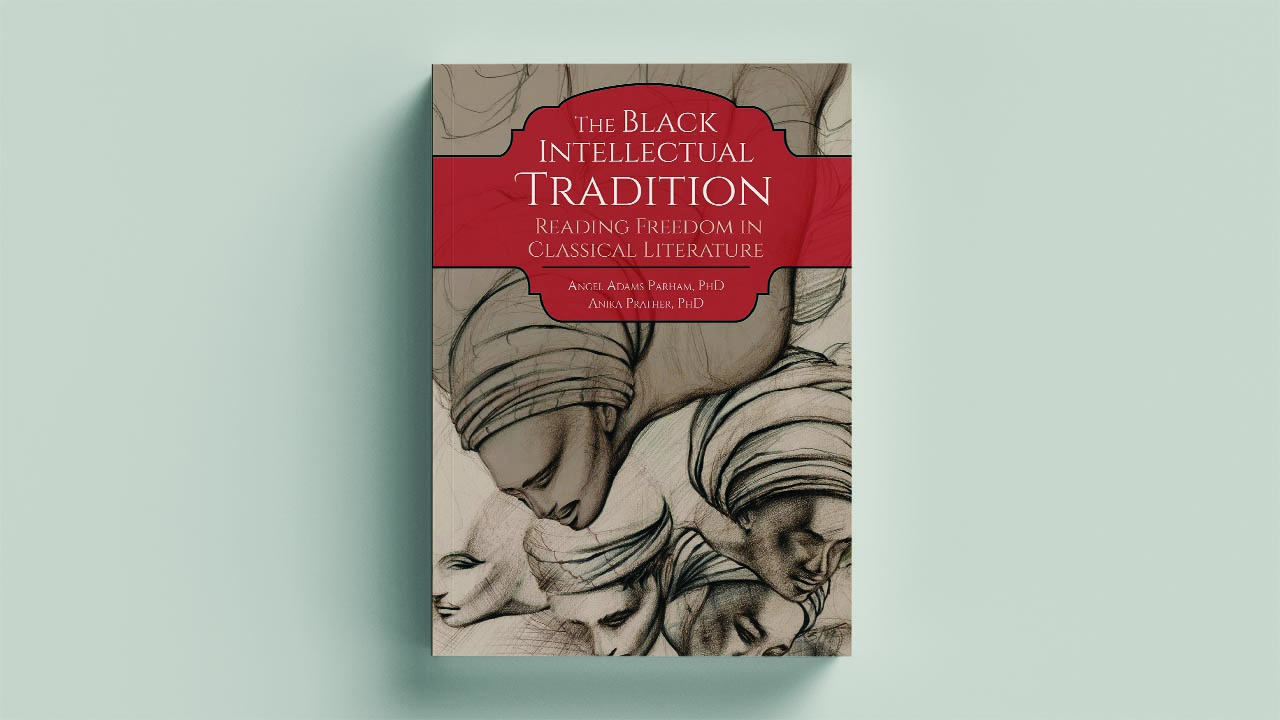

The Black Intellectual Tradition:

Reading Freedom in Classical Literature

(Classical Academic Press, 2022)

By Anika Prather and Angel Adams Parham